created 2025-04-21, & modified, =this.modified

Why I’m reading

Following the tracks of Anathema! Medieval Scribes and the History of Book Curses by Marc Drogin through books related to manuscript writing.

Still curious about On Hands and in searching a notable quote from Survey of Text Etymology, Connections to Fiber, Body this work came up.

For the scribe, manual and mind-work are two hands whose fingers interlace.

When I was training to be an archivist, my mentor told me, “A thing is just a slow event.” - Isaac Fellman, Dead Collections

The Articulate Codex, Manuscription and Empathic Codicology

Period of study is 925-1080CE medieval Iberia. The Emirate and later Caliphate of Cordoba controlled the southern ⅔ of the peninsula, with the north divided among various Christian powers - Kingdom of Leon, county of castile, Pamplona and Catalonia.

Eighth-century Iberian theologian Beatus of Liébana:

The person who reads Scripture frequently (knows that) the letter is the body. But there is a spirit in the letter. This letter has a spirit, that is, a meaning. But no one can understand this meaning without the letter, that is, without the body.

English sentence is “I read a book” - the book is a passive recipient of the reader’s action. In ancient medieval practice, the activity went both ways:

We should read none save the best authors and such as are least likely to betray our trust in them, while our reading must be almost as thorough as if we were participating in the writing.

When Florentius imagines us reading in this codex, he understands the book as exactly this sort of gathering place. This is a place where reading is not an action performed upon a text, but rather an encounter in which both participants act upon each other and are changed as a result. The page might gain new marks upon its surface: pointing fin gers, pen-trials, doodles, sweat. And what St. Paul calls “the fleshly tables of the heart” (tabulis cordis car- nalibus) (2 Cor 3:3), inscribed by reading, become themselves living copies of the book.

The attentive reader will be more concerned with application of what is read into practice, rather than acquiring knowledge.

Ille - the book artist here, says he suffered to make this book he offers for our contemplation and use.

Florentius’s Body

The colophon felt like a message in a bottle.

For when we write, we attribute the agency of writing not to the pen by which the letters are traced, but to the hand of the writer.

Thought

I remember writing a text message to someone and considering the origin of it all, or at least just tracing a path.

It did not seem enough, to say that my hand generated the words. I could not fully place the words in me as well, me being the thinking thing writing this.

The feeling I got was that the words pass through me. Maybe I can position myself in way that reflects the sun, or catches the wind or the stream, like one of those undersea organisms who feel the current, filtering for other tiny organisms that it eats.

Or maybe it is like this, you hold something in your hand, like a immature dandelion, and let it go when you speak, the path interpreted by the world in possible ways.

I’m not saying my words are choiceless, or purely externally influenced. The feeling I just got was I couldn’t say that they started with me.

rel:The Routledge Handbook of SemanticsIt’s just that outside of me, the origins immediately become impossibly complex (not to say I have any sense of the inner complexity of words). Would I be able to trace a single word or concept, if that was all that there was?

It was just a feeling.

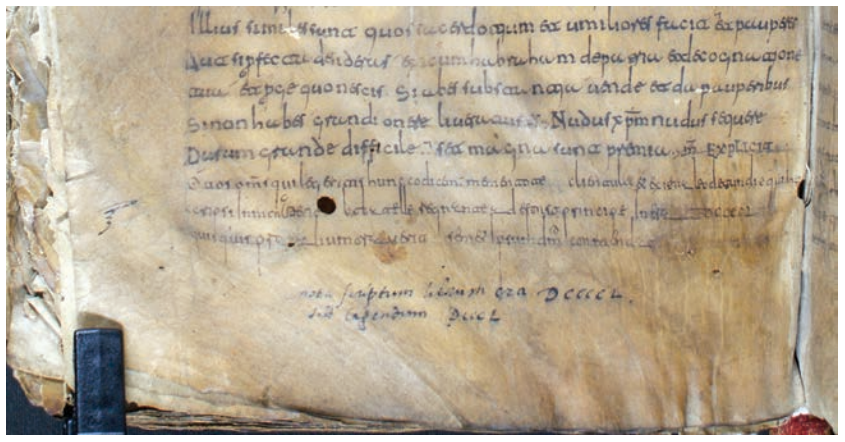

The Colophon:

I say that with the support of thundering celestial mercy this work is finished on the III of the ides of April, during the era nine times one hundred, twice ten, and four tens plus three. At the house set in a consecrated place and called Valeránica, in the honor, namely, of its patrons, saints Peter and Paul, great apostles and martyrs. I, Florentius, inscribed this book, at the command of the whole monastery represented in abbot Silvanus, when I had accomplished twice tenandtwo or nearly five and doubleten years of my little lifetime. These things certainly being done, I copiously pray and amply request that you who, in the future, might read in this codex direct your frequent prayer to the Lord for me, miserable Florentius, that we might deserve to please Lord Jesus Christ. Amen.

Use of second person:

Scribe and reader are joined, and joined now, in our respective times, by this artifact, the book. Any reader of the book is also a toucher of this book; our hands lie where his has been.

distich - a pair of lines; a couplet. rel:The Poem’s Heartbeat - A Manual of Prosody by Alfred Corn

Grammatica and Contemplative Manuscription

Oh all you who might read this codex in the future, remember me, poor servant Leodegundia, I who wrote this in the monastery of Bobatella in the reign of Prince Alfonsus in era dccc cl . One who prays for another commends the self to God.

Note

Leodegundia - Leodegundia was a Spanish noblewoman. Little is known about her, except that she was an accomplished writer and poet, and probably spent most her time at the royal court. Her work is identified with a popular group of painters, illuminators, and writers who flourished in Spain in the 10th century. Mozarabic in style, her work reflected that complex blend of Christian European and Eastern Arabic cultures, images, and traditions which came to define most Spanish art in the Middle Ages.

She imagines the gathering beneath her pen transformed by assembly with others like it into a codex— this one right here (hunc co- dicem, she writes), the one she wrote (hunc scripsi, she says) in 912 at Bobatella. She sees you sitting in front of this codex, at work in it as a reader as she is as a writer. She hopes that you are thinking of her.

In the book she made quick drawing of a maniculum in the outer margin, the extended index finger points to the colophon where the scribe reveals her name: the reader answers the call to think of her, in the book itself, with her own hand.

Monk zeal

we do not eat bread for nothing but in labor and exhaustion, working by night and day

who does not wish to work should not eat

Lectio Divina, in which reading morphed into meditation and meditation led back into reading.

Living with with text:

Each week all the 150 Psalms of David had to be recited at least once. Soon the novice would know them by heart… . Within a few weeks the child would associate the rustling of cloaks at the end of each prayer with the rising of the monks and the Gloria patri. The rhythmic repetition of the gesture of rising and bowing and its coincidence with a small canon of short formulas was easily associated with pious feelings and habits even before the novice was able to spell out the literal meaning of the Latin words. Deo gratias— thanks be to God—is felt as a response of relief at the end of a long Bible reading which takes place in the middle of the night. So also, in the refectory at noon time, it is the anxiously awaited sign that mealtime prayers are over and dinner may begin.

They discover by reading, they learn by meditating.

Ductus - has been defined by Mary Carruthers as “the way by which a work leads someone through itself: that quality in a work’s formal patterns which engages an audience and then sets a viewer or auditor or performer in motion within its structures, an experience more like traveling through stages along a route than like perceiving a whole object.

Thought

Calls to mind Ergodic Texts, which I have to read again.

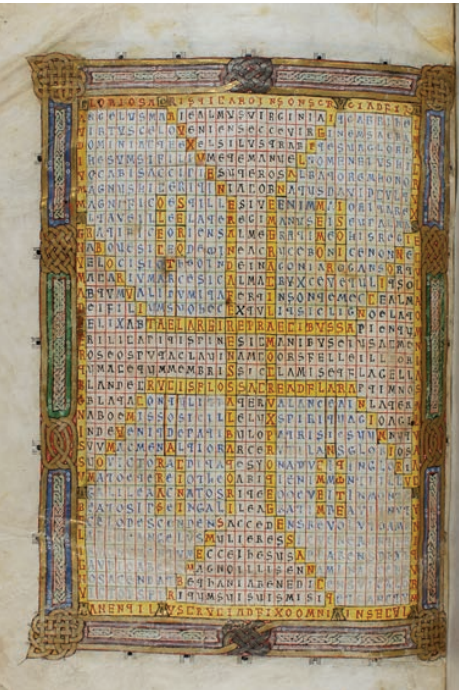

Florentius Labyrinth

rel: Wild Geese Returning - Chinese Reversible Poems by Michele Metail Oulipo

“FLORENTIUM INDIGNUM MEMORARE” is inscribed over and over,

“Remember Unworthy Florentius”

Thought

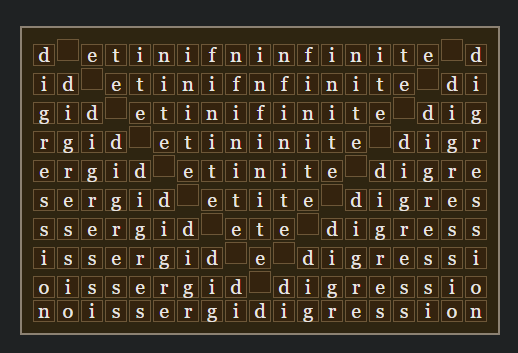

I find a builder, online, from the text where this is done in code. I put infinite digression in there.

Florentius cautions the readers to not use their fingers to trace. The prayer, in this grid of 260 letters repeats the phrase 354, 200 times.

No mortal unassisted by a counting machine could possibly arrive at this total. But what is likely is that a monastic user trained by lectio divina to think of reading less as pageturning forward movement than as a recursive, repetitive exploration would have come to feel that the labyrinth’s apparently infinite permutations made it an inexhaustible, nearmiraculous generator of prayer. Florentius’s shuttling prayer can lead the attentive user of this page into something very like meditatio

Vox

Every vox (voice/word) is either articulate or confused. If articulate, it can be captured in letters. Confused sounds cannot be written.

“The principal members of the human body are called artus and the smaller articuli. Anything that can be grasped by these writing articuli is itself an articular vox.”

Letters join the voice with page and hand; like the hand, they too can be understood as articulate bodies.

And sometimes also the very work done by someone’s hand is called their hand; as one is said to recognize a hand when they recognize what some-one has written. - Augustine, In Iohannis euangelium

Literalis vox - scriptible language, is called articulate because it is subject to joints, that is, fingers that write.

Servius explains in his commentary on Donatus, “What ever is read is vox articulata. If you unravel that which is joined together in reading, you produce discourse”

Writing extends one line and then goes back to spool out another; reading loosens, then reweaves, the net. This recursive flirtation with erasure is an essential characteristic of the grammarians’ understanding of lettered practice. It is etymologically (and thus, for the Isidorean Middle Ages, ontologically) built into letters themselves, according to Priscian and everyone who quotes him in the Middle Ages. The letter, they say, “is called littera either as a legitera (‘reading-road’), because it provides a path for reading, or derived from litura (erasure), as some prefer, because the ancients used to write mostly on wax tablets”

Isidore

The use of letters was invented for the sake of remembering things, which are bound by letters lest they slip away into oblivion.

also,

“When you receive a letter from your friend, dearest son, you would not hesitate to embrace it in place of your friend. When friends are separated, the second best consolation, if the beloved one is not present, is that his letters should be embraced in his stead”

The book as a nexus:quote

the book he made is not an object but a thing, a meeting place for human (and nonhuman) users as it moves through time.

Garden of Colophons

All over Castile and Leon, scribes were gathering “good and sweet-smelling fruits from the gardens on each other’s colophons.” Florentius’ grafts from other turns of phrase he learned from his teachers.

They address the future and present:

Dearest brothers, whosoever of you— present and future— might read this codex, may he read with a sharp mind, and may he understand well what he reads with the ears, eyes, and mouth of the heart.

Charter and Authority

Marks on a surface do not evoke presence strongly enough to stand up in court.

Identity in Idiosyncrasies

Modern autographs gain their authority from the fact that we now see them as “idiosyncratic signs of selves, intimately tied to the hand that produced them.”

In early Medieval law, validity springs from authority allograph - the names of the documents human agents.

“Medieval documentary truths,” writes Brigitte Bedos-Rezak, “are in a sense the truths of action done double, of action reproduced”

Makers and the Inscribed Environment

There is no need to seek a book: may the room itself be your book. Non opus est ut quaeratur codex: camera illa codex uester sit. - Augustine, Sermon 319

The inscriptions in monasteries,

What more shall I say to you? Shall I go on speaking? Read the four verses that we have written on the chapel wall: read, understand, and hold them in your heart. For that is why we wrote them there: so that all who choose to read might read, and read when they choose. So that all might understand, the verses are few; that all might read, they are publicly written. There is no need to seek a book: may the room itself be your book. – Augustine

May this room be your codex, said Augustine. The reverse is also true: may this codex be a room—an inscribed environment inhabited simultaneously by author, scribe, and reader.

Isidore of Seville:

The hand (manus) is so called because it is in the service (munus) of the whole body, for it serves food to the mouth and it operates every thing and manages it; with its help we receive and we give. With strained usage, manus also means either a craft or a craftsman.

Remember Maius: The Library and the Tomb

Alas! Woe to those who now refuse to examine the books, and to those who foolishly despise what will in the future be done in books. - Beatus of Liébana

The principal mode of representing a book goes from the open codex, to the boxed-closed book.

rel:Marginalia

“the book itself had been transformed from an instrument of writing and reading, to be used and thus open, into an object of adoration and a jewel- box of mysteries, not to be used directly and thus closed.”

The scribe’s tools are the reed-pen and the quill, for by these the words are fixed to the page. A reed-pen is from a tree; the quill is from a bird.

The Strange Time of Handwriting

Thought

This is the chapter I encountered in Survey of Text Etymology, Connections to Fiber, Body that made me pick up this book.

Time is not perceived on its own account, but by way of human activities.

Words throw a line into the future to be caught by readers.

This thing I write is subtracted from my life

Other portions of the body merely help the speaker, whereas the hands may almost be said to speak… . Do they not take the place of adverbs and pronouns when we point at places and things? - Quintilian

Every day we die, every day we are changed, yet still we think ourselves eternal. This very thing that I am dictating, that is written down, that I reread and correct, is subtracted from my life. As many punctuation marks as my secretary makes, so many are the forfeitures of my time. We write, we write back: the letters cross the seas, and as the keel of the ship cuts furrows in one wave after another, the moments of our lives slip away.

John Keats

This living hand, now warm and capable

Of earnest grasping, would, if it were cold

And in the icy silence of the tomb,

So haunt thy days and chill thy dreaming nights

That thou would wish thine own heart dry of blood

So in my veins red life might stream again,

And thou be conscience-calmed—see here it is—

I hold it towards you.

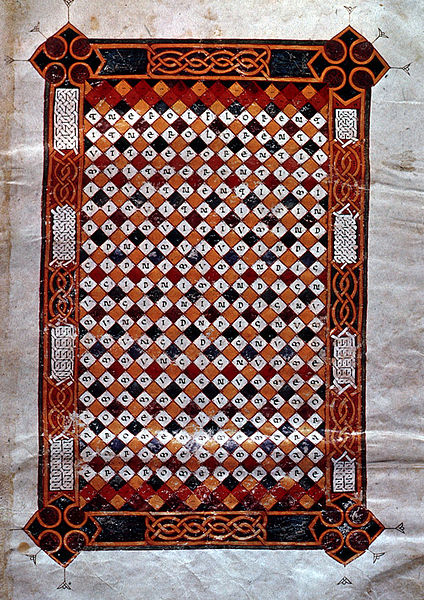

The Weavers of Albeda

Your eyes and fin gers habitually move left to right, but visual clues lead them down as well: letters in red drop vertically to make more words woven with common letters around the horizontal. These pattern- poems are Vigila’s practice distilled; they are what text is in its making: vertical warp, horizontal weft.

Fourth century poet Optatian thought of poems as verses woven in: verus intexti

Acrostic, the Literary Loom

“Any letter which is tinted in a descending verse is both contained in the one and runs crosswise with the other: it both stands upright, so to speak, as the warp, and runs crosswise as the weft—so far as may be on the page, a literary looming

Fortunatus Writes

I was repelled by the difficulty of this task, or— what was more difficult— hemmed in, both by the requirements of meter and the limitation on letters. What was I to do? How was I to advance? … Nor did the weaving permit me to roam, since the descending verses served as a bridle and a restraint. In fact, in this web it was not pos si ble to untie or loosen the strands by a single superfluous letter, lest a wandering thread exceed the mea sure and become tangled… . Accordingly, when I had gathered up all the strands of this web in measure and begun to weave them, the threads burst both themselves and me