created 2025-02-20, & modified, =this.modified

Why I am reading

What are the best tools we have to map reality?

What are the limits of what I can say?

We create our worlds by the language we use.

John Gluck: “If you must sanitize the language that is used to describe the procedures in regular use,” Gluck wrote, “you have entered morally perilous territory.”

Just as language cannot create physical reality, it cannot merely reflect physical reality as it is. It always imposes a doubly-subjective vision, consisting of the views encoded in the language being spoken and the view of the speaker who chooses the words being used. Language is shaped by our subjective, purpose-calibrated view of reality. And in turn, our view of reality is shaped by language.

Words do not give us direct control, magical or otherwise, over brute reality. Researchers of mind have long known that human rationality is not an ideal tool for truth seeking.

Human reason evolved because it is a social tool, not a tool for classical logic. Reason evolved for convincing and persuading other people, winning arguments with other people, defending and justifying actions and decisions to other people. These functions may be achieved regardless of whether the content of a proposition is true.

Truth becomes a collateral victim of human sociality.

Perception is private, language is public.

Using language to simplify reality is not only the business of ordinary social sense making; it is also important in scientific progress.

Constrained Diversity - All languages capture only a tiny part of reality.

Mapped by Language

Coordinating around Reality

One sense of coordination - adopting a common stance toward a landmark, a shared focus or attention. Many species engage in this, but we humans have remarkable capacity to use such landmarks as cognitive tools for achieving coordination even in the absence of communication, in a kind of virtual mind reading.

#map

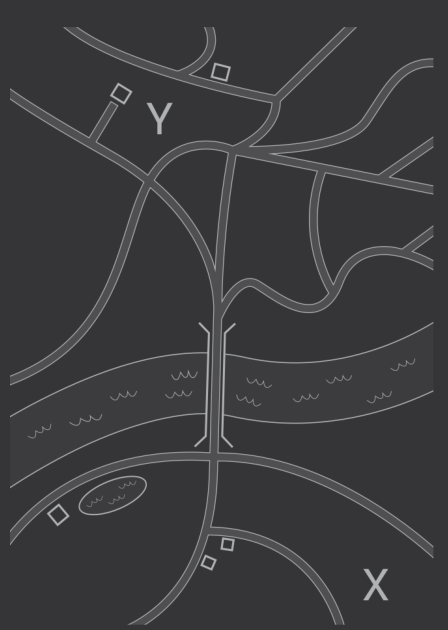

Schelling’s map - two parachutists are given a map. They cannot communicate but must find each other by going to where the think the other will go, each knowing the other has the same map.

Most people would meet at the bridge. We appear to be able to achieve ad hoc coordination of this kind without communication.

Most people would meet at the bridge. We appear to be able to achieve ad hoc coordination of this kind without communication.

Another sense of coordination: when we use language in interaction, we draw on landmarks to infer common solutions to the problem of converging in thought and action. Language is a portable device for constructing such landmarks at will.

NOTE

This is similar to “Natural Lines of Drift.”

Natural lines of drift are those paths across terrain that are the most likely to be used when going from one place to another. These paths are paths of least resistance: those that offer the greatest ease while taking into account obstacles (e.g. rivers, cliffs, dense unbroken woodland, etc.) and modes of transit (e.g. pedestrian, automobile, horses.). Common endpoints or fixed points may include water sources, food sources, and obstacle passages such as fords or bridges.

At every step, we enhance our individual agency using person-extending technologies from levers and wedges to bicycles and smartphones. These technologies are interfaces that translate or transform our actions beyond what our bodies alone could do.

Language is the most flexible, powerful, and all-pervasive agency-extending technology we have. Many would say that language is a way of conveying experience and ideas to other people, but it does not transfer the contents of what we have in mind. Rather, it invites people to imagine what we have in mind.

NOTE

You cannot communicate with them because their use of language is different. The “landmarks” are altered to not correspond correctly with the ones you mean?

Car analogy

Think of language like the interface that allows you to operate your car. We drive along, with near-zero effort, pressing pedals and buttons, turning wheels and levers. In ways that are mysterious to most of us, these actions control the inner workings of the car. With language, we control the inner workings of other people. Things are happening under the hood that few of us have any idea about. The interface of words hides most of the underlying reality that it operates on. But there’s a catch: when you control the device, the device controls you. You don’t just use the pedals and buttons to operate on another person. The same pedals and buttons are operating on you in return.

Two types of reality

- Brute reality - in the realm of natural causes - can be captured by language only in the most partial, subjective and fragmentary ways. It isn’t affected by whether we talk about it or by how we choose to describe it or frame in.

- Social reality - the realm of rights, duties, and institutions - cannot exist without language. Language can describe both, but the tools it uses to do so - essentially word meanings - are bits of social reality. The line between my property and my neighbor’s property has the meaning it has because linguistic acts have made it so, and we all agree to abide by those acts (which are, by the way, ultimately backed up by the state’s monopoly on force—back to brute reality).

Brute reality is unaffected by our norms.

Brute reality is “that which, when you stop believing in it, doesn’t go away.” Philip K Dick.

It’s difficult to overstate how poor language is at capturing brute reality, or at transferring the richness of people’s perception or experience.

Suppose I say to you, Jo drives a red car. Now, what if I ask you to do a painting of the car as you see it in your mind? Which exact shade of red do you choose? What sort of car is it? What if I asked you to pick out Jo’s car in a parking lot? Could you do it? Not likely if there were ten red cars of slightly different shades. Or suppose I describe Jo’s face. Would you be able to pick her out from a lineup of ten similar- looking people, based solely on my verbal description? Even assuming you are a skilled portrait artist, could you draw her face accurately from my words alone? Language provides nowhere near the required level of information for the task. And not only that, as we’ll see, language distracts us in various ways. It can divert our attention and mess with our memories.

Brute reality statement - “if I drop these potatoes they will fall” will remain true no matter what people believe. By contrast, a statement about social reality - “These potatoes belong to me” - is entirely dependent on people’s beliefs.

It is sometimes argued that brute reality is trumped by social power, that “facts” are illusory, as if anyone with power can decide what is true and what is not. But social power can only change social facts.

Niels Bohr, in the context of his famous debates with Einstein a century ago, stated: “There is no quantum world. This is only an abstract physical description. It is wrong to think that the task of physics is to find out how nature is. Physics concerns what we can say about nature.” rel:Expression

no-telepathy assumption “No mind can influence another except via mediating structure.” Ultimately, when we have learned a language, our minds have become “organized by structure created by other individuals.” We are all mutually implicated in the collective significance of our languages.

Schelling’s Game

Every living creature is in fact a sort of lock, whose wards and springs presuppose special forms of key. —William James (1884)

Another example of Schelling’s Game: Two players, given 100, otherwise nothing.

90% of people choose 50/50.

People coordinate around things that have some kind of prominence or conspicuousness.

Using language is itself highly practiced solutions to coordination game. Becoming highly practiced at using language means recognizing the prominent features that word meanings provide.

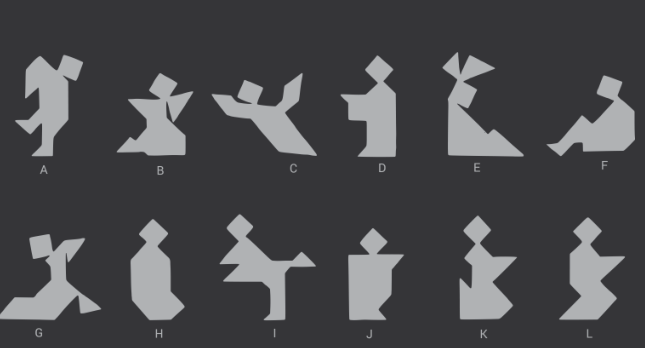

Tangram Study:

Two roles are given, director and matcher. The figures all evoke a human form and the order must be matched. Initially the descriptive language is convoluted.

All right, the next one looks like a person who’s ice skating, except they’re sticking two arms out in front.

Subsequent rounds and contextual convention is established:

Round 2. Um, the next one’s the person ice skating that has two arms? Round 3. The fourth one is the person ice skating, with two arms. Round 4. The next one’s the ice skater. Round 5. The fourth one’s the ice skater. Round 6. The ice skater.

In another example you are asked to read a paragraph. You provide a summary. Your paragraph is given to the next person, who is asked to write what they recall from your summary. Each round results in ever simplifying language.

21 distinguishable events become “she went to the supermarket.” rel:Future Reading Method

We are so fixed at the convention of simplicity that in fact, when we do mention them, this departure from the normal economy of expression signals to our addressee that we are adding this detail for a reason. rel:Ridiculously Explain

Language is not good for capturing and transmitting the details of reality. What it’s good for is providing landmarks we can coordinate around.

We can use language to update people on unseen realities. But this does not mean that our experiences are literally transferred to others simply to be downloaded and viewed or experienced.

Language and Nature

Words do not express thoughts very well. They always become a little different immediately after they are expressed, a little distorted, a little foolish. —Hermann Hesse (1922)

Venus has two names: Morning star, when it hangs in the east at sunrise and Evening star, when it hangs in the west after sunset.

Gottlob Frege gives the terms reference and sense. For example a half hour, versus thirty minutes. The reference of the expressions is identical. The sense is not the same, because of different modes of presentation.

Dan Slobin: Language evokes ideas: it does not represent them. Linguistic expression is thus not a straightforward map of consciousness or thought. It is a highly selective and conventionally schematic map.

When you use the word for something, there is not only a link between the word and the thing you are referring to, but also, and always, a link between you and the person you are talking to.

Walking and Running Study

People are placed on treadmills moving at various speeds. Researchers wanted to know if there is a sharp biomechanical break between the walking and running gait, labeled in all languages. They found variation across all languages, such as English having specific terms for locomotion such as stroll, saunter, jog and sprint. But the finding was that the distinction between walking and running was captured in all otherwise unrelated languages. It is evidence that languages can converge in how they name a piece of reality because they respect the structure of that piece of reality.

Languages have constrained diversity: they vary but only within the same narrow range.

Words capture only a tiny fraction of what we can distinguish with our senses. If you have an experience and you try to put it into words, much will be lost in the process. If the only information someone has about a scene is in the words you’ve used to describe it, that person will hardly be able to recover anything of what you have in mind, let alone the details of the scene itself.

Language doesn’t only strip away reality. It also distracts us and misleads us as to what we think is even there.

Priming and Overshadowing

If you are primed with a word related to the image you need to name, or especially if you see the word for the object itself, then you will be faster in naming the object when it appears.

Priming can also make us overconfident on what will come next.

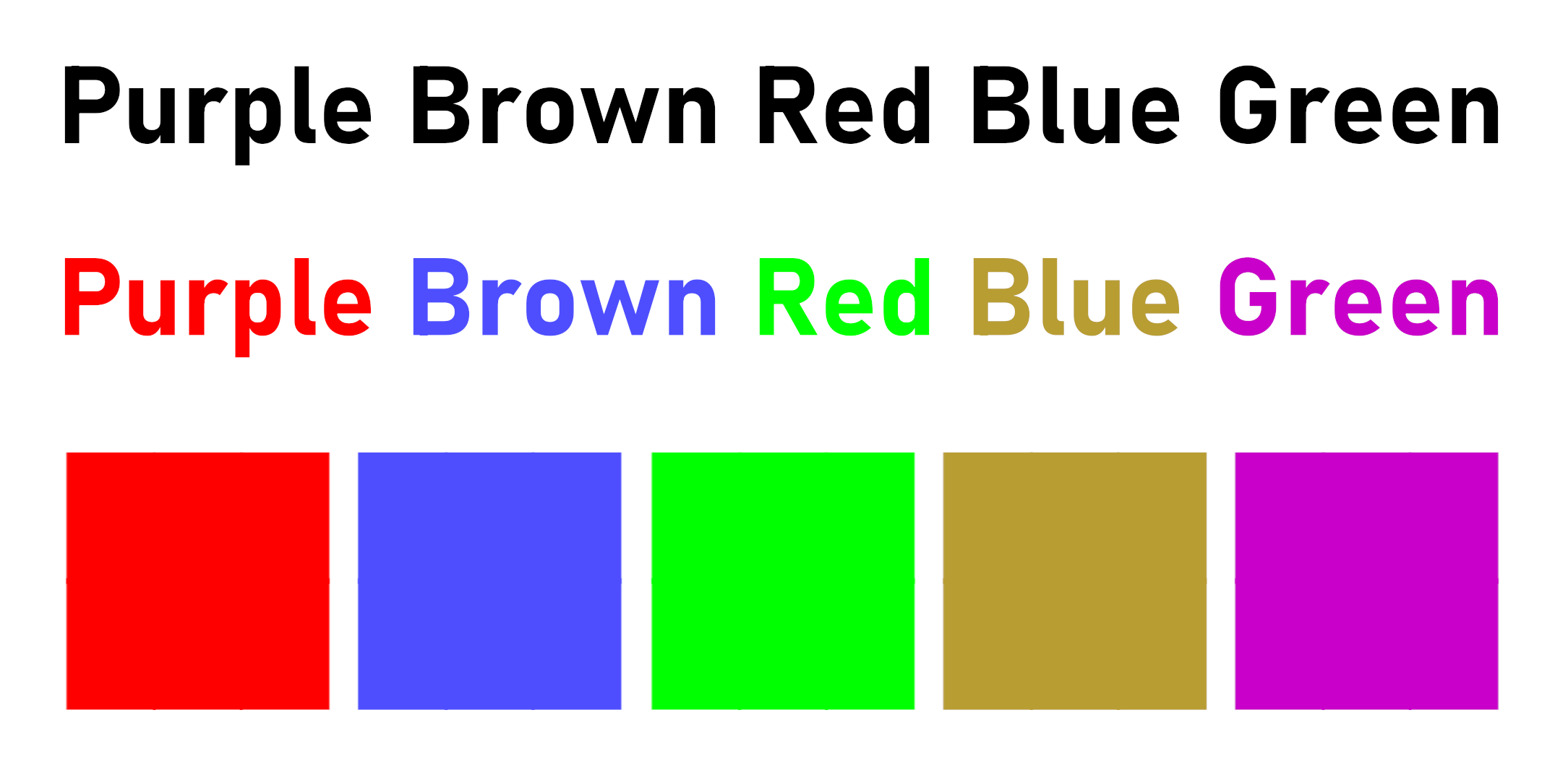

1930s by American psychologist John Ridley Stroop. The Stroop effect is a delay in reaction time between neutral and incongruent stimuli.

Semantic Priming - a way to bias people toward one or the other option using an indirect way of diverting their attention to one or another part of the image.

Language doesn’t just affect how fast we respond or the kinds of sentences we produce, as we’ve seen in these priming studies. Language can also affect our beliefs about what we think we’ve seen.

Freidrich Wulf showed a set of simple abstract line drawings. When people drew them from memory they would omit details and exaggerate others. People “normalized” the images to better resemble familiar shapes or objects.

Their descriptions would be “two triangles” “the letter W” or “mountains.”

These examples suggest that when people need to remember things, they can use their existing knowledge of familiar objects as a reference point.

In 2018, Christie’s auction house sold the world’s first AI-generated painting, created by a deep-learning algorithm trained on Renaissance masters. It sold for half a million dollars. Computational social scientist Ziv Epstein and colleagues found that people reasoned differently depending on the language used: when the algorithm was described as “a tool,” people attributed more credit to the person who trained it than when it was described as “an agent.

Summary

- Language can direct people’s thought processes and, in turn, our actions and reactions.

- This can be good or bad depending on the situation.

- Our beliefs, understandings, and memories are affected by language.

- language interferes with our interpretation and memories of reality, but this can be advantageous of a global understanding is more useful.

Linguistic Relativity

Linguistic relativity is the idea that different languages have different kinds of influence on people’s thoughts and behaviors.

Satisficing means not wasting your time studying all the options. Just settle on the first solution that is good enough for current purposes and stop the search.

Communicative Need

If a lion could talk, we could not understand him. —Ludwig Wittgenstein (1953)

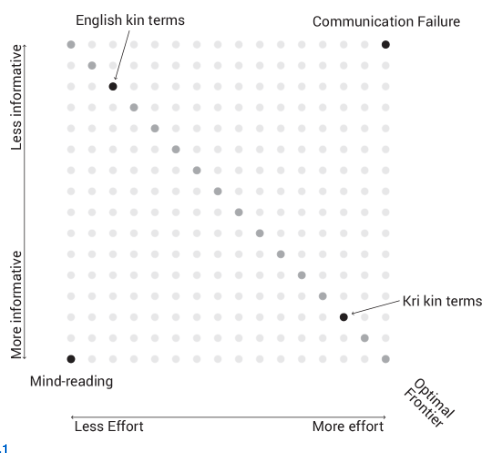

There is a trade-off between communicative and cognitive cost.

Why is it that “only a small subset of the species diversity in any one local habitat is ever recognized linguistically by local human populations”

Language as a system for coordination of action and attention. What would be the ideal communication system for this function?

One idea is to combine perfect informative (lossless) communication with perfectly simple (no cognitive cost), that is telepathy of mind-reading. But nothing like this is necessary if your goal is to coordinate with someone. We just need good enough.

Language could not faithfully transfer a complete idea or experience if it tried. There is no reason to think that when I use a word, my goal is for you to have exactly the same idea in your mind as I have in my mind. What I want is for you to respond in a certain way.

Regarding Kri Language:

The role of language is not primarily “to transfer ideas from one mind to another mind,” as is often said. This provokes a metaphor of treating images as packages.

Michael Reddy:

There are no ideas whatsoever in any libraries. All that is stored in any of these places are odd little patterns of marks or bumps or magnetised particles capable of creating odd patterns of noise. Now, if a human being comes along who is capable of using these marks or sounds as instructions, then this human being may assemble within his head some patterns of thought or feeling or perception which resemble those of intelligent humans no longer living. But this is a difficult task, for these ones no longer living saw a different world from ours, and used slightly different language instruction.

Language is a tool for instruction of imagination. Language does not provide direct access between minds because there is always an experiential gap.

As a tool, language is not for informing but for persuading.

Framing and Inversion

Man Muss immer umkehren (One must always invert.) - Carl Jacobi (1820)

We can readily flip back and forth but with many other reversible images one construal dominates.

We can readily flip back and forth but with many other reversible images one construal dominates.

Framing: how I see an image is a private matter, but how I label it is an imposition on others. Framing is a public act of influence.

Imagine a 4-ounce measuring cup in front of you that is completely filled with water up to the 4-ounce line. You then leave the room briefly and come back to find that the water is now at the 2-ounce line. What is the most natural way to describe the cup now?

If asked if the cup is half full, or half empty - 70% said half empty with this framing. If starting empty and coming back filled, only 20% said half empty.

Alternative descriptions of a decision problem often give rise to different preferences.

Framing will often introduce metaphors that can function as “tools of thought.”

Every act of framing is like one of Schelling’s maps. It makes claims about what territory needs to be traversed, and it foregrounds certain landmarks to be used for coordinating the journey. When you are handed a map made of language, remember that it is not the territory. Someone drew it. Someone chose what to include and what to omit. Someone is directing your attention to certain details and away from all manner of others. Only by being mindful of this can we decide whether we are happy to accept that map and the terms that it sets on us. Yes, language is collaborative and cooperative, even when it is competitive. But there is always someone who decides what game is being played.

Made by Language

Russel conjugation - we word things differently depending on who is the subject of the sentence. I am firm, you are obstinate, he is a pig-headed fool.

The Russel conjugation portrays the self more favorably than others.

In their 1988 book, Manufacturing Consent, media commentators Edward Herman and Noam Chomsky developed what they call a propaganda model of mass communication. They argue that the mass media serve “to mobilize support for the special interests that dominate the state and private activity.”

They single out choices, emphases and omissions in media practice.

Trump: She’s shocked that I picked her. She’s in a state of shock Vega: I’m not, thank you, Mr. President. Trump: That’s okay. I know you’re not thinking, you never do. Vega: I’m sorry? Trump: No, go ahead.

CBS News reported the incident as follows: “As tensions between the Trump administration and the press continue, the president sparred with ABC correspondent Cecilia Vega in the Rose Garden today.” CNN reporter Daniel Dale remarked on the wording of this: “One of my Trump- era media pet peeves is when Trump belittles or insults someone and it’s described with words like ‘sparred’ or ‘feud’ even though the other person didn’t do anything.”

Limited word choice

…implies that if there is an available label for something and you choose not to use that label, you are anti whatever is denoted by that label.49 The problem is that you can’t win at this game. Every time you label something, you aren’t just choosing to frame it in a certain way; you are always choosing not to frame it in literally every other conceivable way. If I see a dog and ask, Whose pet is this? am I anti-dog for not using the word dog? If I say My vehicle is parked over there, am I anti-car for not specifying that it’s a car? If I say my mother’s brother instead of my uncle, am I against uncles?

Stories and What They Do to Us

Somebody gets into trouble, gets out of it again. People love that story. They never get sick of it. —Kurt Vonnegut

Almost as a rule, heroes and heroines suffer misfortune early in a story.

- stories benefit the teller, increasing his social standing by prowess as wordsmith and entertainer.

- stories benefit the audience. A story gives access to another experience. We can learn lessons without paying the price.

- stories benefit both in social bonding.

Social Glue

When people laugh together in a conversation, it shows not only that they each individually find the same thing funny, but that this brings them together.

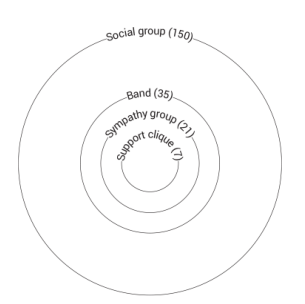

In the center is the small group of people who are closest to us. This support clique contains a half a dozen or so people. We are in constant contact with these people, and they are the ones we would turn to—and who would turn to us—when disaster strikes. Next is a sympathy group, of around 20 people, a bit farther out. Then a band of about 35 people, and a core social group of around 150 people. This group of 150 is the well-known limit of social group size such that we know all the individuals in the group and can track their relationships to each other.

In the center is the small group of people who are closest to us. This support clique contains a half a dozen or so people. We are in constant contact with these people, and they are the ones we would turn to—and who would turn to us—when disaster strikes. Next is a sympathy group, of around 20 people, a bit farther out. Then a band of about 35 people, and a core social group of around 150 people. This group of 150 is the well-known limit of social group size such that we know all the individuals in the group and can track their relationships to each other.

Sense Making

The physiological effect of surprise.

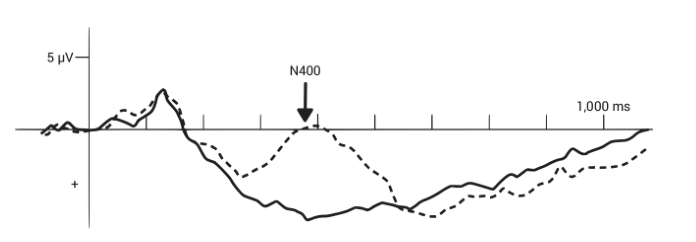

The sentence “I like my coffee with cream and socks.”

As you processed that sentence, you were not expecting the word socks. It triggered in your brain an electrical signature of surprise called the N400 effect. At about 400 milliseconds (four-tenths of a second) after an unexpected input, there is a change in the brain’s electrical activity that can be measured on the scalp.

The solid line represents “I like my coffee with cream and sugar.”

This is not the only physiological effect of surprise. Our skin conductance increases. Our heart rate changes. Our blood vessels constrict. When things go against our expectations, we respond physically. Even minor transgressions of expectation affect us directly, and this helps to explain why we pay attention to them and why, in turn, they have the mutual prominence needed to serve as landmarks in coordination games.

NOTE

Maybe this is why I chase surprise? I don’t fully see this this as a negative thing. It is stressing?

On Fiction

- our propensity to create and enjoy narrative fictions was selected and maintained due to the training we get from mentally simulating situations relevant to our survival and reproduction.

- fiction might “recruit and train our capacity to imagine other people’s thoughts”

- the simulation that fiction provides allows us to “anticipate mentally events that could occur in the future, and imagine possible reactions to them”

- fiction allows us to prepare for “real-world encounters with negative emotion and/or hostile others.”

Words should never be our trusted measure of reality because words won’t stay still. We have a duty to heed reality, always at a step removed from the thinkable verbal descriptions of it. Reality must be our ultimate mooring.

Parting Note

The way forward is to pursue collective truth seeking—an impossible enterprise without language—and make it the value that defines human well-being through a shared grounding in reason and respect for reality. For that, we need a collective respect for language itself. This respect must in part be a sense of humility at the myriad ways in which we are played by language, through the distractions, the framings, the overshadowing, the switching off of thinking, the stripping down of experience to the tiny slice of reality that language only manages to allude to. But this respect must also be a sense of awe at language’s power, at its capacity to provide shared maps and moorings, to enable social coordination, to create rights and duties, and to bring sense to our social minds, our societies and cultures, and our selves.