created, $=dv.current().file.ctime & modified, =this.modified

tags:textbooksy2024

Purpose?

Thinking here how the body is found in literature. I like the idea of viewing the body as a book, or the book as a body or the world as a book etc.

A Corpus of text, the body of text

Corpus = late Middle English (denoting a human or animal body): from Latin, literally ‘body’. corpus (sense 1) dates from the early 18th century.

When you are analyzing literature, you might wonder why the saying can’t just be understood simply. Why does (generally) a poet force us to analyze the text to understand what is being said.

I can say “I love you” to someone, or I can compose poem where I relate my love shaping of the river of water that means my love to you (etc etc). Does “I love you” hold within it all of these rivers and sonnets? is that true? is that why that thought of it being shared has weight

An aged man is but a paltry thing, A tattered coat upon a unless clap its hands and sing, and louder sing For every tatter in its mortal dress …

It’s like to understand we have to convolute, and it alienates. the artistic choice of pressing into strangeness. There’s a symbolic challenge. It’s like a challenge to meet on the same space, mentally. Not just a general, public space.

And flirting has an aspect of this. It’s indirect. There’s romance but allowing for plausible deniability. Not a direct “I love you,” but the rivers etc yada yada

With love I sometimes struggle to be direct. IT seems unbearable to do, and I am trying to find out why.

And so love and poems can sometimes be tied.

Literary interpretation—the elucidation of symbolic meaning in literature—involves a logic and method that can be readily learned by anyone who has had some experience reading poems and plays and novels, but that may at first encounter seem puzzling or abstruse. To students in the first weeks Of an introductory literature course, asked to analyze a or short story in a manner entirely new to them, and to perceive and discuss meanings they did not previously to exist, the very nature of interpretation may seem to be at issue. This is a point at which one is likely to ask certain questions— why should we analyze literature? why can’t we just read it? why do we have to discuss symbolic meaning?—that deserve answers. One way of seeing literary interpretation in is to observe that we live in a world organized by symbolic meanings, and one that demands continuous interpretation. We turn on the

The manicule

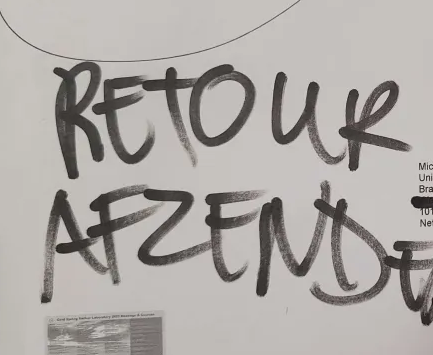

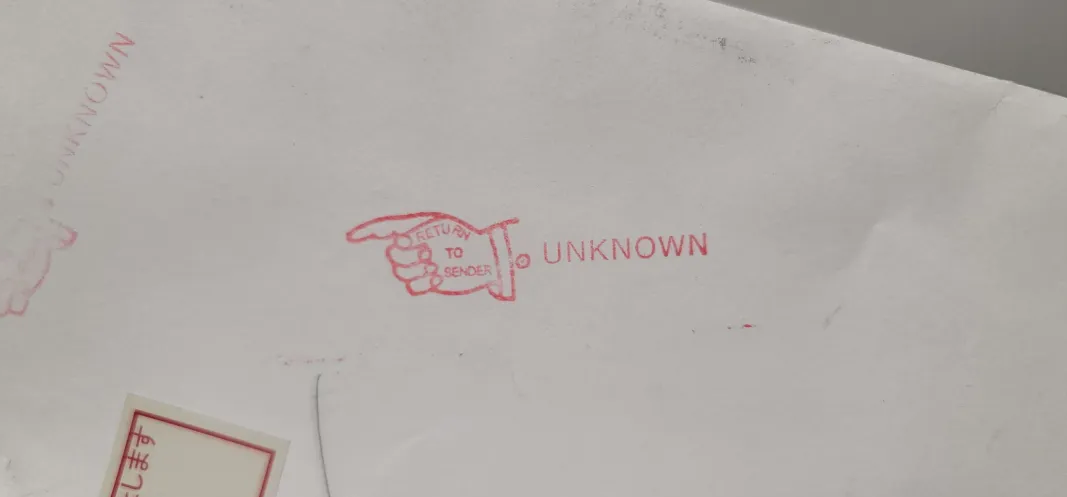

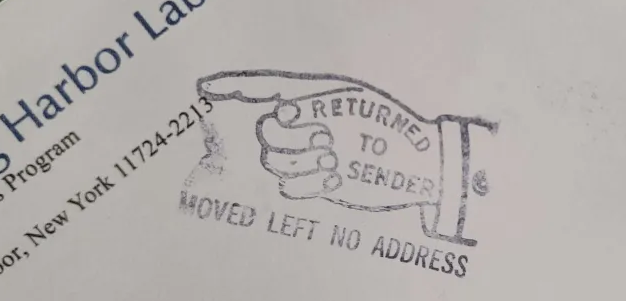

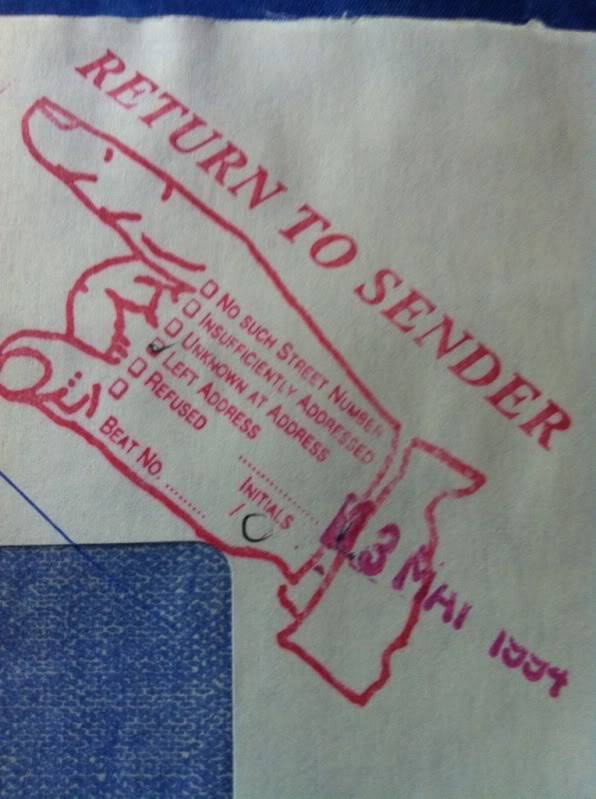

We send out a lot of mailing at work. Because the data is sometimes dated and people shift institutions we’ll also get return to senders of this mail.

I was fascinated by the variations of various country’s stamps and noticed this pointing finger motif on many of the specimen.

- There’s a button near the cuff on many of them, pointing to a universal glyph

- There’s also some weight to the finger that causes it to bend. I examined my hand pointing and realized this was also present in me, but not to this extent. Basically, mimicking the glyph exactly feels slightly unnatural to a gestural point.

There were also some terrifying and beefy variants like below.

What I had learned was this is called a manicule and it lead me on a long path of studying this.

- the earliest noted “manicules” are from doomsday book

- alternate obscure names for manicules, indicationum, indicule, mutton fist, bishop’s fist, hand direction

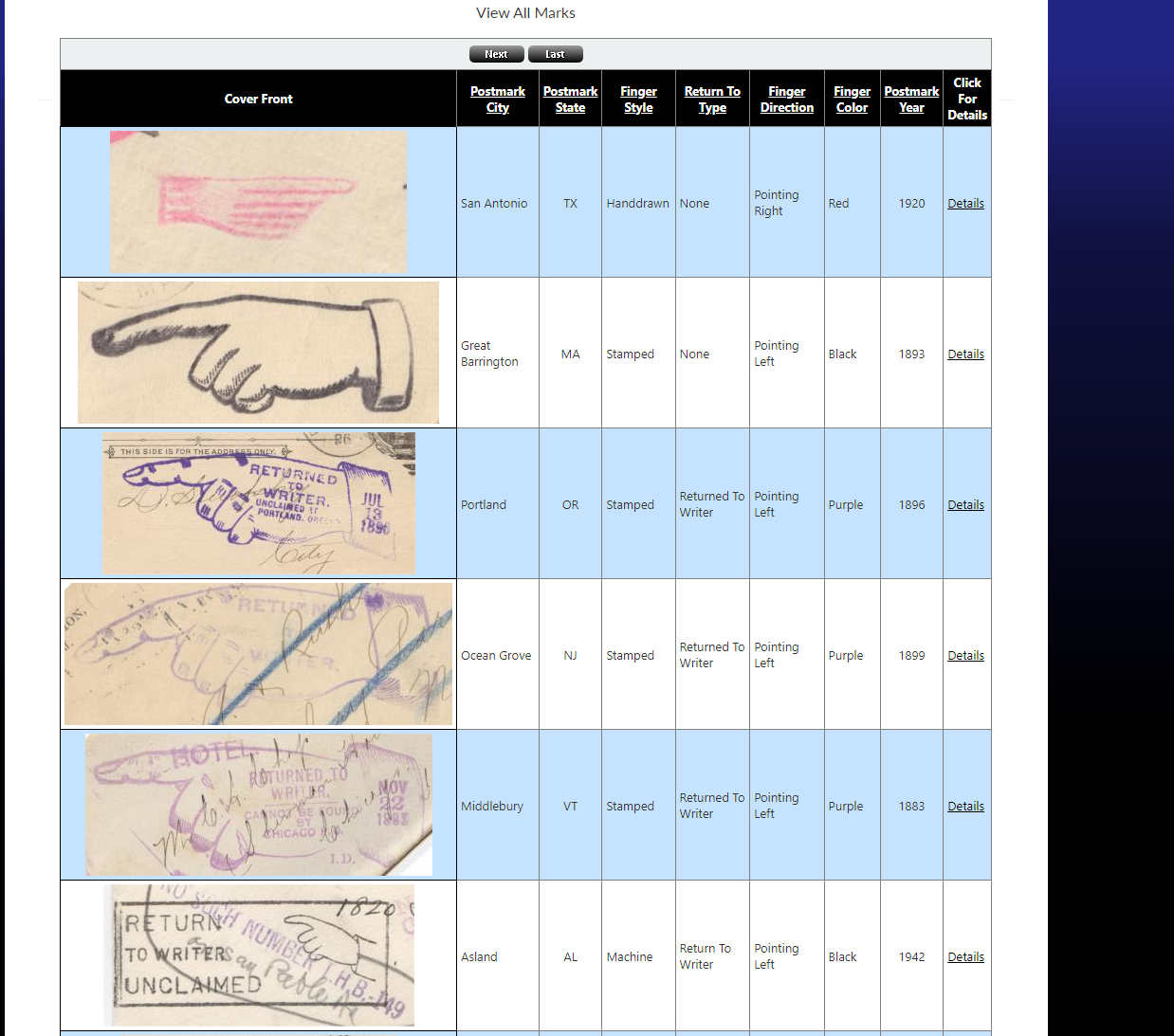

I discovered there is a database of these pointing hands here

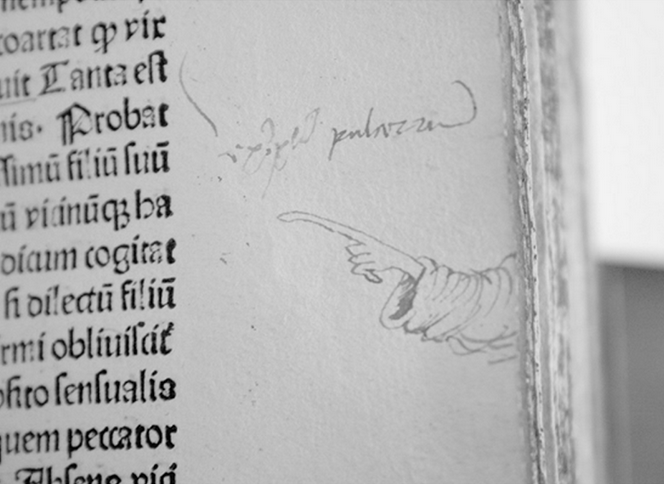

You can see older specimen like this

It’s funny how I’m seeing conflicting messaging say this symbol has died, when it’s kind of on every hyperlink hover. It probably has appeared multiple times as this passage is read in cursor form.

Reading notes

“The history of the hand in relation to the book is above all the history of the index (in the multiple senses of that word).” —Peter Stallybrass, “Navigating the Book” (1998)

Manicule study appealed to me because it feels like the human being embodied into the book.

When you are looking at the book, you are looking at the not only words but your hands are present in frame. It has that hidden in plain sight aspect that I like, that apprehends you when you realize it.

But I found myself asking: why did readers like Parker take the trouble to stop and sketch a pointing hand when a simple line would have been faster, easier, and more precise?

Gestures, like words, belong to an ephemeral world. Usually they do not leave any traces for historians.

Is this true?

Diconson put it, “the hand and meaning ever are ally’de.”

other related etymologies → manual, manipulate

“while the tongue is vulnerable to distortion and deceit, the gestures of the hand will always be “the truest copie of the Minde.”

The text inscribed on the unusually capacious cuff indicates the nature of the reader’s interest.

The Postal Service continues to use it:

Hasler was particularly interested in their use in commercial and industrial settings, and they come to play a crucial role in the visual vocabulary of advertising—as well as in public signage (most obviously in “fingerposts”), and in a wide range of official documents (including the “Return to Sender” stamp used by the US Postal Service).

In 1980, Allen Kay developed SmallTalk, the first commercial object-oriented programming language and probably the first to use a hand-shaped cursor, for the Xerox Star, the immediate forerunner to Apple’s Lisa, which would evolve into the Macintosh. And in 1981, Ben Schneiderman coined the phrase “direct manipulation” to describe the developers’ goal of replacing typed line commands with visual objects that could be handled in ways familiar from the real, physical world. Both Kay and Schneiderman were in close contact with the field of child development, and took their inspiration from practical experiments on the ways in which children use to learn basic tools: one of their basic principles was that users should be able to “point and click.” Finally, in the early 90s, the first web browsers were designed where the cursor changes from an arrow to a hand with a pointing finger whenever there is an active link to something else; and Adobe began to use a similar hand (in its Acrobat and Photoshop applications), allowing readers to grasp a page with their virtual fingers and move it around. Again, for the basic business of ‘greeting, showing, and teaching’, the hand is the perfect Graphic User Interface

Community Manicule

I also had this idea of a community manicule. I think it’s a bad idea probably, and could be disruptive.

The idea is having this persistent indicator IRL. Random example coming off the top of my head. Like lets say you pass this door every day, and it has a bit of rug, some excess fabric that buckles and makes it difficult to close the door. Multiple people pass it every day. Perhaps this is a place for a community manicule. It would point directly at the bump in the fabric, demanding focus and address. It might be a giant sticker.

That’s the motivation. The problem is obviously it’s like pointing at something, rather than acting on it. Like a symbol of complaint. But that’s specific to this example.

I’m just wondering how our world would be shaped by having this, even a virtual version. (a tree limb hangs over a sign, people manicule it) etc

Paperscapes - Navigating Books in Early Modern Englandpaper

paper is substrate - in previous sense substrate was “to exist below”. Challenging it as something that lies passively beneath the text, it actually inflects meaning

subjectitum substration “the material part of sin, the udnerlaid subject “truth is not obvious in the surface of things, but hath a depth, being sunke and retired from us”

john gauden

“paper resists and reacts with the surface of the inked type - locally. Larger scale, paper moves - book trade, the modern libraries. it is mobile, while inert. a book read in madrid or montpellier are fundamentally the same.

paper itself modifies the state of affairs of how we read.

Idea

I need to note, a book can be decomposed, removing of a page easily. pages can also be inserted, a bookmark, a note sheet.

Umberto Eco’s vegetable memory concept for the type of memory of a book Adding an artificial page to a book as an art project. Rogue pages.

The Table of Contents and Index as altering reading navigation in early books

“to read the collection is to navigate not just the cognitive spaces of the stormy seas or rocky paths of emblems, but in the material space of and between the paper sheets which consittute the form of the book”

The index is reader-oriented. the contents page is commited to the linear structure of the codex. “not only was the reader freed from the obligation of traversing a library in order to extract fragments of “writ” they were free of reading this book in its entirety.

The ToC also refocuses and re-centers the entire codex that its supposed to transparently represent. The ToC explode the verses into a series of fragments, the index shatteres the discrete framework of each page and replaces it with themes which thread their way through the book “Death 1. 21. 45. 48. 94. 168. 184. 235”

“there are no dead metaphors, only sleeping ones. any of them, looking like death can be brought back to life by paying attention to it” dennis donoghue

Linguistically Deixis describes this indexing

In linguistics, deixis (/ˈdaɪksɪs/, /ˈdeɪksɪs/)[1] is the use of words or phrases to refer to a particular time (e.g. then), place (e.g. here), or person (e.g. you) relative to the context of the utterance

Thumb

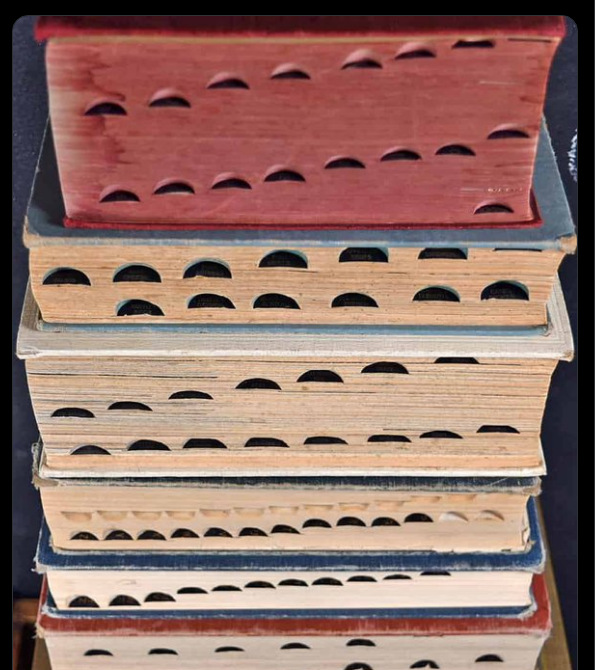

This [specialized dictionary](https://cool.culturalheritage.org/don/toc/toc1.html) is an amazing resource. I was looking for this particular type of index I recall seeing, where notches are placed in the book that fit the thumb.

Lo and behold, the thumb index

A type of INDEX which utilizes a series of rounded notches cut into the fore edge of the book. Each generally has a label bearing a letter or letters indicating the arrangement. The index proceeds from head to tail and front to back of the volume. The maximum number of thumb cuts, and therefore the number of letters represented by each, depends on the height and thickness of the book. The thumb index is used principally for Bibles and dictionaries. The cuts are usually made by a machine designed for the purpose. Also called “cut-in index.” (264 )

Manual and Manuscript

early 15c., “small service book used by a priest,” from Old French manuel “handbook” (also “plow-handle”), from Late Latin manuale “case or cover of a book, handbook,” noun use of neuter of Latin manualis “of or belonging to the hand; that can be thrown by hand,” from manus “hand, strength, power over; armed force; handwriting,” from PIE root *man- (2) “hand.” Meaning “a concise handbook” of any sort is from 1530s. The etymological sense is “small book such as may be carried in the hand or conveniently used by one hand.”

Handwriting and hands.

Manuscript and Manus.

late 16th century: from medieval Latin manuscriptus, from manu ‘by hand’ + scriptus ‘written’ (past participle of scribere ).