created 2025-07-03, & modified, =this.modified

tags:y2025surrealism

rel: Surrealist Objects

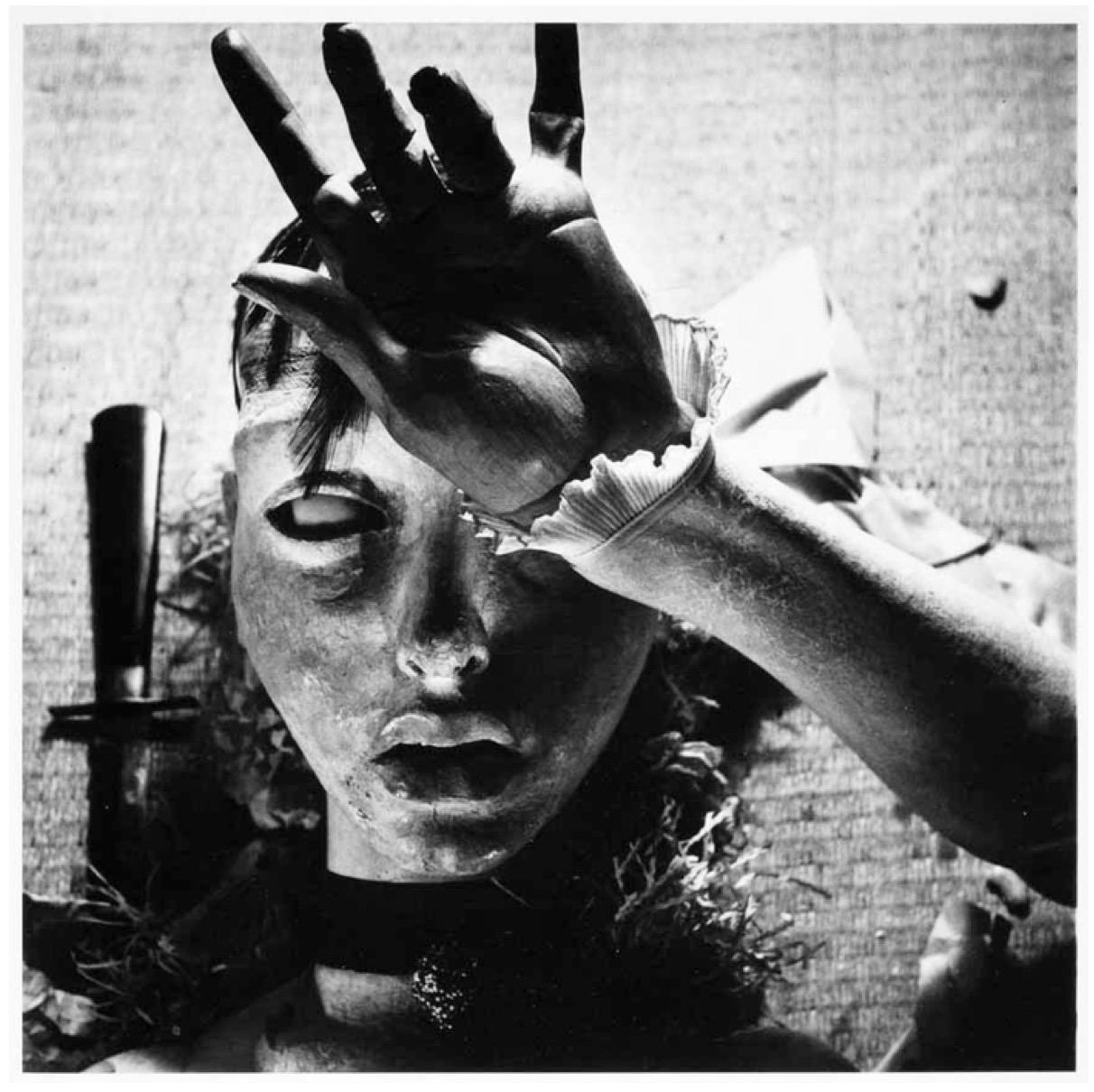

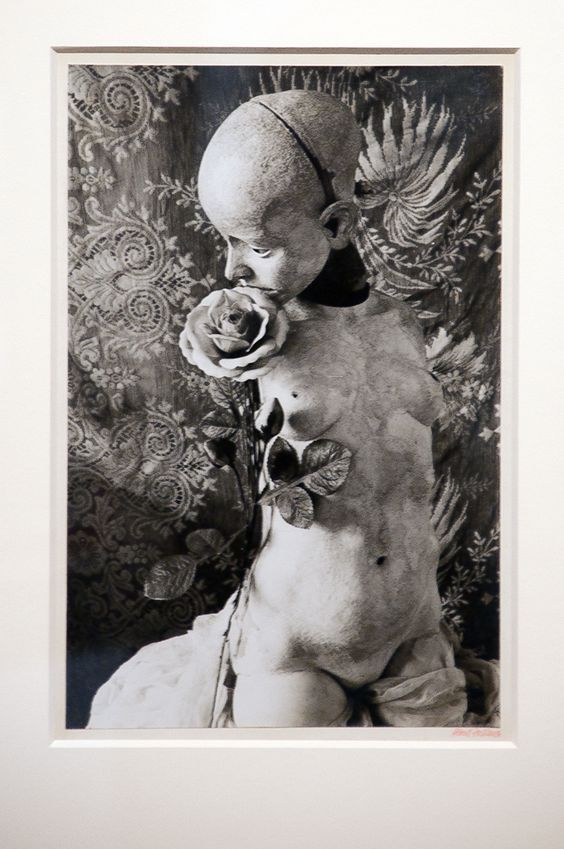

Hans Bellmer’s Die Puppe (The Doll) photographic series is perhaps one of the most bizarre works to come out of the surrealist group in the early-to-mid twentieth century. Of every peculiar aspect of the photographs, perhaps the most striking is his treatment of vision. Bellmer always poses his dolls, which he disassembles and reassembles into various unnatural shape, so they face away from his camera. Sometimes he removes their eyes altogether.

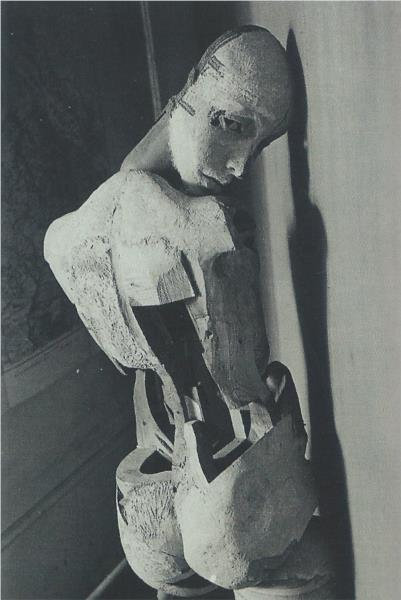

In 1933, Bellmer and his younger brother, Fritz, constructed his first doll, which Sue Taylor describes well as “a molded torso made of flax fiber, glue, and plaster; a masklike head of the same material with glass eyes and a long, unkempt wig; and a pair of legs made from broomsticks or dowel rods” made to resemble an adolescent girl.

Often, the eyes are left separate from the face and lie next to the body, like marbles.

Bellmer

And didn’t the doll, which lived solely through the thoughts projected onto it, and which despite its unlimited pliancy could be maddeningly stand-offish, didn’t the very creation of its dollishness contain the desire and intensity sought in it by the imagination? Didn’t it amount to the final triumph over those young girls—with their wide eyes and averted looks—when a conscious gaze plundered its charms, when aggressive fingers searching for something malleable allowed the distillates of mind and senses slowly to take form, limb by limb?

For Livia Monnet, who focuses on the idea of permutation in Bellmer’s dolls, this flexibility is essential to Bellmer’s control over the female body, making what she calls “a plastic anagram” that one can dislocate and constantly rearrange.

1816 Der Sandmann

rel:The Sandman The short story follows a young man who finds himself enamored with a beautiful woman, Olimpia, who he later discovers is a doll and whose creator is his father’s murderer and the source of his childhood trauma. The murderer, Coppelius, claims ownership of Olimpia over the man who made her internal clockwork, because Coppelius specifically made her eyes; seeing her without her eyes leads the protagonist to understand his lover was never truly alive. As a result, he enters a fit of madness.

Each assembly of Bellmer’s first doll resembles a feminine doll in pieces, but many iterations of his second, ball-joint doll share more qualities with a spider or a pile of bubbles than a girl; its disfiguration becomes more central. Fragmented images of women are common in surrealist art.

In participating in the mass market economy, woman both relies on machines and becomes part of a machine. Hal Foster notes in Compulsive Beauty how definitions of female and mechanical became intertwined during the Industrial Revolution. Foster claims that:

A…patriarchal apprehension greets the commodity, indeed mass culture generally, throughout the nineteenth century, both of which are also associated with women. This gendering is not fixed in surrealism…but certainly ambivalence regarding both machine and commodity is figured in this way: in terms of feminine allure and threat, of the woman as erotic and castrative, even deadly.

This fear or sense of discomfort likely arises from the uncanny perception that a feminine, therefore sensual and Dionysian, force is so closely connected to powerful, yet unfeeling objects.