created 2025-06-30, & modified, =this.modified

tags:y2025surrealism

rel: Surrealism Dada & Surrealist Art by William S. Rubin On Ethnographic Surrealism Survey of Being Lost Mazes and Labyrinths - Their History and Development by Matthews

Quote

“The dream is not content to compensate desires dead from inanition, it may also give life to what is cold and abstract in our waking thought”

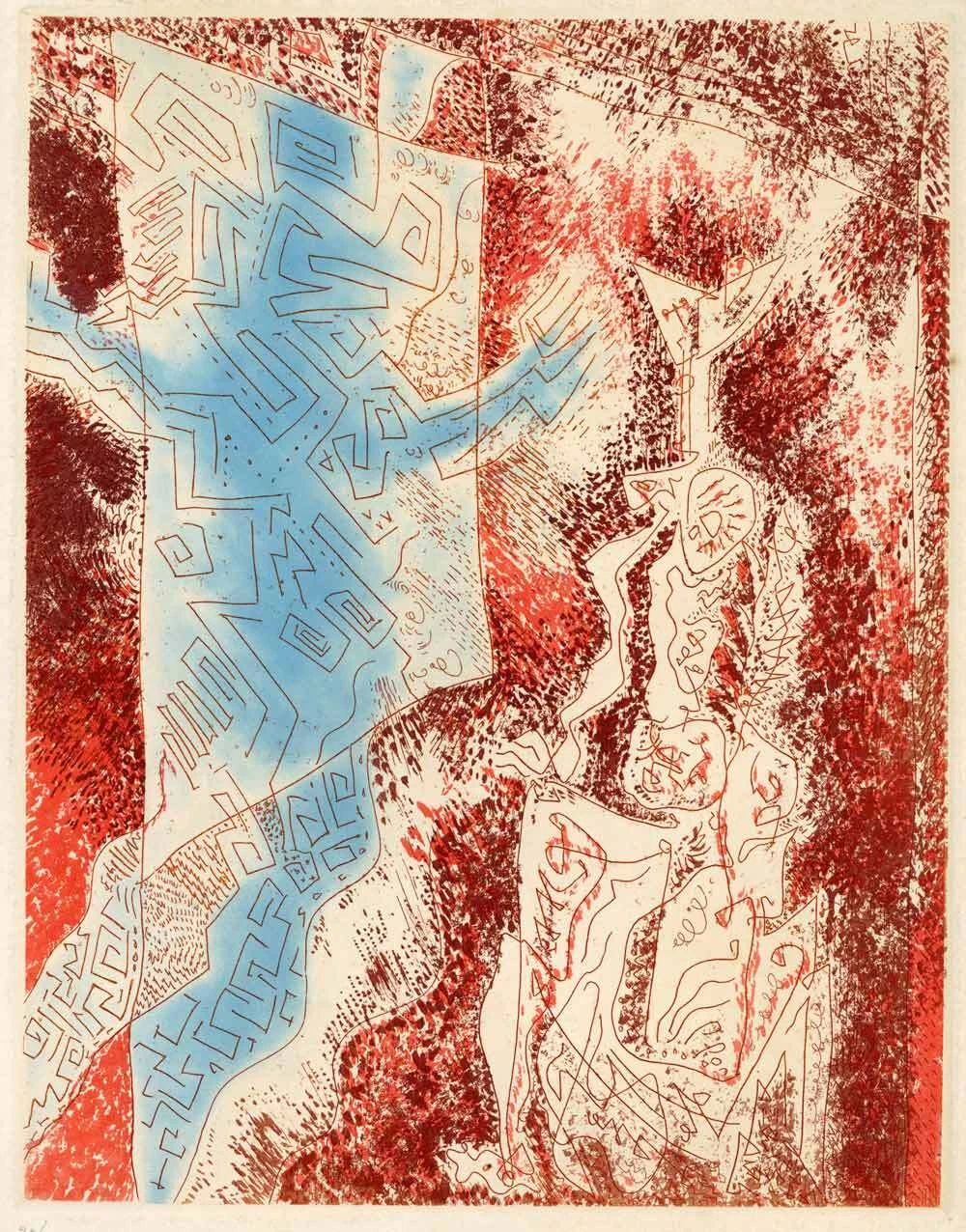

André Masson. Le labyrinthe. 1938.

In 1917 Masson, volunteering as a French soldier was shot during the Great War. Masson claimed he experienced the “ecstasy of death” and saw a “torso of light” in the sky as he lay on the ground, wounded and waiting for the stretcher bearers.

During his time at the front line, Masson witnessed first-hand the horrors of war and was deeply affected by it. Afterwards, he suffered from insomnia and when he did sleep, he had nightmares. In these nightmares Masson dreamed new paintings

Patrick Waldberg argues Surrealism can be divided into two classes (though not absolute.)

- Emblematic, painters like Mason and Ernst, “the idea is simply suggested without concern for exact representation.”

- Descriptives or Naturalists of the Imaginary, where the scene is unreal, but the settings and objects which comprise it are painted with fidelity.

Masson was expelled from the Surrealists by Breton, because Masson did not agree with the relationship to the Communist Party.

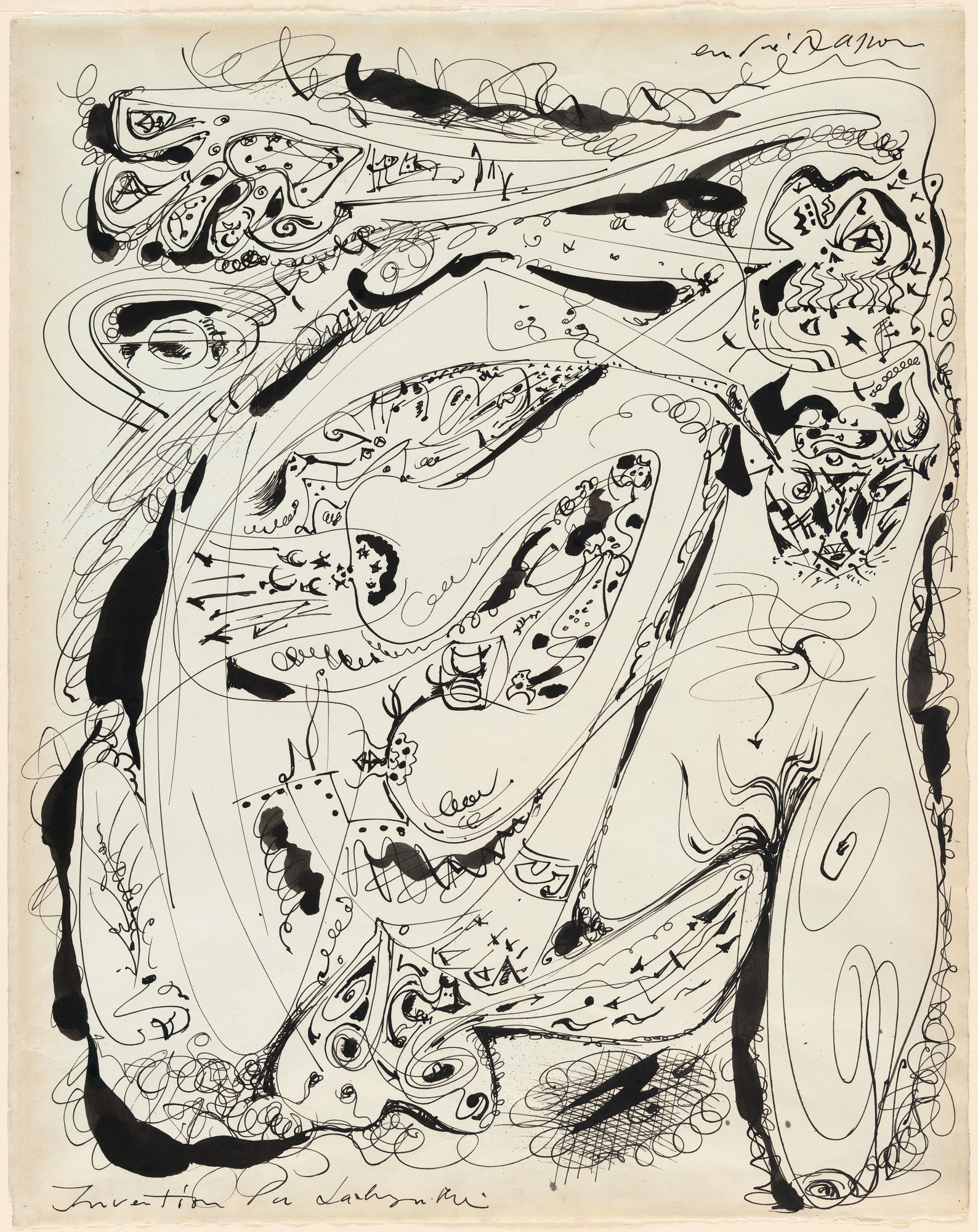

Invention of the Labyrinth

Masson was believed to be introduced into Grecian mythology through Friedrich Nietzsche. Masson publicly acknowledged the a need for Surrealism to find sources in pre-classical Greece.

Masson was also influenced by his move to Spain in the mid-1930s where he encountered the bull.

Birmingham contrasts Picasso’s representation of the bull as being, “from the playfully erotic to the pathetic” to the bulls in Masson’s works which are “ruthless monsters – unequivocal symbols of darkness and brutality”

Lady in the Labyrinth

These ideas are repeated in his 1937 painting L’unisers dionysiaque in which Masson incorporates the labyrinth inside the body of the Minotaur. This idea evolves even further in his 1938 painting, Le labyrinthe as the Minotaur grows more grotesque than the previous versions and the labyrinth inside him is much more complex. The body of the beast, once strong and muscular in earlier works, now withers away into a deformed, white husk.

The Minotaur stands tall with its insides on display like an unfinished autopsy. Its bones and organs have been replaced with stone stairways, mazes and Grecian pylons.

The once hybrid man-beast has become a hybrid beast-labyrinth and in doing so, has lost virtually all of its recognisable features; two horns, one attached, one not, and the bovine-shaped skull are all that remain of the Minotaur’s once powerful form. The loss of reason frequently associated with the myth of the Minotaur has eroded away the Minotaur’s identity. It has become the maze which it was kept prisoner in for so many years.