created, & modified, =this.modified

tags:y2025musichistoryperformance

Why I’m reading

Sometimes I’ll encounter a piece of technology, or an object – say a skateboard, and it’s at some kind of evolved state, that I really don’t fully consider the path it took to get there.

And sometimes when I do consider this, I wonder about the offshoots; why are the wheels like this, and the tail like this etc? What kind of slow creep of change is still occurring? (similar to how in guitar, the novice will always end up buying different trinkets, supplements and tools that would ease use or otherwise be snakeoil) But why do we accept some degree of difficulty, or pain with these objects? Why should the strings hurt? Which technologies of music are stable?

So back to this music performance issues, what I hope this book is about, is different almost engineering issues that were encountered in this period of music.

At least, in time I want to know these things. I handle a guitar basically daily, and I want to know.

Thought

Yes, this might be what I wanted!

The metronome (invented in 1816) is an excellent training tool for rhythmic steadiness, but this usage did not become universal until some point in the twentieth century. Countless reports from preceding centuries document the rhythmic instability that posed a major obstacle for even the best ensembles. Leaders had to resort to audible time beating, whether by stamping the foot, pounding Issues: 1600-1900 with a stout rod, or playing the first violin part at deafening volume.

Our Evolving Language

*We cannot imagine a world in which the only music was live music.

Thought

Right off the bat, “We cannot imagine a world in which the only music was live music.” I’m wondering what my life would be filled in, if I didn’t have access to the music I listen to. My immediate question was if I’d end up playing more music, or creation of music would be a greater emphasis than listening.

Musical education of this time was limited. Most German orchestral players lacked a general education beyond elementary school.

Friedrich Wilhelm Marpurg’s music journal (Berlin, 1760) notes that “many musicians have no sheet music at all and often only musical instruments of poor quality; without music and good instruments, they are almost not musicians.”

Handwerker

In Germany the mediocre professional musician was pejoratively a Handwerker, “who knows nothing more than to apply his fingers to the produce the notes; his playing reflects a simple mechanical practice and blind imitation more than his own thinking. He rises to the level of Künstler [artist] when he knows the theoretical basis of his art and applies this knowledge to his playing.”

The upper-class pursued music as accomplishment and not profession. Composition or writing music were more acceptable endeavors.

rel:Stability of Concepts

The terms amateur, dilettante and Liebhaber are vital to understand at this time, all implying achievement below a professional player.

Today’s dictionary dilettante: a love of the fine arts, who cultivates them for love rather than professional, and amateur as one who interests himself in art or science, without serious aim or study.

In the 18th century a dilettante was a trained musician who played perfection, but for pleasure rather than for a living; he was performer of professional caliber with amateur status – without the unfavorable connotation we have today.

These terms referred not to proficiency, but to socioeconomic class.

Amateur

According to the Dictionnaire de l’Académie françoise (1694), an amateur is devoted to something; hence, an amateur of virtue, of the arts, of good books, of paintings, etc. Jacques Lacombe’s French dictionary of the fine arts (1753) defines the amateur as one who distinguishes himself by his taste in and knowledge of one of the fine arts, although he does not make of it a profession. We also owe much to this class of amateurs who enlighten our taste and extend our knowledge by their writings.

What needs to be made more explicit to the modern reader is that the amateurs taking part in concerts are playing alongside professional musicians, but without remuneration.

1971 Pierre-Louis Ginguené’s 3 types of amateur

- those who do not practice music, but retain lifelong taste for it. Their nature and sure instincts make them better judges of music than those that lack taste or impartiality.

- developed natural gifts by study and contributed which contributes professional level of achievement.

- smallest and most distinguished, these want to study music theory and judge the practice better.

Unlike dilettante, amateur, and Liebhaber, which originally denoted social class, the following terms concern achievement. Kenner and connoisseur comprise those who are knowledgeable about the technical aspects of a subject.

“It is easy to see that the … modest Dilettant can very often with more right deserve to be called a true artist and musical expert than can the artist of Handwerk.”

The dilettante/enthusiast can practice art free of necessity and outside pressures, giving him advantage over professional musicians.

Upper-class women often achieved extraordinary musical skills for their time, but were restricted to performing for their peers in private settings.

Bach’s Lament about Leipzig’s Professional

In Bach’s time German towns and cities employed instrumentalists to play at specified times daily form the town tower. They sometimes also acted as watchmen.

Literacy:

Among a hundred Stadtpfeifer journeymen, he says, would scarcely be found one “who can put ten ordinary words on paper without error.

As a rule, the designated instrumentalists for church music comprise a company of four to six persons, who often have neither good intonation nor rhythm, neither music nor anything else that is most indispensable to even only mediocre music. With every bowstroke and every attack on their instruments they produce tones arousing disgust and distress.

The State of the Instruments

The earliest book to offer composers substantive guidance for all the basic wind and brass instruments is Louis-Joseph Francoeur’s Diapason général de tous les instruments à vent (1772)

Intonation was a major problem. Brand new instruments were seldom in tune.

Rarely is a blown instrument in tune when it leaves the maker’s hands

Johann George Tromlitz in 1791:

I do not believe that there exists an instrument on which it is more difficult to play in tune than the flute. Many factors contribute to this: first, the natural unevenness of the tone of the instrument; blowing too hard or too softly; incorrect embouchure; a badly trained ear; an improperly tuned flute. Experience gives enough proof of this.

Strong springs, stiff reeds – the balance was not yet consistent, resulting in difficulty.

Justus Johannes Reinrich Ribock discusses the impact of tools

“The extraordinary difficulty of the oboe will always make such men as Barth, Fischer, Le Brün, and Besozzi a rarity… . An extra good reed is seldom achieved, and without it, nothing worthwhile can be done… . The best softened reed never speaks well before it has been pacified by playing; that is, before the steel lips give out and one has to put the instrument down. If the flutist can practice for an hour, the oboist measures his time by minutes.” Since purchased reeds are seldom usable, he adds, the player has to show his hand at cutting, which not everyone can do. Add the qualities of art and science necessary for a virtuoso, and “one has to be astonished not at the rarity of such men as I have named, but much more that any exist.”

Thought

I suspect access to better tools was gatekept. An easier tool to use, would cost more. If you are a wonderful musician technically, you will always sound off in an unpredictable instrument.

Not that playing out of tune is invalidating, especially today where everything has a place, but I wonder if a player might learn the idiosyncrasies of their defective instrument and then adapt to them. It’s just lacking a universality.

Exceptional stamina was required to play wind and brass instruments. “Many trumpeters, oboists, flutists, etc. have to strain their lungs to such a degree that not seldom a resulting lung disease shortens their career.”

Fingering woodwinds required hole covering or crossfingering. Othon Vanderbrock advised composition in keys lacking sharps and flats.

Thought

The limitations of the tool are directly affecting the composition of the piece.

Bach had had to make do with the “most wretched orchestra.”

Even with today’s greatly improved instruments, such individuals would be likely to produce loud, displeasing tone. This volume was probably the major factor necessitating the “screaming” reported in German choirs.

The liberhaber and students were not professional musician, but their high educational level would have produced playing skills superior to town musicians trained in playing dance and tower music.

Choral Singing Before the Era of Recording

Loud time beating in the form of foot-stamping or stick-pounding was often necessary to hold an ensemble together.

The singing itself was loud with training that leads to coughing up blood at times: “Can one remain indifferent to the fact that the young people’s health is being ruined by such enormous exertion and excess?”

Accepting Women’s Voices Boys would lose their high voices too early to be of service. “The female sex has no opportunity to study singing at school, and from an absurd prejudice (at least in most places in Germany) is excluded from singing in church music; indeed basic instruction in music is completely neglected for them (again in most places)”

18th century music was composed much better than it was performed. In the 19th century, literacy and educational standards increased, allowing better tone quality and musicianship.

Most a capella Music Could Not Have Been Sung Unaccompanied

1717 - Where are the singers who can sing a single aria without instruments and stay on pitch?

It is suggested that vocal music must always be accompanied with instrument, so the pitch does not drop – as happens without help.

“No Voice has ever been found able (certainly) to sing steadily and perfectly in Tune, and to continue it long, without the assistance of some Instrument”

Thought

The body in instruments? Could this survey be done? #body-instrument

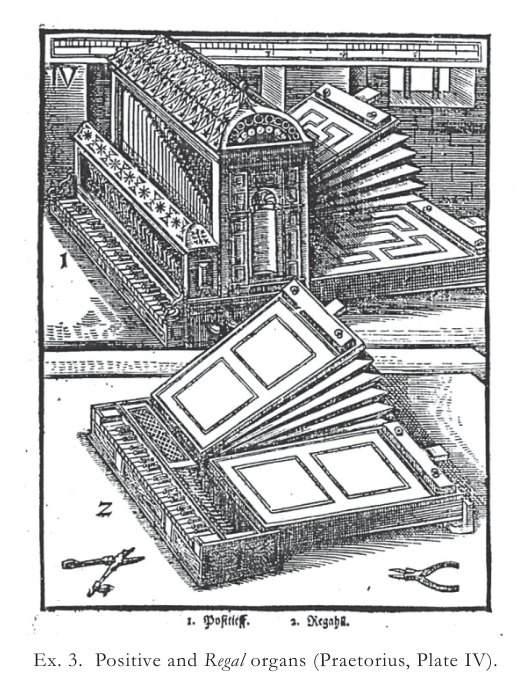

Placed in the midst of the choir, its pitches were easier to grasp than those from a large organ at some distance, whose pipes were enclosed in a case. Because less volume was required from the portable organ, its tone would have been nearly covered by the singers, giving an illusion of unaccompanied singing.

A capella describes not only unaccompanied singing, but also that with a organ/instrument doubling the vocal lines.

The Beginning of True Choral Singing

Talented young people never have the opportunity to hear something excellent, which could serve as a model for imitation. At least this is the case in all the cities where there is no court that keeps a Kapelle [musical establishment]. The number of these is certainly 30 to 1.

George Frideric Handel’s Casting

Finding a suitable bass was rare. Italian operas were training in the higher registers.

The bass Handel employed in all his oratorios from 1743 onward was the German Thomas Reinhold. After his death in 1751, the composer was unable to find a suitable replacement.

Intonation Standards and Equal Temperament

How the tonehole was decided was a matter of experimentation

… by the confession of even the best makers whom we have consulted, the pitches [for each note] of their instruments have always been made experimentally and gropingly.

1783: “It is usually said that two flutes are seldom in tune and three, never… .”

Our ears, including the general public have been trained by hearing in-tune music every day. Early musicians had none of these resources by cultural default.

German organists would prelude to assist the tuning of instruments.

Equal Temperament

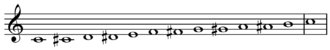

An equal temperament is a musical temperament or tuning system that approximates just intervals by dividing an octave (or other interval) into steps such that the ratio of the frequencies of any adjacent pair of notes is the same. This system yields pitch steps perceived as equal in size, due to the logarithmic changes in pitch frequency.

At this time the only tuning aid was the monochord but it was difficult for a number a reasons

- hard to tune a pipe to a vibrating string

- when struck the pitch is higher than when it at rest, so it can not have an even beating.

Monochord

Pythagoras performing harmonics experiments with stretched vibrating strings.

The monochord consists of a metal string stretched over a hollow resonating body. Using a movable bridge the string can be divided into two portions whose lengths may be set at any ratio to give various pitches and musical intervals when plucked.

Pythagoras and his followers believed that the whole universe could be understood in terms of musical harmonies and simple mathematical ratios.

Early theorists favoring unequal temperaments seem to have assumed that an interval that sounds in tune is mathematically pure or nearly so, but modern studies show the human ear has no predilection for pure intervals except the octave, and the size of the interval can vary dramatically while still sounding in tuen.

The false correlation between in-tune intervals and mathematical purity is the crux of the matter.

18th Century Stringed Keyboard Instruments

In a clavichord a blade hits the string, and stays on the string, allowing pressure to change pitch. A harpsichord uses a plectrum to hit the string. It required more hand strength.

The loud harpsichord could play a simple part to make the beats clear for the ensemble. This was later changed with the pianoforte, which allowed for a more mellow tone to fit into the music.

The action on the harpsichord could be high to achieve great volume. It could deform fingers.

When one lets a young man use his slender fingers on three registers of a poorly quilled harpsichord, he says, the fingers are scarcely strong enough to engage all three at once. At the least, he has to use all his strength to make the tones speak.

Of the harpsichord, it was required too much skill from both builder and player. “Each jack had a spring made of wild-boar bristle, whose function was to return the tongue of the jack back to its original position.”

Experimentation of tongues:body-instrument “Besides arming the tongues of the jacks with crow or raven quills, several other means were tried by which to produce a softer tone, and to be more durable; … leather, ivory, and other elastic substances were tried, but what they gained in sweetness, was lost in spirit.”

Early Pianoforte issues:

Calling the fortepiano a “defective” instrument, Cramer says that adjacent notes make a poor effect if the player does not have a spring in each finger. Thus composers need to make melodic intervals farther apart to lessen the adverse effect of their sounding with the already played notes.

Thoughts

I wonder if the improvement in expressive quality of the instruments of the end of this period, had any influence on the Romantic period (1830 and 1900) of music.

Reading elsewhere on this maybe there is a case to be made,

Romantic music showcased expressiveness and passion and was deeply intertwined with other art forms of the time, including visual arts, theater, and literature.

The construction and variety of musical instruments changed dramatically during the romantic period. The piano expanded from 5 to 8 octaves, woodwinds improved in range and quality, and the valve was introduced to the brass family. New instruments, such as the wagner tuba, were developed to create specific types of sounds

The Tromba and Corno in Bach’s Time

Composers lack guidance on these instruments limitations. They wrote in their own instrument, normally the keyboard or violin.

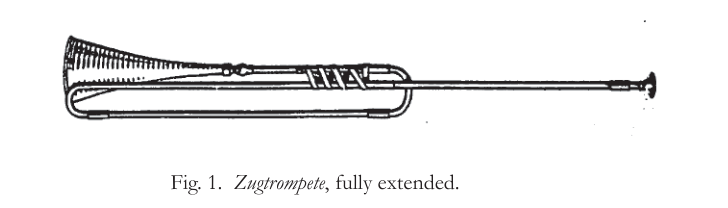

The zugtrompete was identical to the fixed-pitch trumpet but allowed an almost complete chromatic scale from middle to upper registers. They were a workhorse passed around town musicians till unplayable. In contrast, natural trumpets from courts have survived because they were richly ornamental valuable objects in themselves.

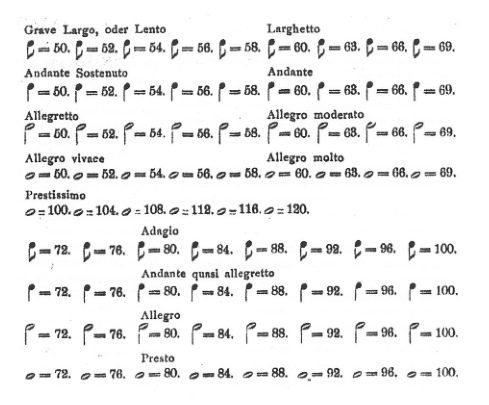

Beethoven Metronome Marks

Beethoven’s hearing loss is a major factor when considering his tempo marks. By 1799 its magnitude was sufficient to make him avoid society.

When conducting in 1814, before preparing his first tempo numbers, he was ahead of the orchestra as much as ten or twelve measures.

On the metronome, they were unaccustomed to working with the machine, and accustomed to rhythmical inaccuracy. Selecting an appropriate tempo could be difficult.

1806 Friedrich Guthmann

Whoever can and wants to keep time precisely according to the Taktmesser throughout a whole piece must at the least be no very sensitive and expressive player. Such control of the expression must also lead to an inevitable stiffness in performance; in most cases, it is even contrary to the spirit of true music. Therefore, the Taktmesser’s true function should be more to indicate the initial tempo than to require following it strictly throughout the piece during the increasing fire of execution and dense profusion of ideas. The greatest artists have also shown that they cannot play in harmony with such a mechanical instrument, for it is contrary to their sensitivity, and they instinctively depart from it.

Camille Saint-Saëns requested standards:

“This instrument is employed universally. Unfortunately, it can be useful only under the condition that it is an instrument of precision, which is scarcely ever the case. The musical world is filled with metronomes that are poorly constructed and poorly regulated [for accuracy], which mislead musicians instead of guiding them.”

Mäzel’s charts of tempo markings

Tremolo

Mozart, discussing normal and artificial vibrato in a letter to his father:

Meissner, as you know, has the bad habit of making his voice tremble at times, turning a note that should be sustained into distinct quarter notes or even eighth notes—and this I never could endure in him. And really it is a detestable habit and quite contrary to nature. The human voice trembles naturally—but in its own way—and only to such a degree that the effect is beautiful. Such is the nature of the voice; and people imitate it not only on wind instruments, but also on stringed instruments and even the clavichord. But the moment the proper limit is overstepped, it is no longer beautiful—because it is contrary to nature. It reminds me of jolting the organ bellows

Skeletal notation and Embellished music

Originating in Italy, free embellishment in vocal music was in theory restricted to a certain type of aria, as the French observer Laurent Garcin explains (1772): “In arias of a cantabile genre, the Italians have granted their singers great liberties. These types of aria are composed with few notes, sufficient only to maintain the melody. The singer may fill them up as he pleases, and sprinkle there all the ornaments of his art.”

In 1771, a bare Italian skeletal notation and an example of how a performer might ornament it below.

According to Schulz, the fashion for varying led to a vicious circle. Viewing with dismay singers’ slipshod variations and harmonic errors, composers wrote out the figuration in full: “Now the singers began anew to add ornamental notes; the composers, too, yielded and wrote out still more notes until the now customary and yet ever increasing trimmings were reached, whereby the syllables and whole words become unintelligible and the melody is transformed into an instrumental part.”

Kuhnau. In 1700, Johann Kuhnau, Johann Sebastian Bach’s predecessor in Leipzig, noted that the castrati garner the honor of being the most outstanding singers. But when they lack knowledge of composition, he adds, they often tack on embellishment that fits with their part and the harmony as little as a fist fits in the eye

Castrato

A castrato (Italian; pl.: castrati) is a male singer who underwent castration before puberty in order to retain a singing voice equivalent to that of a soprano, mezzo-soprano, or contralto.

As a castrato’s body grew, his lack of testosterone meant that his epiphyses (bone-joints) did not harden in the normal manner. Thus, the limbs of the castrati often grew unusually long, as did their ribs. This, combined with intensive training, gave them unrivaled lung power and breath capacity.