created 2025-06-25, & modified, =this.modified

tags:y2025fibernexusmythcomputersholes

rel: Radical Fiber - Threads Connecting Art and Science Survey of Text Etymology, Connections to Fiber, Body Jacquard’s Web Quipu

Important

Connecting thoughts and notes from Survey of Text Etymology, Connections to Fiber, Body under the topic of “fiber” as the original nexus got too bloated and needed specialization here.

Quote

Knitting is Turing complete, meaning there are a non-zero number of universes where the malevolent, genocidal AI is manifest in a quilt @ctrlcreep

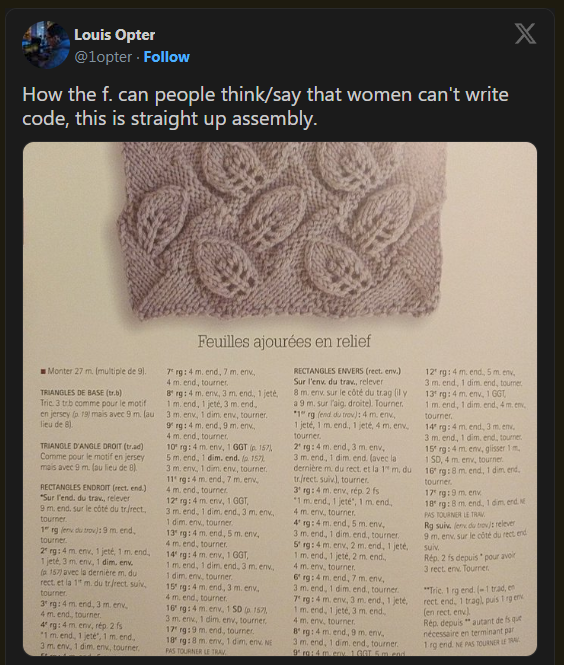

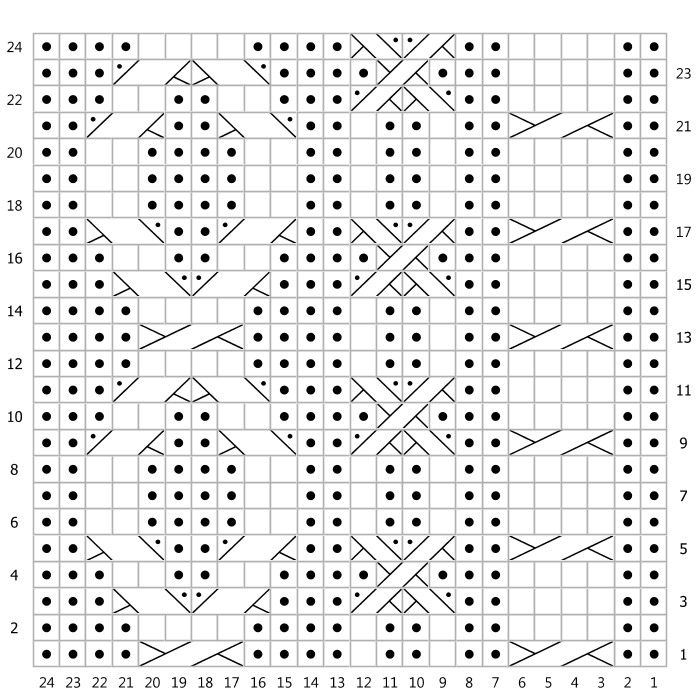

Knitting patterns are akin to machine language (machine instructions) where the output of the series of patterns/algorithmic process produces the finished object (scarf, socks etc.)

There are variables in stiches and rows. The needle itself holds an array of stiches which are knit over a number of rows.

There are conditionals to determine which instructions to follow, as row 1 might have different pattern than row 2.

rep is the iterator, meaning repeat the current set of instructions.

There are various functions such as yo, k2tog, k, and ssk – each one a different way to process a stitch.

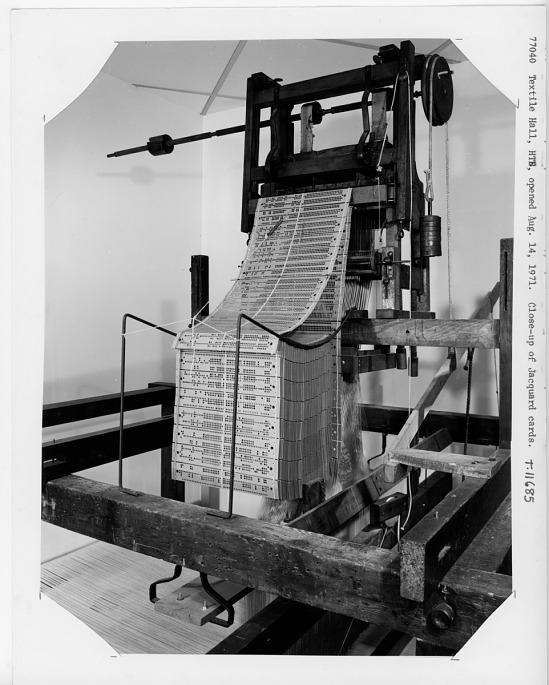

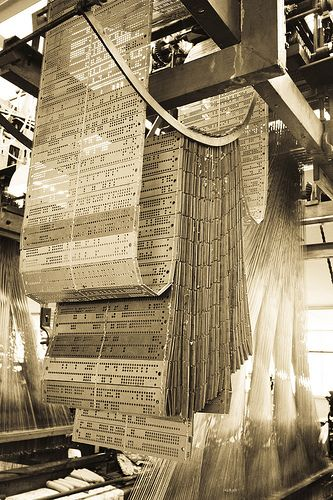

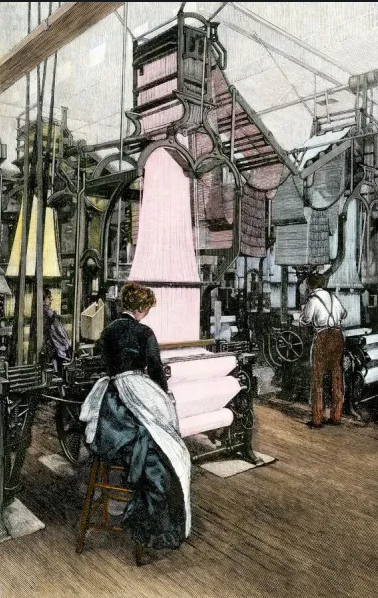

Jacques de Vaucanson was a silk inspector who turned his efforts to mechanizing the cloth-making process. He created a water-powered automatic loom. This was largely ignored till picked up by Joseph-Marie Jacquard, who patented his invention of the automatic loom in 1804.

Provided some input, a pattern could be encoded into the woven fabric. The nature of the punch card allowed designs to be reused and the mechanical process less taxing on the part of the creator.

Provided some input, a pattern could be encoded into the woven fabric. The nature of the punch card allowed designs to be reused and the mechanical process less taxing on the part of the creator.

There isn’t a universal notation for knitting patterns and different cultures have differing names for stitches. An English double crochet stitch is an American single crochet stitch.

There isn’t a universal notation for knitting patterns and different cultures have differing names for stitches. An English double crochet stitch is an American single crochet stitch.

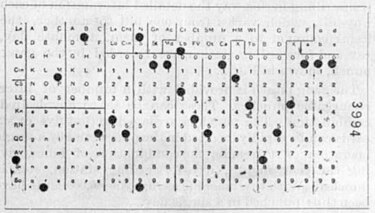

Punched Cards

Thought

Punch cards are interesting in the sense they are destructive, entropic if are not just a mark, but actual Holes. You create a puncture in a sheet.

I think of a punch into a piece of paper, like with a holepunch. The memory is maintained in the main body of the paper, but the information is ultimately lost by the ejected punch hole (captured in a reservoir or subject to gravity and wind) . If you could maintain the state of the ejecta refuse, you would have a mirror of the message.

Chads and Chips

I am learning the rectangular, round or oval bits of punched out paper are called chads or chips (in IBM usage)

A humorous derivation of chad is “card hole aggregate debris.”

Bit Bucket

Lost computerized data would be received into a bucket, called a bit bucket. In computer jargon a bit bucket is where lost computerized data goes, by any means, be it lost in transmission, or a computer crash.

The errant byte, having failed the parity test, is unceremoniously dumped into the bit bucket, the computer’s wastepaper basket.

Erik Sandberg-Diment NYT 1985

The formal name was the chad box, where the bits would be deposited.

FINO (First in, Never Out) or FISH (First in, Still Here) are humorous computer scheduling of the same concept.

FINO works by withholding all scheduled tasks permanently. No matter how many tasks are scheduled at any time, no task ever actually takes place.

A similar concept is Write-Only Memory, “a form of computer memory into which information can be stored but never, ever retrieved.”

Cards

The invention of punched cards and data storage via punched holes was developed independently on several occasions during the modern period.

Bastile Bouchon in 1725 developed the control of the loom through punched holes in paper tape, which was improved by Vaucanson and in 1804 with Jacquard demonstrating the chained punch cards as a means of controlling the loom operation. The cards held the instructions for raising and lowering the warp (shedding) and selecting the shuttle for a single pass.

Babbage proposed the use of number cards pierced with certain holes. There is no evidence he built a practical example.

In 1881 Jules Carpentier developed a method of recording and playing back musical performances on a harmonium using punched cards.

In the end of the 1800s Herman Hollerith created a method for recording data on a medium that could then be read by a machine, which was used for the 1890s US census. The same tech was used on the railroads to note the ticketholder and reduce fraud.

Hollerith founded the Tabulating Machine Company, which later became the International Business Machines Corporation (IBM) in 1924.

“By 1937… IBM had 32 presses at work in Endicott, N.Y., printing, cutting and stacking five to 10 million punched cards every day.”

Key Punch

A device for precisely punching holes into stiff paper cards at specific locations as determined by keys struck by a human operator.

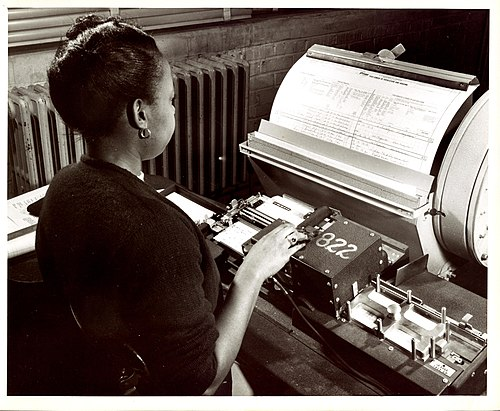

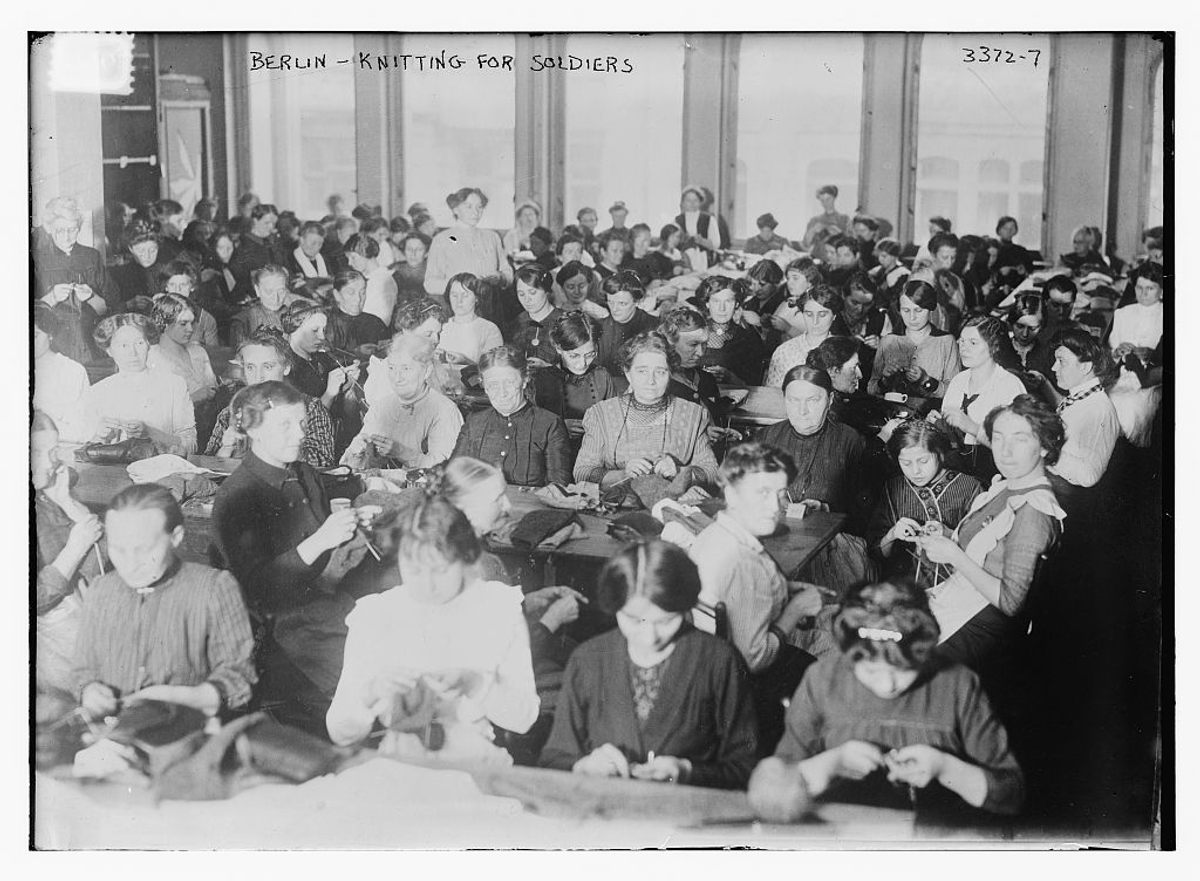

In many data processing applications, the punched cards were verified by keying exactly the same data a second time, checking to see if the second keying and the punched data were the same (known as two pass verification). There was a great demand for keypunch operators, usually women, who worked full-time on keypunch and verifier machines, often in large keypunch departments with dozens or hundreds of other operators, all performing data input.

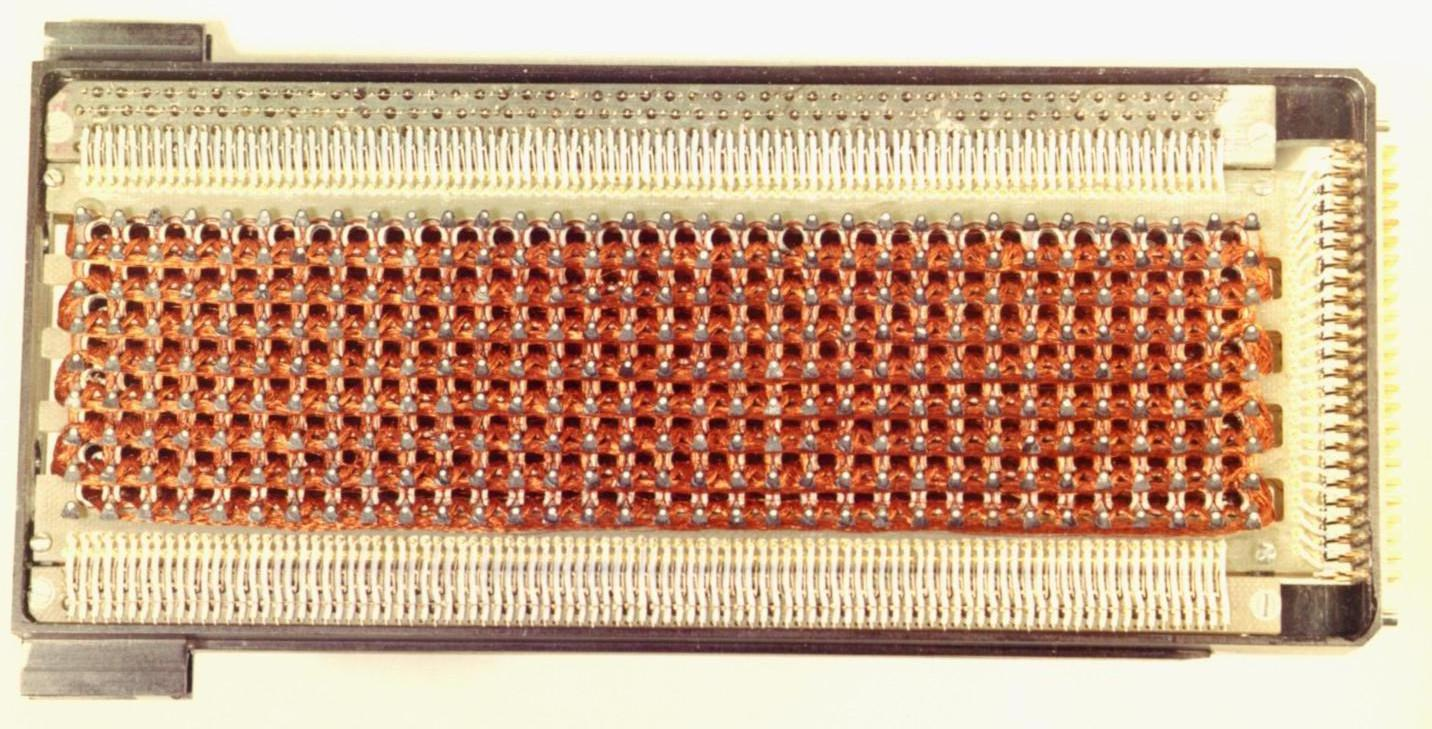

Core Rope Memory

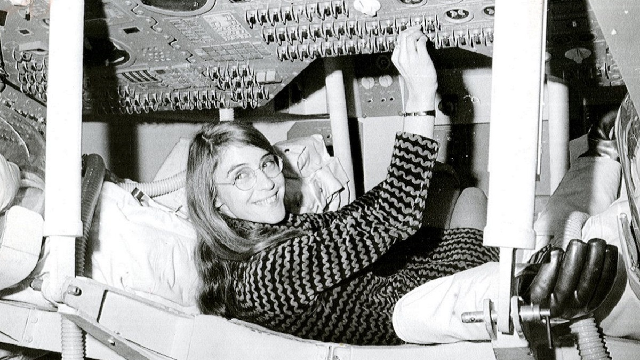

The UNIVAC I and II used this type of read-only memory. The software was written by programmers at MIT Instrument Lab and was woven into core rope memory by females workers in factories. Some programmers nicknamed the finished product LOL memory, for Little Old Lady Memory.

In Engineers were only allowed to store about 72 kilobytes of memory into the Apollo Guidance Computer, and they were only allowed space for one computer. So they needed to hardwire their programs and coding so it would not be lost if power was lost. Because of these constraints, they devised the rope memory to create physical distinctions of 1s and 0s, binary.

The process to weave the software into the ropes was so tedious and slow, it would easily take months to create just one program. To keep things moving, NASA relied heavily on, women to get the job done. Most of this impossibly important weaving work was carried out by women working in Raytheon factories, joining rank with the many female engineers and mathematicians who would help NASA eventually get to the moon.

Space age needleworker ‘weaves’ core rope memory for guidance computers used in Apollo missions. Memory modules will permanently store mission profile data on which critical maneuvers in space are based. Core rope memories are fabricated by passing needle-like, hollow rod containing a length of fine wire through cores in the module frame. Module frame is moved automatically by computer-controlled machinery to position proper cores for weaving operation.

For the read-only memory, the cores were threaded with a series of wires. If a wire passed through the core it sensed a binary one, and if the wire bypassed the core, a binary zero. The cores were laid out in a long sequence, with the wires snaking through them—the assembly was called a core rope.

Weaving the rope was a tedious process. The programs were developed on a large computer located at the MIT Lab, then translated into a code and punched on to perforated tape. This was then fed into a machine that positioned the cores for proper threading. Most of the employees who threaded the ropes were women, chosen for their manual dexterity. It is not hard to see that getting the programs right was a high priority. Once the ropes were woven it was very difficult and time-consuming to identify and fix an error.

Link to originalMargaret Hamilton

Was nicknamed “Rope Mother”

Ixchel and indumentaria maya

In Mayan mythology, the goddess Ixchel, the grandmother of the moon, taught the first woman how to weave at the beginning of time. Since then Mayan weaving traditions have been handed down from mothers to daughters, evolving a wide of array of designs.

Discrepancy

There seems to be a discrepancy with this information and the wikipedia entry.

In the past, it was common to take Ix Chel as the Yucatec name of the moon goddess because of a shared association with human fertility and procreation. The identification is questionable, however, since (1) colonial and ethnographical sources provide no direct evidence to show that Ixchel was a moon goddess and (2) the Classic Maya moon goddess, identifiable through her crescent, is invariably represented as a fertile young woman. Moreover, fertility and procreation are as important to an aged midwife as to a young mother, albeit in different ways.

For centuries weaving has been a form of a resistance. Spanish priests and authorities colonizing the land that is now Guatemala burned Maya books and destroyed cultural artefacts. Using a hidden language of symbols and colors, Maya women documented and preserved stories and culture in their textiles. Weavers are essential for the survival of Maya culture.

Traditional handwoven clothing is called indumentaria maya.

The backstrap loom: to weave, the top rod of the loom is tied to a tree or post while the bottom rod is attached to a strap that wraps around the base of the weaver’s lower back. The weaver leans into the strap to create tension and hold the loom in place while she weaves, passing the weft thread back and forth between the warp threads.

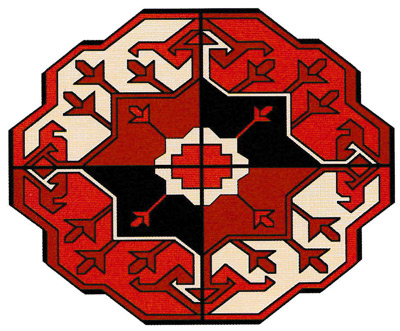

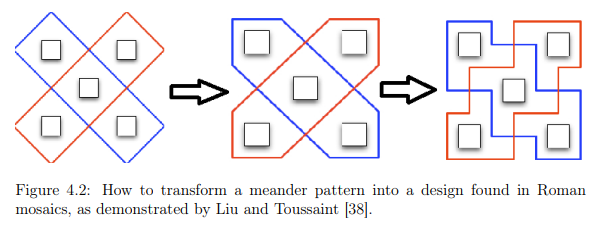

Algorithmic Complexity In Textile Patterns Notes

Algorithmic Complexity In Textile Patterns

created 2025-06-27, & modified,

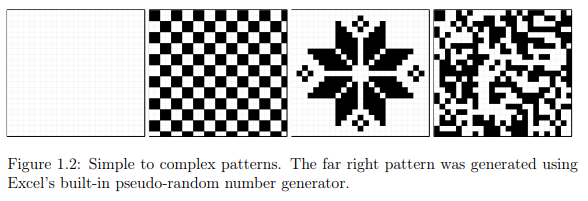

=this.modifiedAlgorithmic Complexity, also called Kolmogorov Complexity motivates the use of techniques to approximate the complexity of objects and measure the similarity between them. This paper explores the application of these methods to patterns in textiles.

Turing machines can be simulated by knitting. Approximations of algorithmic complexity indicate that there may be a way to distinguish meaningful information from arbitrarily populated matrices. The Turkmen tribes were nomadic people with a social structure that allowed woven ornaments to change independently of one another over time.

Introduction

Given an grid where each cell can take on one of two colors there are ways of coloring the grid.

There are similar motifs amongst abstract patterns, such as triangles along with symmetry and repetition. They are easily expressed in small programs.

Thought

There is a notion expressed about “ a range of complexity” of the patterns, where there is an “appealing sweet spot between blank space and noise-type chaos” that resembles Computational Aesthetics

The Mysteries of the Turkmen and their Textiles

In carpet ornaments, in combinations of colors, that have come to us over the threshold of centuries and millennia, there resound different melodic echoes of artistic creativity of the past that have stood firm against the pressure of inexorable all-destroying time. -N. Burdukov, 1904

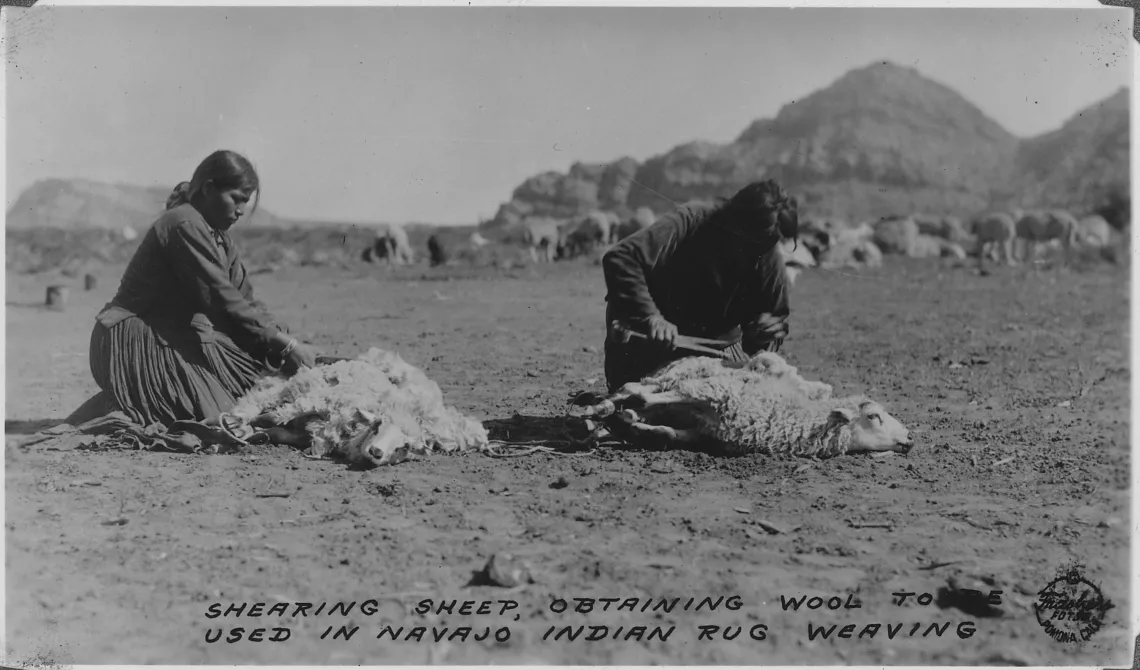

Weaving was a well-established tradition among Turkmen. The rugs covering the floors of the yurts, bags for storage and decorative items were all woven on portable looms. The sheep were sheered in spring and autumn, supplying large quantities of wool.

Weaving was strictly done by women, with skills and designs being passed from mother to daughter. Being a skilled weaver gave her a standing in her tribe. Because patterns were not written or with diagrams small mutations that occurred in patterns would be independent of changes occurring elsewhere. When tribes split, the women carried the patterns with them.

In information theory, one considers problems involving signals transmitted over noisy channels. The repeated transmission of ornaments from mother to daughter over generations is analogous but rather than a noisy channel mutations are introduced through some combination of cognitive bias, subjective preference, and the general propensity of people to doodle.

Knitting and Computability

Where are two patterns the same?

Stitchomorphism – a one-to-one function that preserves the stitches, compound stitches and turns.

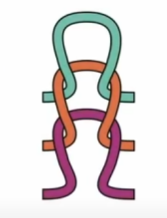

Each type of textile has its own language. The language of knitting is a finite alphabet specified in each pattern, where some stitches are composed of other stitches. Two fundamentally different atomic stitches are knit stitches, using k in patterns, and purl, represented by p.

Purl, Knit and Crochet Etymology

The word purl comes from the ancient Scots word pirl, which meant ‘twist’. Crochet is French for “a small hook”. Knit comes from the Old English word ‘cynttan’ meaning to tie in a knot.

Cellular automata Rule 110 is Turing complete, and can be knit, thus knitting can be seen as Turing Complete.

Turing Machine

Example definition used:

a Turing Machine is composed of a finite control, a tape divided into cells, a finite input written on the tape in the finite input alphabet, and those spaces that surround the finite input contain blanks. The tape extends as far as necessary in either direction. A tape head is scanning one of the tape cells. The tape head starts by scanning the leftmost input cell on the tape, then moves, possibly changing states, writing a tape symbol on the cell scanned replacing the current symbol, and moving one cell to the left or right.

Two needles serve as tape heads, called the knit head. Stitches are the counterpart of the tape. Input stitches are a finite number of knit or purled stitches and cast on stitches surround the input stitches (the counterpart of blanks in the Turing tape).

Kolmogorov Complexity

Kolmogorov complexity is uncomputable.

A string’s K(x) is the length of the shortest program that produces it.

Example

010101010101010101010101010101010101010101010101=print 01 24 timesThe more complex a string is, the longer the shortest program that produces it will be. The strings with the highest Kolmogorov complexity are called Kolmogorov random strings. There is no shorter way to produce these strings than to simply list each bit of them. As a result the shortest program that produces one of these strings is the length of the string itself plus some constant, like the number 5 to account for the inclusion of the characters in the word print.

Proof of the existence of incomprehensible strings

There are binary strings of length n. There are binary programs shorter than n. Each program only produces at most one string. Therefore at least one string is incompressible.

Invariance Theorem

Given any descriptive or programming language and a program that produces a string, the language that can produce the string with the shortest program is only off by some constant. The constant does not even depend on the string, only on the programming language.

The proof shows that a translation from one language to another can be expressed by some constant number of characters.

Patterns of one culture can be transformed into another.

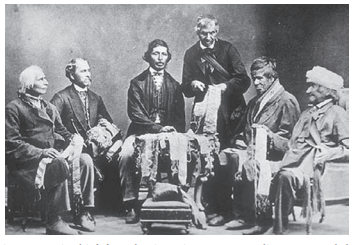

Indigenous Circuits L Nakamura

Navajo Women and the Racialization of Early Electronic Manufacture

For Haraway, the women of color workers who create the material circuits and other digital components that allow content to be created are all integrated within the “circuit” of technoculture. Their bodies become part of digital platforms by providing the human labor needed to make them. Really looking at digital media, not only seeing its images but seeing into it, into the histories of its platforms, both machinic and human, is absolutely necessary for us to understand how digital labor is configured today.

References to “nimble fingers” as a digital resource appear in account of how women of color were understood and actively recruited to work in the electronics industry.

The Navajo women actively recruited to work in the electronics of this period are associated with the digital revolution, but rarely figured in. Fairchild Semiconductor produced a racial and cultural argument for recruiting young female workers in the electronics. This was in the period of circuit assembly between 1965 and 1975. Prior to closing it employed 922 Navajos, most women. The reservations acted akin to overseas outsourcing, in that they were not subject to minimum wage laws.

Management’s standard explanation for its preference for young female workers typically rested on the idea that women’s mental and physical characteristics made them peculiarly suited to the intricacies of electrical assembly work.

The plant, which operated twenty-four hours a day, was owned by the Navajo Tribal Council and leased by Fairchild for $6,000 a month. It boasted a very low failure rate—5 percent, in contrast to rates in the twentieth percentile at other plants—and received several awards for its innovative practices.

Navajo leadership pushed the project forward, speaking of the necessity to modernize the tribe.

“It is a brilliant chapter that we write here in the dedication of this magnificent plant. It signals the real and early industrialization of the Navajo reservation. It marks the advancement of the Navajo nation from an Agrarian Nation to an Industrial Nation.”

The work itself was precise and required use of the microscope, and some could not handle it.

For example, after years of rug weaving, Indians were able to visualize complicated patterns and could, therefore, memorize complex integrated circuit designs and make subjective decisions in sorting and quality control.

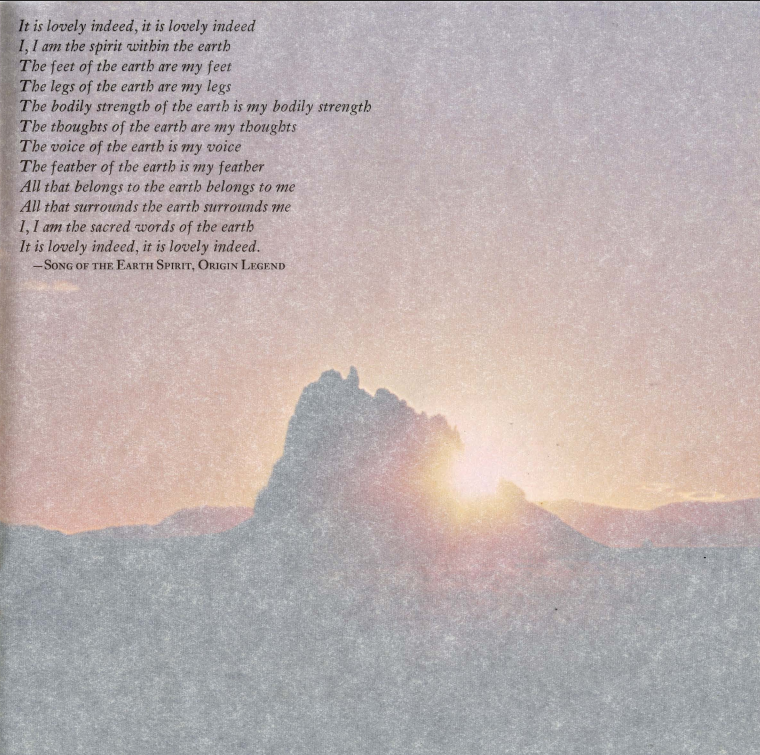

Fairchild made a brochure in 1969 celebrating the plant and it’s workers.

Inside:

The talents of the Navajo people extend beyond imagination. A Navajo woman weaves a perfectly patterned rug without ever seeing the whole design until the rug is completed. Weaving, like all Navajo arts, is done with unique imagination and craftsmanship, and it has been done that way for centuries.

From 50 initial employees, Fairchild’s Shiprock facility has grown to almost 1200 men and women, making Fairchild the nation’s largest non-government employer of American Indians. All but 24 of the 1200 are Navajo; in fact, of 33 production supervisors, 30 are Navajo.

The blending of innate Navajo skill and Semiconductor’s precision assembly techniques has made the Shiprock plant one of Fairchild’s best facilities-not just in terms of production but in quality as well. Quality becomes a necessity in the semiconductor business. Fairchild’s transistors and integrated circuits, some of which before packaging are no larger than the head of a pin, must perform to perfection in complex computers, electronic appliances, radios and televisions, and on the way to the moon as part of Apollo’s communications, guidance, and gyro systems or in instrumentation units located in various stages of the Saturn rocket. Back on earth, the success of the Shiprock facility can easily be measured in terms of growth and expansion. However, the real value of this progress lies in the creation of meaningful jobs for those who have not had jobs, jobs which will keep them in the land they love and among the people they know. And, that is success in very real terms.

The Navajo men and women working here have made my job as Plant Manager one of the most pleasant experiences of my whole life. Their adaptabilities and proven skills have shown they can do any job well, and their industriousness and desire to learn is unmatched. I hope that in the very near future every job in this plant, including mine, will be held by Navajos. The credit for our success here belongs to them.

The brochure contains a poem, with the backlit Shiprock mountain (the factory’s namesake)

The appeal to “nature” as a justification for converting “highly skilled” female cultural labor such as weaving rugs into high-tech factory work. The resemblance between the pattern of the rug depicted on the first page and the circuit is striking and uncanny. It makes the visual argument that Indian rugs are merely a different material iteration of the same pattern or aesthetic tradition found within the integrated circuit.

Depicting electronics manufacture as a high-tech version of blanket weaving served two goals

- it permitted the incursion of factories into Indian reservations

- it blurred the lines between wage labor and culturally-creative labor

The argument that Navajo women were good at their assembly jobs because they were good blanket weavers and jewelry makers appears throughout contemporary accounts of the plant.

In positioning them as creative class of workers they are aligned with the personal creative freedom, and are happy because they are creatively fulfilled, not just well paid.

“By the mid-1970s, reports of chemical exposures among production workers had begun to surface” in San Jose, California.31 Given the already high rates of pollution on the reservation from the extraction of resources such as uranium, gas, coal, and oil, semiconductor manufacture continued the ongoing practice of environmental degradation in a spot renowned for its natural beauty. Ultimately, the Navajo nation failed to benefit economically as much as it had expected from the plant and was left to deal with the detritus and its long-term consequences.

Prior beliefs about Indians as unreliable workers unsuited for modern form of labor are transformed into assertions of the positive value of “primitive” habits.

Navajo weaving had a complex cultural identity.

Navajo women did not make circuits because their brains naturally “thought” in patterns of right-angle colors and shapes. They did not make them well because they had inherent Indian virtues such as stoicism, pride in craftswomanship, or an inherent and inborn manual dexterity. And Fairchild did not employ Navajo women because of these traits. These traits were identified after the company learned about the tax incentives available to subsidize the project, the lack of unions and other employment options in the area, and the generous donation of heavy equipment given by the US government gratis as part of an incentive to develop “light industry” as an “occupational education” for Indians

The admin stated future developments would include increased opportunity for Navajo but this never was to be, ad the plant closed and they moved offshore.

Denetdale reads weaving as an important “intellectual tradition,” as does Angela Haas in her essay “Wampum as Hypertext.”

Link to original

Wampum as Hypertext Angela M. Haas

We do not weave the web of life; we are merely a strand in it. Whatever we do to the web, we do to ourselves. Chief Seattle of the West Coast Duwamish, 1854

This essay traces a counter story to Western claims to the origins of hypertext and multimedia by remembering how American Indian communities have employed wampum belts as hypertextual technologies—as wampum belts have extended human memories of inherited knowledges through interconnected, nonlinear designs and associative storage and retrieval methods—long before the “discovery” of Western hypertext.

Wampum is a small, short, tubular bead, made from quahog clam shells. The white beads are made from the inner whorl of the shell, and the purple beads come from the dark spot or “eye” of the shell.

Wampum and other material components, like fibers, sinew, hemp, string and other weaving materials have been used for ceremony and record keeping for thousands of years – by stringing beads together on individual strands and weaving them into belts.

Wampum strings and belts served to engender further diplomatic relations, and their presentation was a gesture that required reciprocity on the part of the recipient. Consequently, accepting a gift of wampum meant that the recipient accepted its implied message and responsibility.

Wampum records are maintained by regularly revisiting and reading them through community memory and performance.

Brief Western history of hypertext, with Bush’s Memex and Ted Nelson’s Xanadu, a global hypertext network that would “make all published information available to everyone and to enable anyone to freely recombine any and all documents and add their own textual content”

To explain, “digital” refers to our fingers, our digits, one of the primary ways (along with our ears and eyes) through which we make sense of the world and with which we write into the world. All writing is digital—digitalis in Latin, which typically denotes “of or relating to the fingers or toes” or a “coding of information.”

Wampum communicates visually via contrasting in dark and light beads, and meaning is inscribed in the patterns. Besides encoding information, the technologies employ systems of nodes and links that form structures via associating indexing.

Hypertext theory considers how various arrangements of nodes and links express meaning and how these arrangements are reflected in the user interface. Hypertext theory classifies these arrangements of nodes and links into various kinds of hierarchical and non-hierarchical structures, often called “information structures.”

In order to retrieve the encoded communication, an individual must be a part of the community with the cultural context for accurate retrieval of that information. The messages are spoken and woven into the wampum, and those messages are repeated each time an individual (re)presents the material rhetoric, or wampum hypertext, to the community.

Reading wampum requires an understanding of the layered meaning in the wampum

telling of stories spoken by the [condolence ceremony] wampum: stories of rekindling the fire “to bind us close”; of grave sorrow for the dead chief; of wiping away any bad blood between the two sides; of sharing the same bowl to eat together; of dispelling the clouds and restoring the sun that shines truth on all peoples.

Wampum belts are not only crafted with memories, but also “read” by memory.

African Folklore

African Folklore - Text and Textile

created 2025-04-24, & modified,

=this.modified

rel:QuipuThought

This is an excerpt from a book, African Folklore - An Encyclopedia — Philip M Peek & Kwesi Yankah that I sought out after finding a reference in Book of Symbols - Reflections of Archetypal Images.

It’s too involved and lengthy for a full read for me but I can find Survey of Text Etymology, Connections to Fiber, Body information for the citation.

Textile Arts and Communication

In African societies, where oral traditions take precedence over written ones, visual arts play a vital role in their functions as language.

The cloth lends itself to this function

- cloth is inherently a flat surface

- symbols can be applied, operating as a page.

- it has a rich and varied syntax.

- it comes in a variety of fibers woven in any number of ways, determined by which type of loom is used.

- cloth is pliable, portable medium

Cloth and Language

Threads are interwoven to produce cloth, much like words are interconnected to create syntax.

Language involves the building of written symbols or sounds to communicate an idea. Similarly, weaving requires the gradual addition of weft-threads to the warp as the process progresses. And, just as warp threads interconnect with those of the weft, words interrelate to make up the syntax of a sentence

The Dogon of Mali are among a number of African cultures that readily acknowledge the existence of speech in cloth.

They would say that “to be nude (that is, without cloth) is to be without speech.” The Dogon word for cloth, soy, even has its roots in the word so, their word for the speech of their creator god, Nommo.

The Dogon also equate the weaving process to the nature of language, believing that the threads on their loom interconnect to produce fabric just as words are combined to make speech.

They, like many groups throughout West Africa, weave on a horizontal, foot-treadle loom that produces a long, narrow strip of cloth. The Dogon claim that speech came about through weaving on such a loom. They refer to the entire loom apparatus as so ke ru, meaning “secret speech,” and equate its individual components to the physiology of an individual’s speech mechanism. For example, the reed is equated to teeth, the shuttle to the tongue (because of its constant back-and-forth motion inside the mouth) and the heddles to the uvula that rise and fall like the words themselves. Even the creaking sound of the loom during the weaving process itself is likened to the sound of the first manifestation of the word from the creator.

Dogon cloth design generally consists of white and indigo checks, either uniform or varied in size. The color and design elements in the cloth carry or connote a specific meaning. For example, the white characterizes truth and the speech of the creator god, whereas the black refers to falsehood, obscurity, and the secret speech of male initiates. The check designs refer to the cultivated field (which resembles such a configuration), the white checks being fields on the plains (i.e., easy to cultivate), and the black ones being those of the plateau, where cultivation is difficult. In sum, cloth and its production for the Dogon is a metaphorical expression of their worldview, a view that encompasses the dichotomies of village/bush, plant/animal, daily/ritual, male/female.

Cloth as Written Text

Just as cloth is used as a kind of surrogate for speech, it functions as a surface onto which words and word-derived imagery are applied.

Islamic traditions throughout North Africa produce cloths with words encoded in them. One North African type, called tiraz, has prayers or praises to rulers woven into the cloth itself. Indeed, in some cultures, such as those of Algeria, the very name for weaver (reggam) has its roots in a word meaning to write.

Link to original

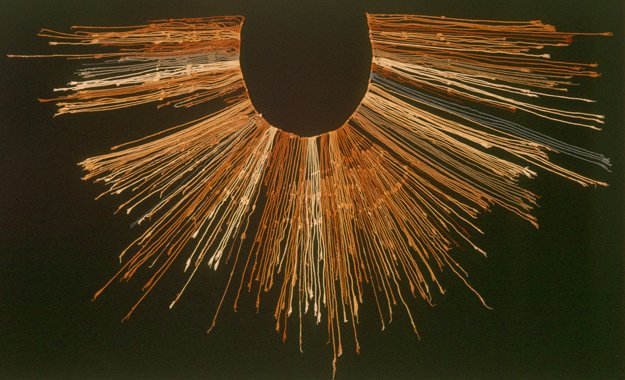

Quipu

created 2024-07-03, & modified,

=this.modifiedUnravelling an Ancient Code Written in Strings by Professor Sabine Hyland

When Sabine was granted access to the quipu they were hidden in secret areas under sacristy in churches. Now they’ve been pulled back into deeper hidden recesses to avoid destruction. Many villages appear to have their own relic, and follow this pattern of retreat upon threatening. They have allowed certain researchers like Sabine to document and thus provide cultural weight that would preserve their spaces as modernity encroaches and children move to places like Lima.

Often nobody can read the Quipu. They are popularly seen as recording devices, but there are traits of logosyllabic writing and certain Quipu are remembered as epistolary, documentation of warfare.

They appear to be more than databases, but “no specific Quipu has been reliably identified as a narrative text.

This is what I find interesting, the possibly they have this record which is passed on through generations and is currently indecipherable but now woven into myth and narrative and taken on that meaning. Not saying this is the case. I’m wondering if the documents have taken on this new light, where they are interfaced with myth due to that gap in understanding.

To them, “the cords have their own sentience”, there’s an interlude where her entry to the village coincided with appearance of native herd, which they associated. The cords are woven with the furs of different native animals. Each of these animals provide symbolic meaning to deciphering the text. Feeling these differences in the hand is critical to understanding.

Modern locals have used a style of Quipu in funerary practices. They encode prayers. All relatives come together in grieving to construct a Quipu to be wrapped around the deceased.

Spanish destroyed Incan record, attempting to replace writing and numeral systems. Deciphering Quipu could provide access to primary records. Quipu were also seen as a form of idolatry, and destroyed hence their current clandestine status.

Many Quipu now have been placed in Museums and thus distanced from their culture and the groups who would be able to provide history and meaningful association to them. The people here are physically removed from their historical language. They show signs of edits. Kinks remain where places were once knotted, as if records were cleared at the end of year. These were also communal communication devices. Quipus would be worn, wrapped around head, chest. Buried with a boy wrapped on chest.

Twisted Cords

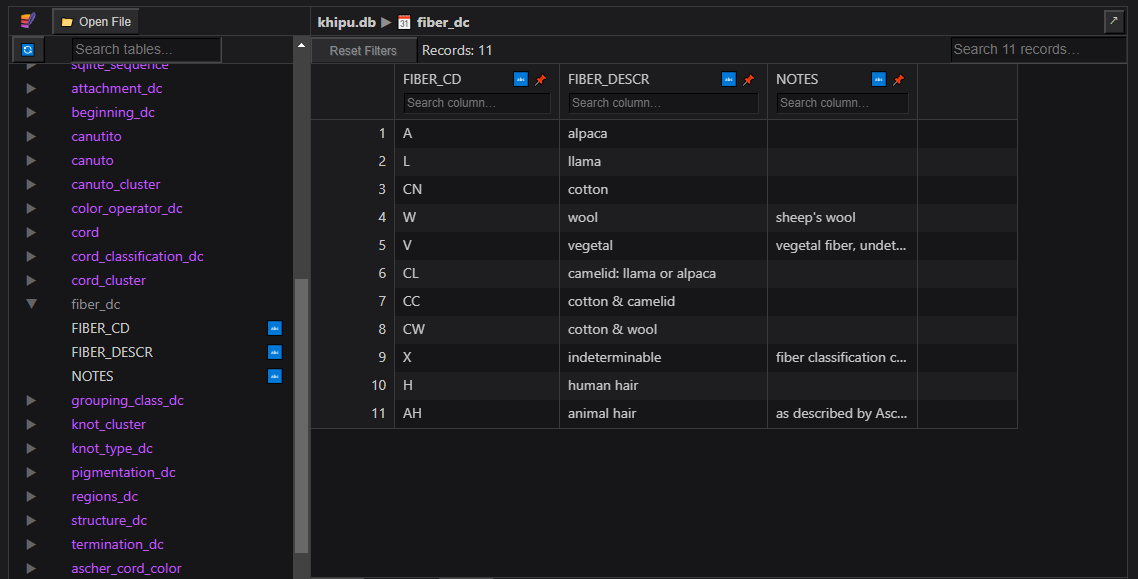

Analysis of the khipus reveals that they contain 95 different symbols, a quantity within the range of logosyllabic writing systems, and notably more symbols than in regional accounting khipus. Virtually all extant khipus are conserved in university, museum and private collections Evidence suggests that Andeans composed khipu epistles during the rebellions to ensure secrecy and affirm cultural legitimacy Inka runners, known as “chasquis”, carried khipus as letters during the Inka period Colonial manuscripts in Collata’s sacred box reveal that members of this community spoke Quechua in the past, although villagers today are monolingual Spanish speakers. Therefore, if the symbols of the Collata khipus had any link to spoken language, the language would have been Quechua, not Jaqaru or Kawki Each khipu commences with a multicoloured bundle, known locally as a “cayte”, which signifies both the beginning and the subject matter of each khipu (Hyland 2016). Khipu B’s cayte (3.8cm long) consists of a tuft of bright red deer hair wrapped with light brown vicuña threads.

Village authorities insisted on handling the khipus without gloves to feel the fibre differences Two senior herders assigned to assist me identified the animal fibres of the pendant cords (in order of decreasing frequency): vicuña, alpaca, guanaco, llama, deer, and vizcacha. The herders insisted that the fibre type conveyed meaning, stating that khipus represented “a language of animals”. Ply direction has been shown to be a semiotic feature signifying binary oppositions on khipus This explains the pun/rebus connection. Very interesting.

Modern catechetical “cakes” represent prayers through items set into clay using rebuses. For example, a tuft of llama wool can represent the Spanish “se llaman” — “they are called” — because of the similarity between “llama” and “llaman” Likewise, a blade of “ichu” grass often signifies “Jesús” because of the similarity of sounds This proposed decipherment suggests that khipu pendants may possess standard syllabic values My layman understanding here is that there was this cultural/custom shared mnemonic system, obviously lost to time which would provide access to deeper understanding of the corded documents. It’s unsure if these modern Quipus represent a direct link To the methods of the incan ones, or are a modern innovation. Musems = 800 Quipus, but once 100,000s Some forgeries seem to exist in museums and could also be in the datasets.

Modern catechetical “cakes” represent prayers through items set into clay using rebuses. For example, a tuft of llama wool can represent the Spanish “se llaman” — “they are called” — because of the similarity between “llama” and “llaman”

SQLite

Examining the open database of quipus.

A seeming database system of animal hairs, cloth and metal later taking on this air of an encoded myth and a language of animals, then being stored in a computer db. Wow.

This open-source digital repository stores the most up-to-date data and metadata on extant Inka-style khipus from archaeological sites in the Andes, as well as museums around the world. Inka khipus were unique pre-Columbian, Andean recording devices that used three-dimensional signs — primarily knots, cords, and colors — as symbols functionally akin to those of early writing systems in other cultures. Spanish chronicles, as well as contemporary khipu studies indicate that the Inka used khipus to record everything from accounting records to historical narratives. The khipu recording system remains undeciphered, however. The purpose of this repository is to enable computational khipu research and Inka khipu decipherment efforts.

Quipu Course

[link](https://courses.csail.mit.edu/iap/khipu/)

Link to originalStudents will divide into groups. Each group will develop their own way of “writing with rope”—developing a written language like quipu. The method can use all or only some of what we know about actual quipu (e.g., the different types of knots used). These languages will be interesting in their own right, but they may also shed light into plausible approaches taken by the Incas. Each group will also work on breaking the code developed by another group. This will give us experience in recognizing different types of codes, and ultimately in decoding actual quipu.

Mathematics of the Incas - Code of the Quipu

This book is about an artifact that became the medium for Expression in a major civilization.

This book is about an artifact that became the medium for Expression in a major civilization.

“One of the three brothers had a golden sling, and with it he could throw a stone up to the sky; it would almost touch the clouds” - this is an Incan origin story → it is spoken in Quechua, recorded into Spanish and then translated into English

A quipu is a collection of cords with knots tied into them.

In earlier times, when the Inca’s moved in upon an area, a census was taken and the results were put on quipus. The output of gold mines, the composition of work forces, the amount and kinds of tribute, the contents of the storehouses - were all recorded on Quipus (according to Cieza)

Cieza died young, 1554. In a portion of the will devoted to saying masses, he requests hundreds for himself and his family and others. Eight masses should be said for a women called Ana.

Quipus have levels.

Main cord with pendant chords, which can be looped. subsidiaries can hang off pendants cords can hang on top, a top cord. Dangling cords can hang off the end, almost like a credits they provide a sequence, a before and after can be applied from their introduction. terms like above and below become applicable.

Spaces between cords are also part of the intentional overall construction

Color is fundamental to the symbolic system of the quipu. Color coding, that is, using colors to represent something other than themselves is a familiar idea. Lobsterman buoys are colored to distinguish between the fisherman.

The knots are base 10 system and would mark numbers, 1 2 3 = 1 knot space 2 knot space 3 knot space.

Native terms

- huaca, an object that is sacred

- ayllu - a fundamental social unit beyond the family. a village might be composed of several ayllu

The quipumaker - compared to sumerian tablets, the writing space is nonlinear. The nonlinerarity is a consequence of the soft materials he used. A group of string occupy a space that has no definite orientation; as the quipumaker connected strings to each other, the space became defined by the points where the strings were attached (these did not follow any strict left to right or right to left sequence), especially with the added dimension of color.

We do not know how many quipus still exist below the ground, in graves. No two quipumakers write alike, and also differ in terms of legibility, with no two making knots the same.

It is impossible to say that a certain quipu is a record of a certain census, or a song in praise of the sapa Inca.

Quipu (General Knowledge)

Quipus held information, decipherable by officials called quipucamayocs, classified in various categories, narrated from the most important to the least important category, according to color, number, and order.

Most information recorded on quipus consists of numbers in a decimal system. Quipus would be used to settle disputes over local payments or goods productions. The quipucamayocs could be summoned to court, where their bookkeeping was recognized as valid documentation of last payments.

Some knots, and secondary features (color etc) have been though to represent non-numerical information that has not been deciphered.

In 2011, a potential match between a Spanish colonial document and six colonial-era quipus from the same region was identified. Researchers believe this possible quipu-document match is the strongest Rosetta Stone-like connection currently known, which could offer key clues needed to unlock the full extent of the quipu code. Subsequent studies have built on the proposed quipu-document connection, suggesting that the binary manner by which cords can be attached to the main body of the six quipus may encode moiety affiliation, and, more recently, uncovering detailed Andean social structures encoded within the six quipus

It’s possible that phonetic decipherment of epistolary Quipu was influenced by introduction of European writing systems. Sabine Hyland argues, with the help of local leaders, that the names of two family lineages who received and sent quipus can be translated using phonetic references to the animal fibers and colors of the relevant quipu cords.

The exploration of Quipu as a writing system is confounded by absence of early records. Possible reasons for this apparent absence of a written language include destruction by the Spanish of all written records, or the successful concealment by the Inca peoples of those records.

Historians Edward Hyams and George Ordish claims quipus were recording devices, similar to musical notation, in that the notes on the page present basic information, and the performer would then bring those details to life

Magic The Gathering Card

SkyKnit

Janelle Smith created “Project Hilarious Disaster” which was a Neural Network trained on a series over 500 knitting instructions. She generated these instructions, which the knitting community were then instructed to knit.

“The knitting project has been a particularly fun one so far just because it ended up being a dialogue between this computer program and these knitters that went over my head in a lot of ways,” Shane told me. “The computer would spit out a whole bunch of instructions that I couldn’t read and the knitters would say, this is the funniest thing I’ve ever read.”

The patterns themselves often are “broken” and require human fixing to be physically instantiated.

This kind of “fixing” of the pattern is not unique to the neural-network-generated designs. It is merely an extreme version of a process that knitters have to follow for many kinds of patterns.

In this manner they are more akin to older patterns of the 19th century, which did not hold the hands of the knitter. Modern patterns are more explicit.

Thought

There is some similarity here with Skeletal notation and Embellished music where a skeletal form of musical composition was presented, and the the completion (embellishments) were left to the performer.

The creations of SkyKnit are fully cyborg artifacts, mixing human whimsy and intelligence with machine processing and ignorance. And the misapprehensions are, to a large extent, the point.

AI Generated Patterns

In addition to AI generated patterns (LLM or otherwise) there is a current proliferation of fake patterns, and impossible imagery.

Cuffs can appear strangely smooth, and human models distorted.

The sellers take advantage of the fact that digital projects in these storefronts have been unregulated, and receive cheap money.

Thought

Similar to my experience (pre-AI) of purchasing flowers online. The fantastic false flowers (imaginary colors) would surface first in my search. There’s a bit of Bug on Sensor here in the sense that this mimicry almost resembles the attractive function of actual flowers, but it has been distorted and digitalized.

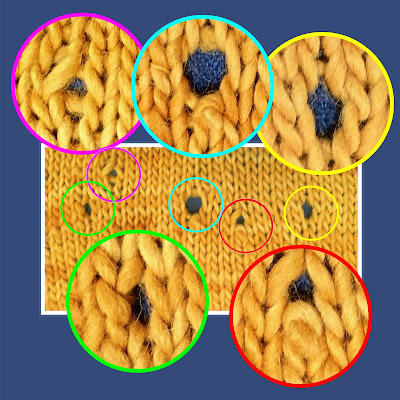

Holes in Knitting

Knitting hole origin can be distinguished.

Knitting hole origin can be distinguished.

- enlarged stitch

- dropped stitch combined with inadvertent yarn over

- inadvertent yarn over

- dropped stitch, triangular hole

- partial short row.

Molly Rinker - The Spy Who Knitted Socks

Female spies during the American Revolutionary War also used the “old women are always knitting” stereotype to their advantage.

Moly was a bartender and spy during the American Revolutionary war, known for gathering secret knowledge by overhearing British soldiers who stopped at her bar to get drunk, and then speak of their plans against the American troops. Molly would write the information on tiny slips of paper which she carefully hid in knitting yarns and dropped off a cliff. This would be intercepted by George Washington and his troops.

The socks Molly Rinker was knitting were for the rebel army of course. At the time that alone could get you locked up as a traitor. During the winter of 1777-1778 over two thousand rebel soldiers died due to exposure, disease, and starvation. Giving any form of relief to the troops was a crime. To openly knit socks for the rebels, and supposedly Mom Rinker made no secret as to where her sympathies lay, was bold with a capital B.

Steganography

Dropped stitches were used to transmit information to soldiers in WWI.

During World War I, a grandmother in Belgium knitted at her window, watching the passing trains. As one train chugged by, she made a bumpy stitch in the fabric with her two needles. Another passed, and she dropped a stitch from the fabric, making an intentional hole. Later, she would risk her life by handing the fabric to a soldier—a fellow spy in the Belgian resistance, working to defeat the occupying German force.

Phyllis Latour Doyle, a secret agent for Britain during World War II—and now, at 100, the last surviving woman who spied for the Special Operations Executive—spent the war years sneaking information to the British using knitting as a cover. She parachuted into occupied Normandy in 1944 and rode stashed bicycles to troops, chatting with German soldiers under the pretense of being helpful—then, she would return to her knitting kit, in which she hid a silk yarn ready to be filled with secret knotted messages, which she would translate using Morse Code equipment.

Unravelling Method:

“When the German authorities carefully unraveled such a sweater, the story went, they found the wool thread dotted with many knots. By marking a vertical door frame with the letters of the alphabet, spaced an inch apart, the knots could be deciphered as words by measuring the yarn along this alphabet and marking which letters the knots touched.”

Languages for 3D Industrial Knitting - Lea Albaugh

From Strange Loop Conference

Knitting is fundamentally a lot of loops (stitches) connected to one another. A single loop can be pulled, and just become string, but a loop can be connected to another loop for stability.

In knitting time flows from bottom to top, when making knitting all you’ve knit follows down according to gravity. The top row is the vulnerable one.

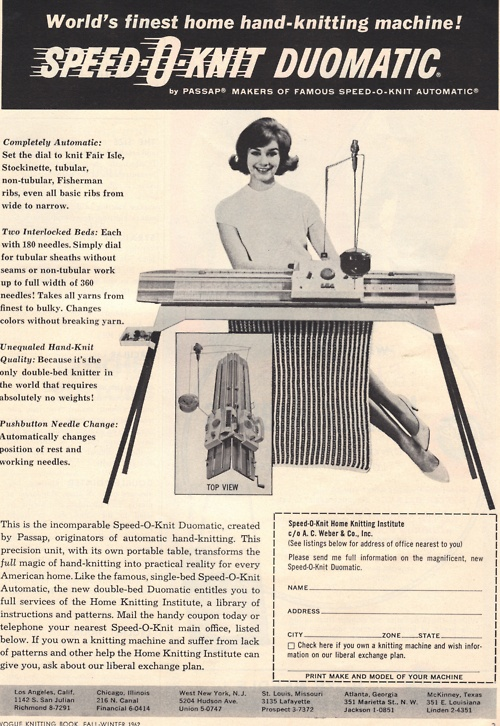

Knitting Machines have existed since 1589 with William Lee’s stocking frame at the beginning of the Industrial revolution.  After an industry period, the use of these tools diffused into home use. Flat knitting style of machines became marketed as a home tool.

After an industry period, the use of these tools diffused into home use. Flat knitting style of machines became marketed as a home tool.

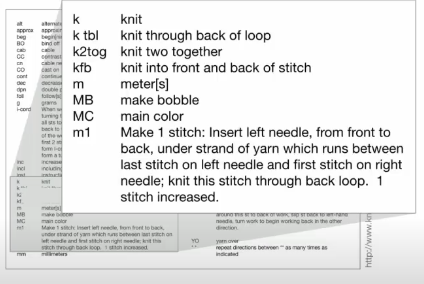

Probably the most common language for hand knitting is what a lot of people call Knitspeak, and it’s kind of a loose collection of commonly-used abbreviations and some light expectations about syntax. You can think about it as a lot like a cooking recipe, and just like a recipe, knitspeak focuses on operations, not necessarily on results.

Most patterns will start with a standard glossary.

Charts are also used in combination with the lingo.

Charts are also used in combination with the lingo.

Demonstration of the Nancy library (Nancy is another name for the knitting frame.)

I first started working on this library when I was making these little modular stuffed creatures and I designed it with kind of an Exquisite Corpse approach. So if you’ve played the dadaist game Exquisite Corpse you know you kind of like draw some lines on some paper and it doesn’t really matter what the lines do between these connecting lines; as long as everything ends up back at the connecting lines, you’re golden.

Programming mechanics in knitted materials, stitch by stitch

Knitting has long been regarded as an art that turns natural fibers into garments.

Thought

Natural → ordered garments. Natural language to patterned?

Likewise, knitted textiles can harvest energy from human movement and even store energy as wearable supercapacitors,

Knitting turns yarn, a 1D material, into a 2D fabric that is flexible, durable, and can be patterned to adopt a wide range of 3D geometries. Like other mechanical metamaterials, the elasticity of knitted fabrics is an emergent property of the local stitch topology and pattern that cannot solely be attributed to the yarn itself. Thus, knitting can be viewed as an additive manufacturing technique that allows for stitch-by-stitch programming of elastic properties and has applications in many fields ranging from soft robotics and wearable electronics to engineered tissue and architected materials. However, predicting these mechanical properties based on the stitch type remains elusive. Here we untangle the relationship between changes in stitch topology and emergent elasticity in several types of knitted fabrics. We combine experiment and simulation to construct a constitutive model for the nonlinear bulk response of these fabrics. This model serves as a basis for composite fabrics with bespoke mechanical properties, which crucially do not depend on the constituent yarn.

Notes from “Weaving Worlds (2007)” Documentary

Somewhere in the very core of my being I want to weave rugs.

All the tools, the batten, the carding brush, the spindle and comb, have life-giving names. They all have sacred prayers and songs. Those rugs are machine-made. There are no thoughts or prayers in those.

When you run wool through the warp, you invest personal thoughts and feelings. That’s how how claim our own designs. We copied no one.

A woman purchases thread from her, to sell at a distant market

I know how to figure out without calculator because I count my strings all the time when I weave.

Oh so it’s the same thing.

Someday the battery’s going to be dead and you think her brain is working.

First Phase Navajo Blanket

During the film Navajo blankets are brought to market, in attempts to appeal to the “Anglo” buyers. Through this I learn of First Phase Blankets.

Worn around the shoulders like large, banded shawls, Navajo chief’s blankets were expensive garments, commanding as much as one hundred buffalo hides or twenty horses in trade. The term “chief blanket” came into use because only the highest-ranking members of the Plains tribes had the resources necessary to trade for these blankets.

The original were simple in design, later phases developed new priorities and attempts to appeal

Between 1800 and 1840, Navajo chief’s blankets featured simple, horizontal striped patterns in blue, brown, and white handspun yarns. After the introduction of rectangular, target designs during the 1840s, and the subsequent introduction of concentric diamonds during the 1850s, Navajo chief’s blankets with no designs came to be known as “first phases.” Chief’s blankets with rectangular designs came to be known as “second phases,” and chief’s blankets with concentric diamonds came to be known as “third phases.”

While first phase chief’s blankets were popular among Plains Indians, 19th century Anglo-Americans preferred the more colorful and decorative second and third phases to the stark horizontal bands of the first phase. As a result of that preference, very few first phases were collected by Anglo-Americans until the late 19th century, when their beauty and rarity were more fully appreciated.

It is a return to an earlier state, a memory

Its colors speak of a time when complexity and decoration were of less importance than contemplation and restraint.