created, $=dv.current().file.ctime & modified, =this.modified

tags: Photography

The basic meaning of photography is light writing. The medium received that designation in 1839 soon after photography was announced to the world. Despite changes in technology the photograph is still an image rooted in the agency of light. When a 19th century photographer placed a leaf on light-sensitive paper and exposed the paper to sunlight, the result was a photograph.

Thought

under-standing

rel:Neologistic Error Words Understand Etymology The text uses this form. I’m not sure I’ve seen it. Feels like understanding, but diminished (“under”). In a light search “under” in understanding is rooted in “amongst” and not “beneath.” Understanding meaning “to stand in the midst of.”But upon digging deeper, the search for a proper decomposition of the word and a logical path to what we have now, is futile. Language has evolved, through use. This is so poignant with the word we seek “understanding” and the face of a futile task.

In 1839 there were three times of photography

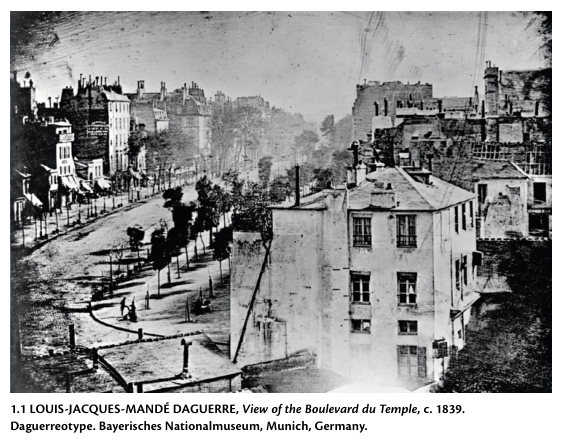

- Daguerrotype - an image produced on a silver-coated copper plate.

- Paper with camera

- Photogenic drawing - a contact print made by placing an object on light-sensitive paper. Paper based photographs had the ability to produce negatives from which additional copies could be produced.

Photography has always been cross-disciplinary

Origins

rel:Survey of Shadows

Indeed, the legend of the Corinthian Maid who preserved the look of her departing lover by tracing his cast-shadow outline on a wall points to the antiquity of the desire for lifelike replicas

The basic ingredients of photography—a light-tight box, lenses, and light- sensitive substances—had been known for hundreds of years before they were combined.

Indeed, all but the light-sensitive material was present in a technique for astronomical observation that used some European cathedrals like cameras. Beginning in the sixteenth century, the dark interiors of churches such as Santa Maria del Fiore in Florence, Italy, and Saint-Sulpice in Paris, France, were punctured with a small hole in the roof, which worked like a lens to focus an image of the sun on the floor below. There the sun’s movements were measured and used to establish the modern calendar.

Utopian Scifi origin (read this?): In utopian and speculative fiction written prior to 1800, only the 1760 novel Giphantie, by French writer Charles-François Tiphaigne de la Roche (1723–1774), anticipated something like the detailed transcription of the observable world that would occur with photography. In Giphantie, a narrator visits the hollow of the earth’s center, where a group of spirits creates highly illusionistic paintings. A canvas is smeared with a mysterious viscous material and placed before a desired scene. Like a mirror, it records every color and detail. After an hour’s drying time in a dark place, the picture becomes permanent. Arguably, Giphantie anticipated the use of light-sensitive chemicals, but the story did not involve a light- tight box or lenses—or a human operator.

SILHOUETTES, or shadow portraits, were part entertainment and part artistic venture. Silhouette-makers primarily served the bourgeoisie, but they also sold profile portraits on the streets and at parties. Some dextrously cut dark paper while observing a subject standing in profile; others used a candle to project the outline of a subject’s head on to a sheet of paper

physionotrace, party game.

NOTE

Camera Obscura, literally a “dark room.” Camera - 1708, “vaulted building; arched roof or ceiling,” from Latin camera “a vault, vaulted room” (source also of Italian camera, Spanish camara, French chambre), from Greek kamara “vaulted chamber, anything with an arched cover,” which is of uncertain origin.

Antonie Hercules Romuald Florence - Florence conceived photography after noticing that certain fabrics faded when exposed to light. In 1832, he began using the term photographie for his process, deriving it from the Greek words for light and writing.

Simultaneous invention makes it difficult to construct a linear chronology of photography and suggests, moreover, that there may have been other successful yet unknown attempts to invent photography.

Wedgwood and Davy’s experiments - sought to fix the image of an object’s shadow cast on paper or leather that had been made light sensitive by immersion in a silver nitrate solution, and they also attempted to capture images formed in a camera obscura. ” not permanent since the silver nitrate continued to react to light until the surface darkened”

Niépce - tried, without success, to use the negative as it is used today—that is, printing it to create a positive image, in which the tones are re-reversed and thereby corrected. Niépce put a similarly prepared plate in a camera obscura and exposed it in a window at his estate, Le Gras, near Chalon-sur-Saône. After about eight hours, he removed the plate, washed it with a mixture of oil of lavender and petroleum oil, and rinsed away those soluble areas of the plate where the bitumen of Judea had received less light. The resulting plate contained a poor but visible negative of the scene outside the window where the camera obscura had been placed.

Though not completely stable, Niépce’s View from the Window at Gras (c. 1826) is considered to be the world’s first permanent photograph

Daguerre’s photographic process was so simple that he, like Niépce before him, began to worry about someone stealing it, and robbing him of both his place in history and his long-sought financial reward.

Cyanotype - While it never became a major form of photography, the simplicity and low cost of the cyanotype made it a commercial success in the 1840s, and a favorite at the end of the nineteenth century for amateurs and scientists working in the field. Until the advent of digital image processing, it was widely used to produce blueprints for architects and builders.

The Second Invention of Photography

Photography described as “art-science.” The “art-science” label survived into the 1850s.

Poe opined that “all language must fall short of conveying any just idea of the truth … but the closest scrutiny of the photogenic drawing discloses only a more absolute truth, a more perfect identity of aspect with the thing represented.” He urged readers to imagine a “positively perfect mirror” that “is infinitely more accurate in its representation than any painting by human hands.”

Nature is only become handmaid to Art, not her mistress … Painters need not despair; their labours will be as much in request as ever, but in a higher field: the finer qualities of taste and invention will be called into action more powerfully: and the mechanical process will be only abridged and rendered more perfect.

Talbot and the Pencil of Nature - Talbot continued to development of photography after Daguerre stopped. He understood photography’s ability to present a sequence of images, the meaning of which proceeded not just from one example, but from all of them and from their arrangement.

Hippolyte Bayard tested limits of representation, teasing the sense that what the eye sees and the photograph records, might not be trustworthy.

Beginning in the early 1840s, several daguerreotype experiments reduced printed matter to a size so small that it had to be read with a microscope. This microform technique promised to condense rare books and manuscripts to an easily transportable and storable size.

In family Daguerreotypes: The photographic studio emerged as a new social space in which sitters could compose and record an image of how they desired to appear for acquaintances, strangers, and posterity.

The Expanding Domain - Popular Photography and the Aims of Art

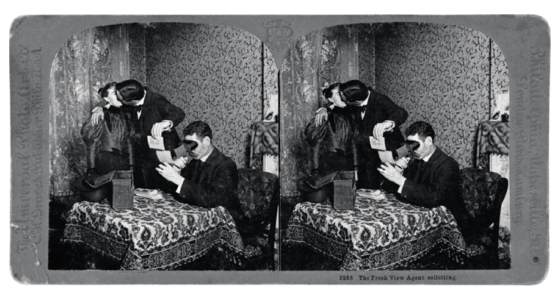

stereographic camera produced two simultaneous images, photographed as if one were seen with the left eye and the other with the right. Placed in a special viewer they gave the illusion of receding space.

the mind feels its way into the very depths of the picture

Form is henceforth divorced from matter. … Give us a few negatives of things worth seeing. … There is only one Coliseum or Pantheon; but how many millions of potential negatives have they shed—representatives of billions of pictures. … Every conceivable object of Nature and Art will soon scale off its surface for us. … The time will come when a man who wishes to see any object, natural or artificial will go to the Imperial, National, or City Stereographic Library and call for its skin or form. … We do now distinctly propose the creation of a comprehensive and systematic stereographic library, where all men can find the special forms they particularly desire to see as artists, or as scholars, or as mechanics, or in any other capacity.

CARTE-DE-VISITE - a small portrait photograph originally intended to be pasted onto the back of a visiting card. Up to eight images could be exposed on one photographic plate. There was a collecting urge. The vogue lasted 10 years, saturating the market with millions of images.

Photographs of art objects began.

Of photography as an art itself: The notion that photography could replicate art more accurately than other reproductive media arose because of the belief that photography itself was not an art—that is, not a medium open to imagination or subjective response. Rembrandt Peale - “We do not see with the eyes only, but with the soul.”

Charles Baudelaire saw photography supports as constricting human imagination. “Each day art further diminishes its self-respect by bowing down before external reality; each day the painter becomes more and more given to paint not what he dreams but what he sees.”

Darwin investigated the means by which photographs might be inexpensively included in the text. This had proved difficult because the presses that printed text ran too fast to reproduce photographs and type at the same time, and because most photographs needed to be printed on special paper, not newsprint. But a technique known as HELIOTYPE, invented by the photographer Ernest Edwards (1837–1903), who made a portrait of Darwin in 1868, used printing-press plates to reproduce photographs, and thus keep down the price of the book. The resulting images are not sharp and detailed, but they do convey facial gestures adequately.

Photographers continued to have difficulty creating clear images of the moon. Among the images in their 1874 publication The Moon, Considered as a Planet, a World, and a Satellite, were WOODBURYTYPE PRINTS of photographs of plaster models of the moon, constructed in accordance with Nasmyth’s drawings based on telescope observations

Modernity

1900s Kodak launched the Brownie camera, which was initially marketed towards children.

Though snapshots were mostly personal pictures, they did have a significant public impact. Snapshots not only reduced the number of professional portrait photographers; they also deepened the association between informality and photographic truth. Increasingly press photographs emulated the casual look of the snapshot, and the few artists remaining at newspapers made their drawings look more sketchy, as if done quickly on the spot.

rel:Postcards Picture postcards evolved after changes in nineteenth-century postal regulations in Europe and the United States authorized a simple, undecorated card with a message to be mailed. At the turn of the century, when printing methods such as the half-tone process facilitated reproduction of pictures and text, photographic postcards began to appear in large numbers.

At the height of the craze, Kodak manufactured the Folding Camera 3A, especially for producing picture postcards. The United States Post Office reported that from June 1907 to June 1908 more than 667 million postcards, many of them picture postcards, were sent.

Muybridge setup:

To make the photographs, Muybridge lined a raceway with 15- foot-wide sheeting, upon which lines were drawn at 21-inch intervals. As a horse rushed past, its hooves tripped cotton threads, which in turn tripped shutters on twelve cameras set up opposite the sheeting.

Muybridge setup:

To make the photographs, Muybridge lined a raceway with 15- foot-wide sheeting, upon which lines were drawn at 21-inch intervals. As a horse rushed past, its hooves tripped cotton threads, which in turn tripped shutters on twelve cameras set up opposite the sheeting.

X-Ray: The 1895 discovery of the X-ray by Wilhelm Conrad Röntgen (1845–1923), a Dutch-German physicist working in Germany, had profound effects outside science and medicine. Röntgen, who had a practical knowledge of photography, was experimenting with electricity and a cathode ray tube, which beamed an image on a screen, when he chanced to observe a force he would later call the “X” or unknown ray. It emanated from the cathode tube and caused a piece of cardboard coated with a fluorescent material to glow in the dark. He soon learned that the rays could pass through the human body, blackening a photographic plate except where they were absorbed by the calcium in bones (Fig. 7.19). His X-ray photographs looked like shadowgraphs, such as those made by William Henry Fox Talbot and others decades earlier (see here). The public defined the X-ray as a kind of photography, even though it was not created by light waves.

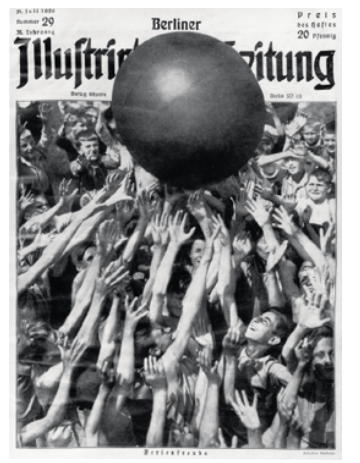

Art and the Age of Mass Media

It is not hard to understand how the DADA movement in Europe drew on artists’ reactions to the killing fields of World War I

Photojournalism:

Newspaper and magazine images, by contrast, were selected by photoeditors or advertising designers, circulated for a short time, then superseded by more images. The glut of images was producing an increasingly visually sophisticated audience that rapidly came to see printed images as transitory and expendable.

Newspaper and magazine images, by contrast, were selected by photoeditors or advertising designers, circulated for a short time, then superseded by more images. The glut of images was producing an increasingly visually sophisticated audience that rapidly came to see printed images as transitory and expendable.

rel:Expression

El Lissitzky - He renounced self-expression in art, along with easel painting, which he associated with a corrupt past and stagnant aesthetics. With others, Lissitzky insisted that the artists role was now linked to industry and to reshaping everyday life. In avant-garde circles, the terms “production art” and “production artist” began being used, to indicate that the artist would employ technology in order to mold a new society. Photography was favored precisely because it was the product of a machine that could be mass produced by other machines.

Rodchenko wholeheartedly accepted photography because he felt it freed artists from inherited aesthetic ideas, especially perspective and the other techniques used to render the world as it is, rather than as it might be. He promoted the notion that new concepts could not be expressed in old media, and was a leading proponent of faktura, the idea prominent in Soviet art theory that an artist should discover a mediums distinctive capabilities by experimenting with its inherent qualities.

rel:Dada - Art and Anti-Art

During World War I, a group of writers, artists, and poets met at the Cabaret Voltaire in Zurich, Switzerland, a cultural outpost in a politically neutral country. The group strongly objected to the war and to the bankrupt materialism of the age. They envisioned a new art that expressed their despair, but that would also sweep away tiresome conventions and intellectual barriers. The Romanian-born artist Tristan Tzara (1896–1963), who wrote the Dada Manifesto of 1918, saw the task to be done as “a great negative work of destruction.”

The origins of the name “Dada” seem to owe to a moment when two enthusiasts thrust a paper knife into a French- German dictionary, and it pointed to the word “dada,” or hobby horse.

Hannah Höch amd Hasumann were two early Dadaists who make photomontage. Hausmann explained that he added machinery, including an automobile steering wheel, to the main figures head because he was interested in portraying a man who had machines for brains.

In Paris, Dadaists turned away from the Berlin group’s political activism in order to take up a wider cultural criticism.

“Automatic writing,” Breton wrote, “is a true photography of thought.”

Breton rejected the anarchism of Dada, which relied on an ability (difficult to sustain indefinitely) to shock, disturb, or outrage viewers. He sought a more constructive program that would still be based on the power of the unconscious and irrational mind. This led to the founding of the Surrealist movement.

Man Ray and Dada NY.

The first and only issue of the magazine New York Dada appeared in 1921 with a photograph of Duchamp disguised as his female alter ego Rrose Sélavy, which had been affixed to a recycled perfume bottle

rel:Surrealism

Rather than emphasizing social change on the state level, the Surrealists advocated the transformation of human perception and experience through greater contact with the inner world of imagination.

Hans Bellmer encountered Berlin Dadaists while studying engineering. After a number of eerie personal incidents, including attending a performance of Jacques Offenbach’s (1819–1880) opera The Tales of Hoffmann, about a beloved automated doll that is demolished, he was inspired to create his own dolls and photograph them.

SOLARIZATION involves briefly exposing a print or negative to light during the development process. The result is a reversal of tones, especially along the edges of objects. Sometimes called edge reversal, solarization is unpredictable, which made it a favorite technique of the Surrealists. Ubac also developed a technique called brûlage, or burning, in which film emulsion was melted to produce swirling shapes.

Post Modern

The Postmodern notion of indeterminate, circular meaning gave the blurred image a new lease on life as a multivalent symbol, alluding to transient and fragmentary moments, fuzzy or disfigured identities, or indistinct and ambiguous knowledge. Interestingly, blur has had many uses in the history of photography, the best-known of which was the Pictorialist image, with its pretensions to High Art. More recently, photographers such as Duane Michals blurred the actions of human figures to add mystery and wonder to a scene.

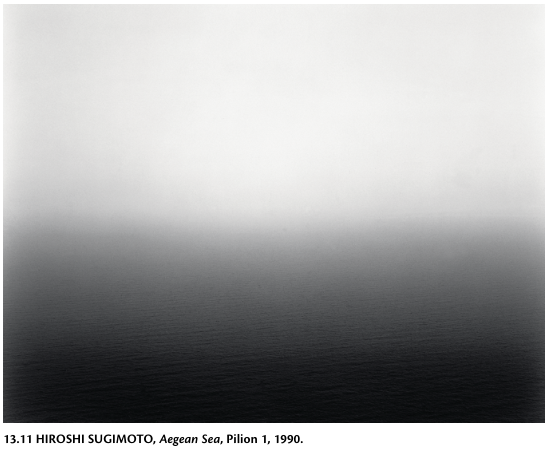

Hiroshi Sugimoto -

For more than two decades, he has traveled the world seeking high vantage points from which to aim his camera at the point where the sky and ocean come together at the horizon