created, & modified, =this.modified

tags:y2025mazepaperanthropology

rel:Survey of Being Lost Asemic - The Art of Writing

Why I’m reading

Encountered in Mathematics of the Incas - Code of the Quipu where it is mentioned as a practice of creating a type of Eulerian circuit, and memorizing the path one walks to get to the land of the dead.

It is a can of worms. This is supremely interesting.

Encounter this great quote

Writing is so unreal, so terribly unreal, lending the illusion of movement to quiet and stillness, and holding back desire and vision and the cool, clear welling up of things.

Deacon writing to Gardiner, on board the SS Ormonde sailing to Malakula, August 25, 1925

Introduction

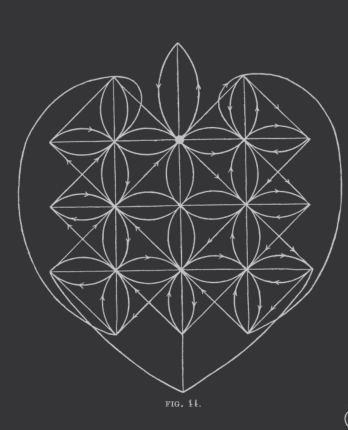

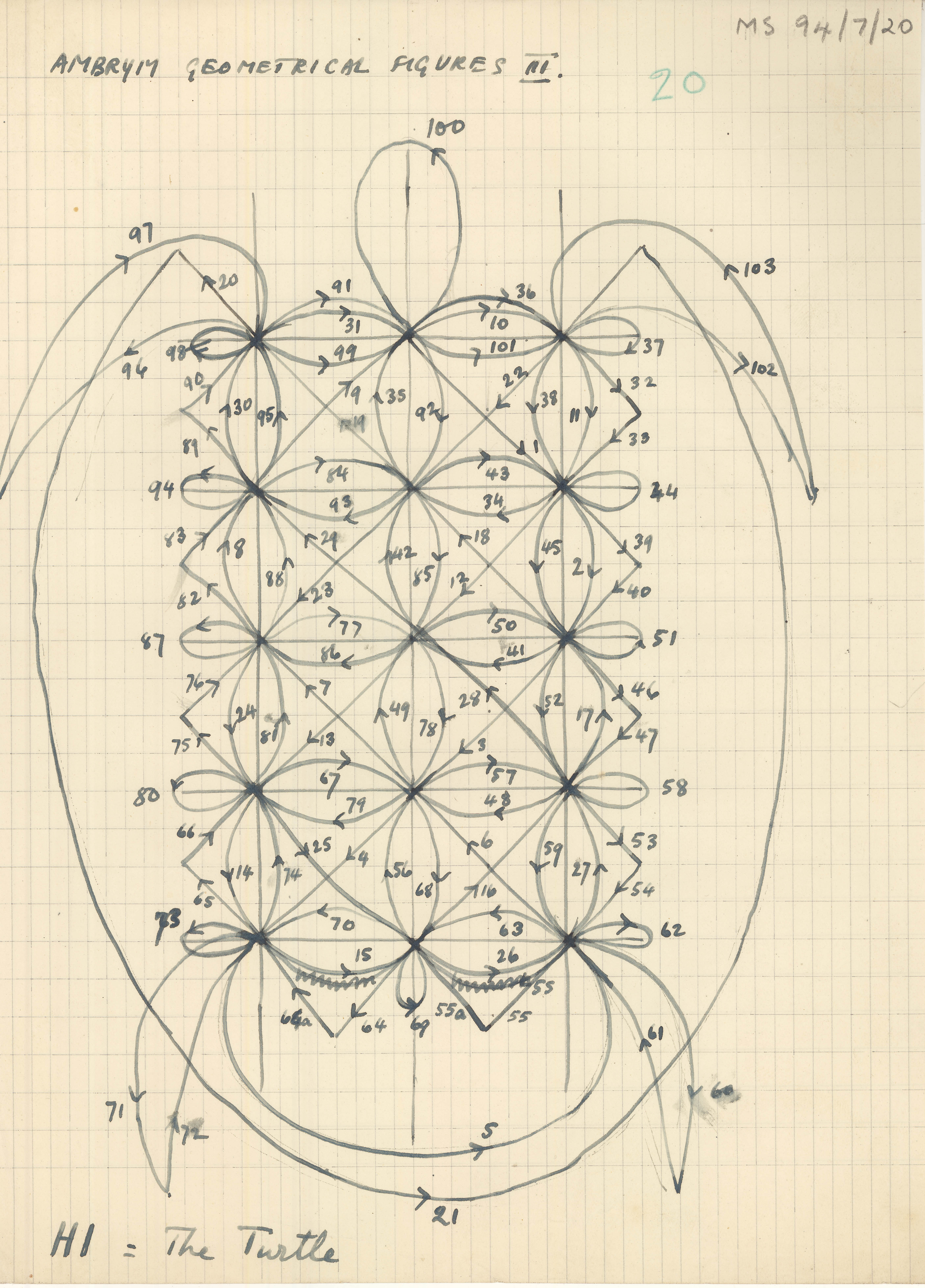

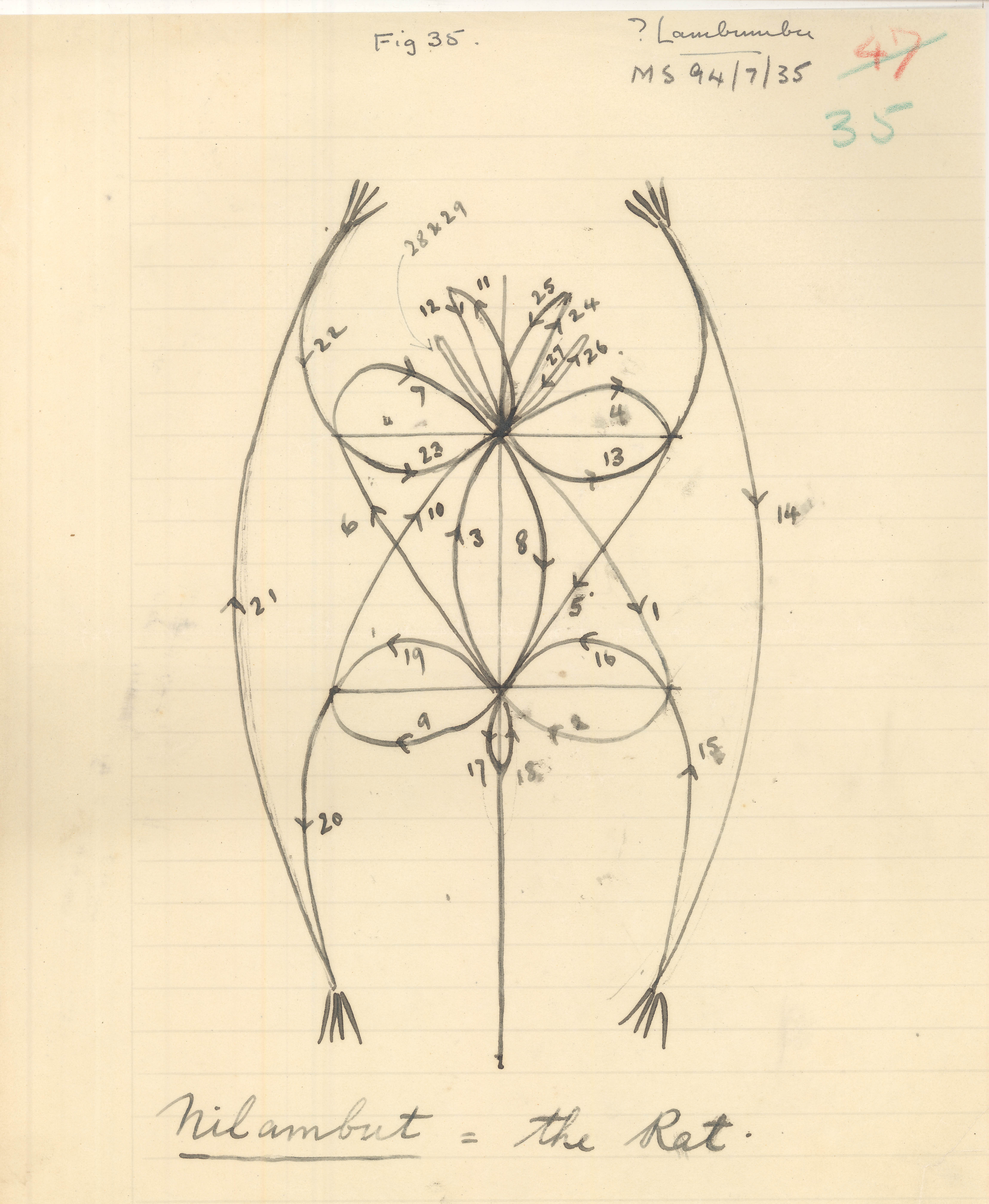

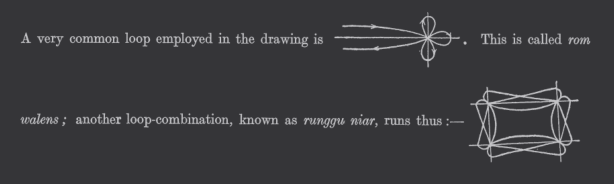

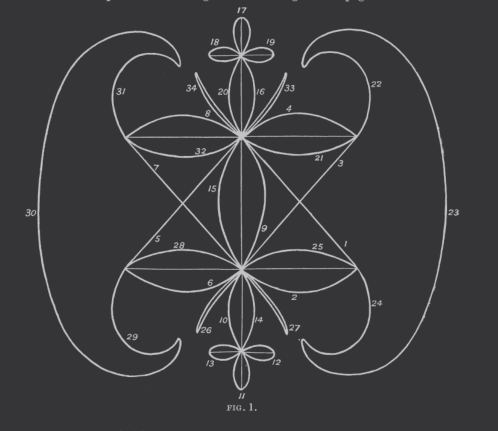

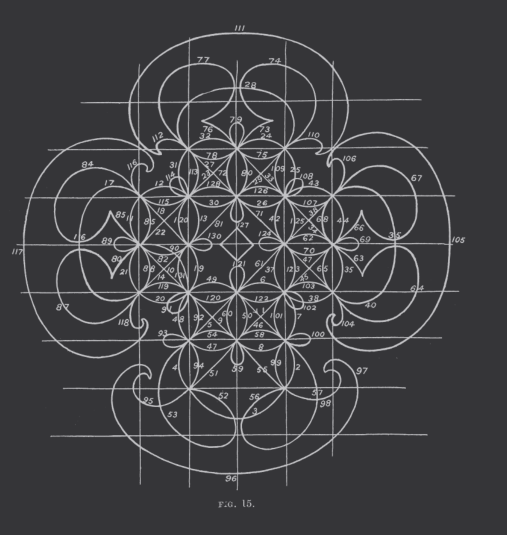

This geometrical drawing from the island of Malekula (Vanuatu) shows the universal human need to produce (tetradic) signs to visualize something else, in this case the levwaa (stump of a banana). The numbers indicate the way in which the continuous line was drawn in the sand.

The anthropologist Bernard DEACON (1934) published a collection of geometrical drawings in the Royal Journal of Anthropology of Great Britain and Ireland. This article is still a monumental publication on the topic of doodling and the inner human need to create signs.

A correspondent of Deacon (miss Hardacre) told him that the lines were drawn ‘as pastime, chiefly by the young people when sitting about with nothing particular to do. They are traced with the finger in a nice moist patch of sand, well smoothed over, or in the dust, and are drawn on the frame work without removing the finger from the ground.’

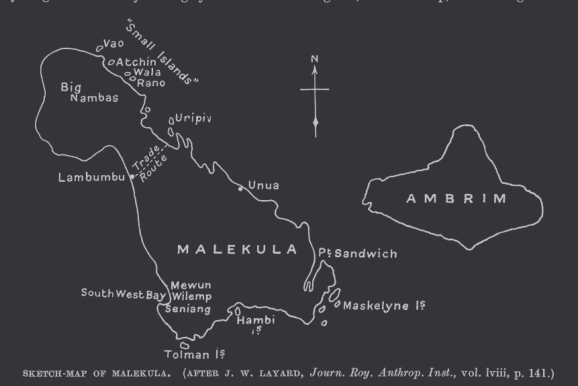

Deacon’s collection remained incomplete, because he became a victim of cannibalism (kakae). The Ni-Vanuata – People of the Land – live over eighty islands and speak about hundred distinct traditional languages. Bislama functiones as the linking language between the indigenous vernacular and both English and French. For instance, the word for piano is: samting blong watman wtem blak mo waet tut, sipos yu kilim, hem I save krae arot, meaning ‘a whiteman’s thing with black and white teeth; if you strike it, it cries out.’ John Layard (1942) also gave examples of the sand drawings in his book ‘Stone Men of Malkula Vao’.

DEACON, A.Bernard (1934). Geometrical drawings from Malekula and other islands of the New Hebrides. Pp. 129 – 176 Pl. XIII in: The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland. Vol. LXIV (Jan – June 1934).

Bernard Deacon

Seeking more information,

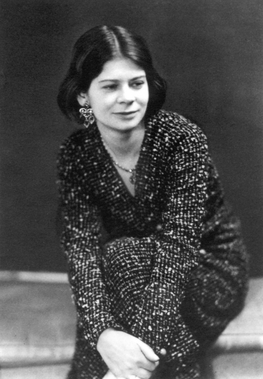

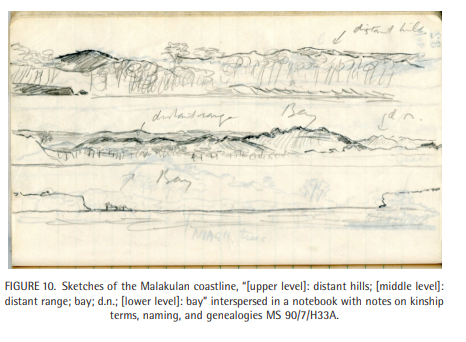

Arthur Bernard Deacon (1903–1927) was a social anthropologist who carried out fieldwork on the islands of Malakula and Ambrym in what is now Vanuatu.

Deacon had known Margaret Gardiner, a fellow student, for more than a year before leaving Cambridge, but they only started a relationship on the evening before his departure from Cambridge. Although they exchanged many letters, and arranged to meet in Australia to live as a couple, they never met again. Gardiner’s memoir of Deacon was published in 1984.

She visited his grave there 56 years later and wrote a book, Footprints on Malekula: Memoir of Bernard Deacon, in 1984.

Thought

I don’t see any reference to cannibalism as seen in the introduction in reference to death, only:

Deacon contracted Blackwater fever and died a few days later, nursed by Mrs. Boyd. He was buried on the island. Since then, locals have professed to see his ghost wandering through the dancing grounds, and some posit that his death was caused by powerful spirits who had been inflamed by the fact that he had trespassed to take photographs in a sacred space

MALEKULA is the second largest island of the New Hebrides group and is inhabited by a people speaking dialects of a Melanesian language.

He commented with exasperation in a letter to Haddon that “everyone has been led away by the glitter of civilization—rifles, gin, rum, watches, electric torches, condensed milk, tinned meat (both consumed in considerable quantities); the price of cotton, the doings of traders, these are becoming more and more the principle interests of the natives.”5 Deacon’s work has to be understood in the light of the “salvage” agenda of his time. Traditional cultures were perceived to be declining irreparably and it was the self-defined task of this generation of anthropologists to inscribe traditions before they disappeared entirely.

Deacon had left for Malakula in 1926 filled with youthful energy, but soon became disillusioned and overwhelmed. The paradigm of “salvage anthropology,” of preserving and collecting that which was rapidly being lost, provided a metanarrative for his fieldwork experience. The local culture, as he perceived it, was in decline due to the influence of missionaries and the interests of Western traders. Whole language groups were dying from introduced diseases. The area where he lived was infested with malarial mosquitoes.

Letter to Margaret Gardiner:

It is so different in physics and chemistry—there you have a vast structure of really beautiful theory, experimentally verified in enormous numbers of ways, and as undoubtedly true, I suppose, as anything of the kind one can think of—so research has a great theoretical searchlight, there is coherence and direction. Here (in ethnology) it is all a mess—I suspect most ethnologists are bad historians, or bad psychologists, or bad romanticists

In a volume edited by W. H. R. Rivers entitled Essays on the Depopulation of Melanesia (1922b), missionaries, traders, and ethnologists discussed contemporary theories of population decline in the region and concluded that the rapid decline of Melanesian peoples was a result of the negative effects of colonialism, missionaries, and trade that had brought disease, alcohol, and detrimental innovations in clothing, housing, and feeding, resulting in a profound shift in the psychological state of native peoples and a “loss of interest in life”

The paradoxical role of the anthropologist was, therefore, to document and record what was disappearing. Preserving, while at the same time facilitating the disappearance of the documentary record.

Deacon was charged by Haddon to collect skulls for the Cambridge Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, which is performed while lamenting the disappearance of entire villages and language groups.

“nothing has happened since I have been here except funerals … everything has gone, or is going, in the New Hebrides. I’m just getting what I can before it goes altogether.

For Ingold, “the practice of drawing has little or nothing to do with the projection of images and everything to do with wayfaring—with breaking a path through a terrain and leaving a trace, at one in the imagination and on the ground, in a manner very similar to what happens as one walks along in a world of earth and sky”

Sand Drawing

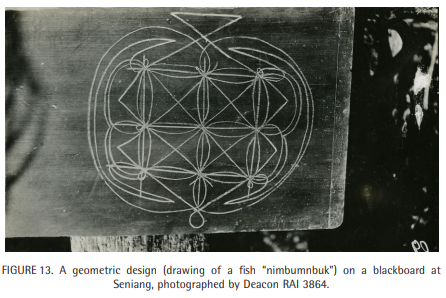

One of Deacon’s most important contributions to anthropology was his extensive documentation of the sand drawings of the islands of North Central New Hebrides (now Vanuatu), most especially from the islands of Malakula, Ambrym, and Ambae.

He recorded 118 different designs, noting the mythic significance of the drawings, and the role they play in allowing access to the world of the dead and of ancestral spirits.

Deacon noted that in the process of creating a sand drawing, “the finger never truly traverses the same route twice”

Sand drawing embodies the very definition of diffusion itself as it was imagined in Cambridge in the 1920s: its transient nature necessitating the transferal of cultural knowledge between minds, mediated only by the temporary manifestation of images.

the drawings visually instantiate key cultural narratives, some of them puzzles that must be solved using the sand drawing (as in the case of the drawing of which half a drawing is presented by the spirits to the deceased after death and which must be completed in order to enter the afterlife within the fiery volcano on Ambrym).

Deacon comments:

Deacon comments:

The whole point of the art is to execute the designs perfectly, smoothly, and continuously; to halt in the middle is regarded as an imperfection

Thought

Reminds me of prosody or performance of music, despite being purely notation. It’s as if the writing of the composition itself were the performance.

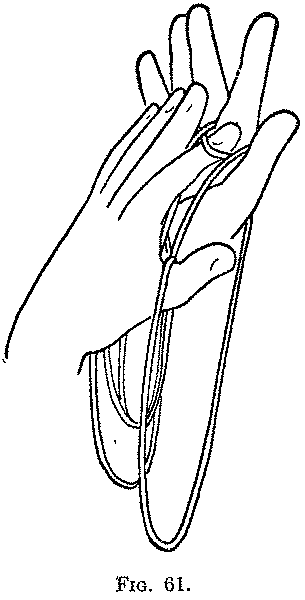

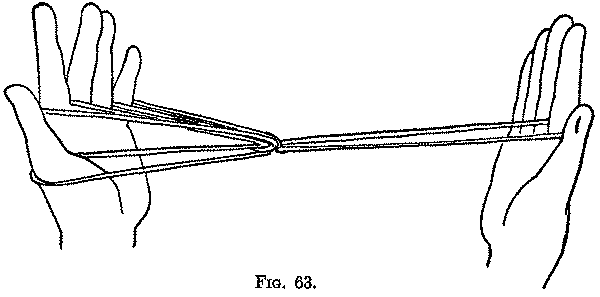

Haddon had collected string figures from the Torres Straight. To collect a string figure, a design woven on the fingers using a six-foot loop of string, is to collect a procedure and not merely an endpoint.

String Figures

rel:On HandsThis little figure comes from Murray Island, Torres Straits, where it is known as Baur = a Fish-spear (see Rivers and Haddon, p. 140, Fig. 1). It is identical with “Pitching a Tent,” of the Salish Indians, British Columbia,

Release the loops from the right thumb and little finger, and separate the hands. The points of the spear will be on the thumb, index, and little finger of the left hand. and the handle will be held by the index of the right hand

It appears there is an associated notation SFN (string figure notation)

- P1:rF pu lPS ma-tw rFN

- lF mr-th rFN pu rPS

- re rTN+rLN (at same time)

Nahal

Our own techniques of arithmetical calculation and geometrical construction are handed down in the same ‘perspicuous’ fashion (Wittgenstein, 1978, III, § 1), though memorization is less crucial in our written tradition. ‘A rectangular area’, Deacon explains, ‘is made level and smooth on the sand, or ashes are spread over the surface of the smoothed earth.’

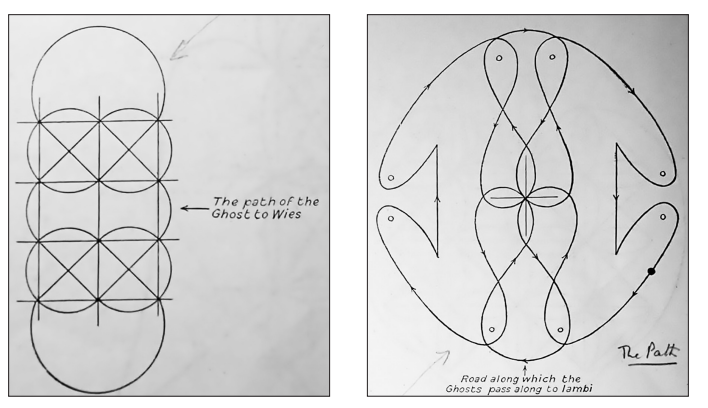

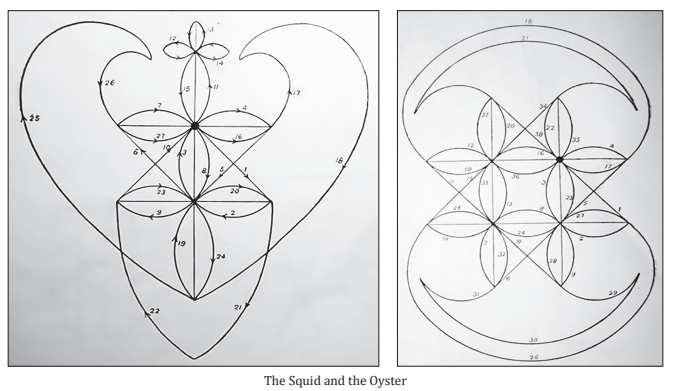

The islanders had a belief in the journey of the dead. In Seniang the ghosts of the dead were said to pass along a road to the land of the dead called Wies. Along this road they had to pass a rock inhabited by a dreaded ogress Temes Savsap. Traced in the sand before her is the figure Nahal to route to Wies going through its middle.

As the ghost approaches, Temes Savsap wipes out half of the tracing and tells the traveller that before he proceeds any further he must complete the diagram correctly. Most men during their life-time have learnt how to make this and other geometrical figures, and so, on their death, they are able to do as Temes Savsap tells them and pass safely on their way. But should a man be ignorant of how to complete the figure, Temes Savsap seizes him and devours him so that he can never reach the land of Wies

On the ground in front of her is drawn the complete pattern know as Nahal, “the Path”

The path that the deceased must go through so as to accede to the land of the dead lies exactly in the middle between the two symmetrical halves of the drawing. But as soon as the dead approaches it, the female ghost hurriedly rubs out one half of the pattern, so that the dead cannot find their way any longer. Only precise knowledge of how to redraw the missing half of the pattern will enable the dead to see the path again. However, if dead people do not know how to complete the pattern, the female guardian of the path eats them, so that they will never reach the land of the dead.

Drawing to Tell Versus Drawing to Intrigue?

A relentless critical evaluation in the process of drawing lines will not lead to a successful drawing. In the moment of the gesture, during which we cannot control the outcome, the unexpected can emerge. Since, in the action of the gesture of drawing, the control of our conscious thinking is limited, the outcome is often considered to be accidental. But an individual’s gesture, as well as an individual’s voice is the most significant utterance expressing a unique identity.

In today’s context of visual communication, it is not the virtuosity of drawing that is the ultimate goal anymore, but rather, the recognition of how important it is to fnd a balance between intuitive processes and conscious processes of thought

Geometrical Drawings From Malekula an₫ Other Islands of the New Hebrides

A famous warrior named Airong died. His ghost passed along the road leading to Wies and came across Temes Savsap sat with the Nahal half rubbed out in front of her. He had never learned the figure, he sought in vain to pass the rock but could not. The guardian was about to devour him when he turned back and ran back along the road.

The watchers by his body on the funeral stretcher saw him wake up and heard him ask for bow and arrow. He had become alive again. They thought him made but brought the bow and arrow to him. He said

” If you look out to-morrow and see that the rock (of Temes Savsap) has fallen into the sea, then you will know that I have killed the Temes.”

before becoming rigid again in death. When he came near the rock he drew his bow and, aiming at the Temes, shot her dead. That night the rock crashed down into the sea. Next morning the people from all round Benaur went to look, and saw the rock fallen into the sea. Ever since, the ghosts have passed freely on their way to the abode of the dead-the Temes and her sand-figure have gone.

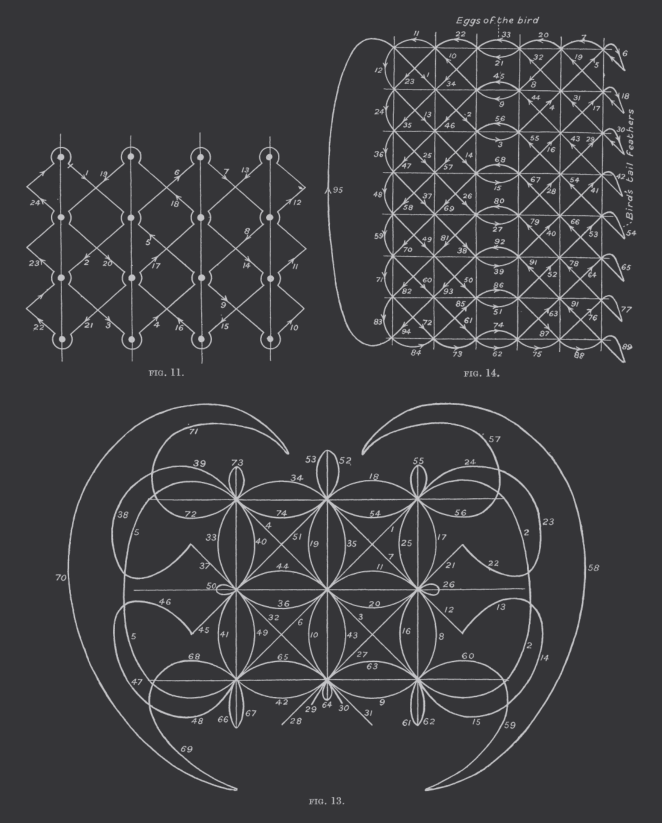

Different Asterisms are present in the tracings,

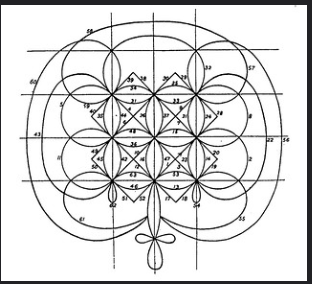

Nul Sagavul: The Pleiades. This is an actual tracing from a native drawing and is a good example of the accuracy of hand and eye possessed by these people. There are supposed to be ten stars (sagavul = 10). Each apex represents two stars (as numbered by the informant), indicated it seems by the two lines converging to form the point.

Navanevis Mar Mbong Lamp: Navanevus means the heart; Mar Mbong Lamp is the owner of the heart. The framework of squares is first constructed with the central vertical line, which is longer than the others. The four circles around the squares are then drawn. The rest of the figure is built up by one continuous line. The extension at the top is the “throat” of the heart-the pipe leading into it. The shape of the complete figure, and the four-fold partitioning of the central part emphasized by the four separate circles, are remarkable and suggestive. The story of the figure is as follows: Mar Mbong Lamp of Ranmbwengk village was married to two women. Now it happened that he quarreled with his wives’ brothers, and a great battle took place between him and them. During this battle he was very sorely wounded; arrows stuck into him all over his body and he was near to death. He therefore betook himself to his sacred place, and there hung his heart upon a tree, leaving some arrows sticking in it. Having done this, his strength was restored. He went forth once more to fight and succeeded in killing many of his wives’ brothers. This he continued to do for many days, returning in the evening to the sacred place, where he kept into his heart, and thereby kept himself alive. His two wives were distressed at the slaughter, and they took counsel together, saying: “It is bad that all our brothers should die. Let us go to the sacred place and see what it is that he keeps there, so that we may steal it.” So they went to the sacred place, saw where the heart was hanging, and took it away. That evening Mar Mbong Lamp, pierced with many wounds, went to his sacred place and found that his heart was gone. Being unable to creep into it, he could not recover from the wounds, and so he died.’ From Seniang. The same figure is found in Lambumbu under the name Nesnen (= the intestine), but no record has been preserved of any legend concerning it in this district.