created, & modified, =this.modified

rel: Remember The Hand by Catherine Brown Poché of the Mind Palace, Virtual Architectures

Why I’m reading

Another part of the series in Fordham Series in Medieval Studies, after getting a lot out of Remember The Hand by Catherine Brown.

How does nonsense reflect on meaning? What are the degrees of nonsense?

The Wind in the Shell: Prolegomena to the Study of Medieval Nonsignification

The theory of signification in the West began as a theory of the oracular.

Thought

Oracular → relating to an oracle, and oracle has Latin roots in orare meaning “to speak.”

Oracular utterances are called khrēsmoí in Greek. Oracles were thought to be portals through which the gods spoke directly to people.

The word sign (semeion) first emerged int he realm of division, the technical term referring to the enigmas of the manic utterance.

Chaucer recorded his dreams. He claims to have beheld a sight: a windmill, and it was being placed under a walnut shell.

It is easily observable that noises do not remain where they arise, that as soon as they become audible in one place they are already becoming fainter there and starting to become audible somewhere else. Where, then, are all the noises going?

He asserts that just as heavy objects tend towards the lowest place possible, sounds are drawn to their most natural proper place, and somewhere in the universe is a point they all collect.

This point is the hous of Fame – a place midway between heaven, earth and the sea – a “realm of language itself.”

Clacking of a windmill

It means that a shell is capable of sheltering not only a kernel of meaning but other things as well, or at any rate one other thing in particular. And, like the shell in which it is placed, this particular thing will not be selected at random. For the windmill, too, was a familiar linguistic figure in Chaucer’s time and place: “the clacking of the windmill,” it has been observed in another context, “was commonly used to convey empty garrulity.”

In 1916 Walter Benjamin sent out an unfinished essay “On Language and Such and on the Language of Man” setting out to expose the “invalidity and emptiness” of the “bourgeois conception of language”.

Benjamin saw this conception of language is “intrinsically false.”

In order for a word to count as a word, it would have to signify something to someone, and only when such a signification is present could there be language at all. In the absence of signification, there might be raw noise, random marks, unmotivated gestures; there might be human beings relating to one another, dumbly, in passion, aggression, or indifference; there might be various sorts of things existing in the world—but there would not be language.

He is not suggesting language is random noise, but that meaning is held in an ultimate linguistic dimension, a pure language (reine Sprache) that communicates nothing at all and to no one.

“In this pure language—which no longer means or expresses anything but is, as expressionless [ausdruckslos] and creative Word, that which is meant in all languages—all information, all sense, and all intention finally encounter a stratum in which they are destined to be extinguished.”

Thought

The purely creative word, novel, is expressionless?

The encounter with such a word—belonging to a given language but not included in its lexicon, allowing no particular meaning to attach to itself and (not least) afflicting anyone who discovers it with unceasing torment—is the encounter with language as such.

It is unmistakable, in short, that linguistic nonsignification is a preoccupation of the modern era. The point goes practically without saying, in fact, though Friedrich Kittler, for one, has made it explicit: “our epoch,” he writes, is “the epoch of nonsense.”

William the Ninth, Duke of Aquitaine’s poem:

Farai un vers de dreit nien: non er de mi ni d’autra gen, non er d’amor ni de joven, ni de ren au, qu’enans fo trobatz en durmen sus un chivau.

[I’ll make a verse about absolutely nothing: it won’t be about me or about other people, it won’t be about love or about youth, nor about anything else, because it was found while asleep on a horse.]

Grammelot

This is a kind of “phonesthetic parody” or a kind of nonsensical improvised gibberish. It uses prosody along with macaronic (mixture of languages) and onomatopoeic elements to convey emotion or mimicry.

A modern form of Grammelot can be heard in the Despicable Me franchise, where the Minions speak a fictitious language; the language is made up of words borrowed from several languages, which make no cohesive sense, relying instead on tone and expression to convey the meaning.

Edgar Wind:

The process of recapturing the substance of past conversations is necessarily more complicated than the conversations themselves. A historian tracing the echo of our own debates might justly infer from the common use of such words as microbe or molecule that scientific discovery had molded our imagination; but he would be much mistaken if he assumed that a proper use of these words would always be attended by a complete technical mastery of the underlying theory. Yet, supposing the meaning of the words were lost, and a historian were trying to recover it, surely he would have to recognize that the key to the colloquial usage is in the scientific, and that his only chance of recapturing the first is to acquaint himself with the second.

Roger Bacon drew attention to a quarrel in the field of logic, the theorists of language could not agree on whether words are the names of things or of concepts. Does vox, the utterance, directly signify a thing in the world or does it instead signify the concept of the thing that exists in the mind of the person who speaks it?

William of Sherwood’s textbook:

The noun ought to be considered before the verb because it is a more important part than the verb, and so we must begin with it. And since every noun is an utterance and every utterance is a sound, we must begin with sound. Sound is the property to which the ears are sensitive; it is divided into vocal and nonvocal. Vocal sound is an utterance such as is made by an animal’s mouth. Nonvocal sound is footsteps, the crashing of trees, and the like. Utterances are divided into significative and non-significative. A significative utterance is one that signifies something; a non-significative one signifies nothing; for example, “buba blictrix.

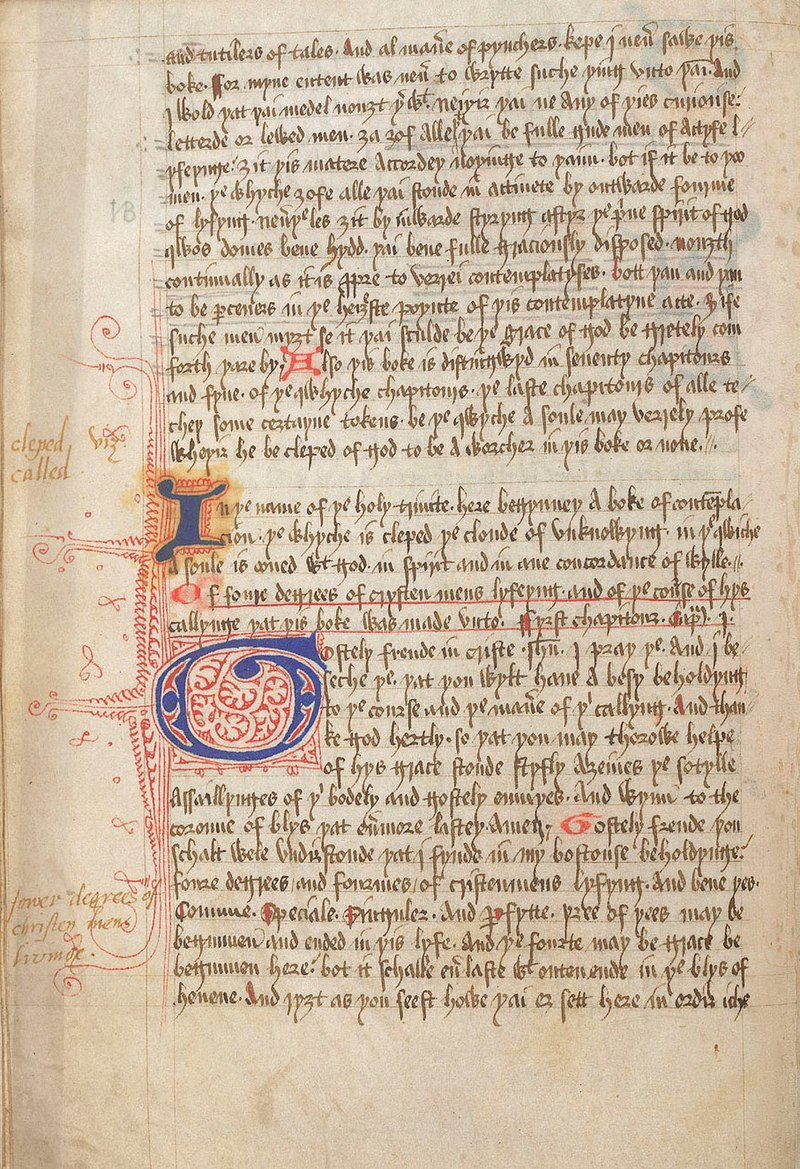

Cloud of Unknowing

Cloud of Unknowing is an anonymous work of Christian mysticism written in the later half of the 14th century.

The underlying message of the work suggests that to the way to know God is to abandon consideration of God’s activities and attributes, and surrender the ego to the realm of “unknowing” at which point one will be able to glimpse at the nature of God.

The book is for a student, but begins with this command

“do not willingly and deliberately read it, copy it, speak of it, or allow it to be read, copied, or spoken of, by anyone or to anyone, except by or to a person who, in your opinion, has undertaken truly and without reservation to be a perfect follower of Christ.”

It encourages seeking God not through intellect, but through love motivated contemplation, stripped of thought.

When we intend to pray for goodness, let all our thought and desire be contained in the one small word “God”. Nothing else and no other words are needed, for God is the epitome of all goodness.

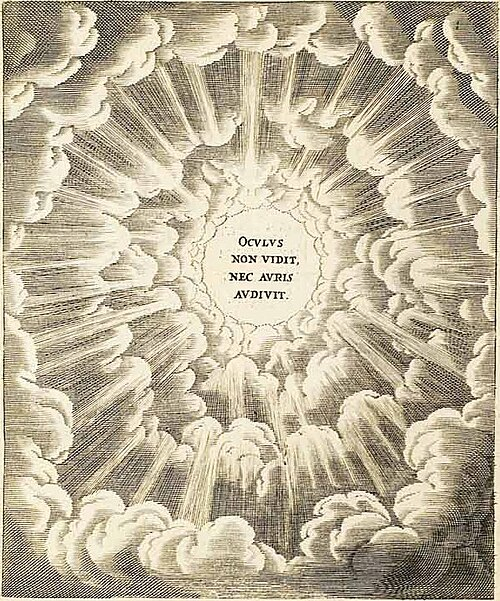

God is “what no eye has seen, nor ear heard.”

The work is called Apophatic theology a form of theological thinking which attempts to approach the divine via negation, speaking in terms of what may not be said.

Litil worde

Two examples of words are given in the text, God and Love but others may be used – but each one syllable. “To use a multisyllabic word is not to perform the work of unknowing in a less than ideal manner; it is not to perform it at all.”

In the Middle Ages the thought of the syllable was:

We can define the syllable as follows: the syllable is a writable utterance (vox literalis) that is emitted uninterruptedly under a single accentuation and a single breath.

The Cloud-author explains that if he insists on the use of the litil worde it is because such an utterance lends itself most fittingly to the purpose to which it will be put. This fitness inheres in a characteristic of this word that he calls its hoelnes: the way that it can be kept whole.

If someone asks:

If any thought presses upon you to ask you what you are seeking, answer him with no more words than this one word. And if he offers to explicate that word for you, using his impressive learning, and to tell you about its various aspects, tell him that you want to have it entirely whole, and not broken or undone.