created, $=dv.current().file.ctime & modified, =this.modified

tags: Language Linguistics

related: Written text and spoken text

Thought

I think what this is related to is Written text and spoken text, which I was independently thinking of? And discovered this book, which is a funny way of circling back.

I find myself entrenched in a world and a mindset that is text-based (even though I devalue it at times, it cannot be avoided — such as this living document.) So this is valuable for me, to situate myself in this ancient world where the written word was just emerging and arose so close with constant orality. (also, I feel it isn’t an easy or clear divide - the development of the oral and written obviously continues, even in my own life where I see first-hand toddlers with no ability to read learning words).

NOTE

Walter J. Ong’s classic work provides a fascinating insight into the social effects of oral, written, printed and electronic technologies, and their impact on philosophical, theological, scientific and literary thought.

Orality is thought and verbal expression in societies where the technologies of literacy (especially writing and print) are unfamiliar to most of the population.

Despite the striking success and subsequent power of written language, the vast majority of languages are never written, and the basic orality of language is permanent.

Broad history

- Ancient medieval rhetoric

- because it was rhetoric - an oral art - that ultimately took all knowledge as its province

- The European Reformation

- where print based Ramism reformed knowledge as well as religion; a move that linked religion with the rise of capitalism and created a path-dependency for Methodism and scientific method alike

- Enlightenment

- Both scientific and Scottish

- American Republic

- Technological determinations of modern knowledge

- where, writing and print literacy have transformed human consciousness as a whole, while a “secondary orality” has emerged with digital media.

- where, writing and print literacy have transformed human consciousness as a whole, while a “secondary orality” has emerged with digital media.

Many of the features we have taken for granted in thought and expression in literature, philosophy and science, and even in oral discourse among literates, are not directly native to human existence as such but have come into being because of the resources which the technology of writing makes available to human consciousness.

Homo Sapiens have existed between 30K and 50K years. The earliest scripts date from 6K years ago.

The Orality of Language

Some non-oral communication is exceedingly rich – gesture, for example. Yet in a deep sense language, articulated sound, is paramount. Not only communication, but thought itself relates in an altogether special way to sound. We have all heard it said that one picture is worth a thousand words. Yet, if this statement is true, why does it have to be a saying? Because a picture is worth a thousand words only under special conditions – which commonly include a context of words in which the picture is set.

Indeed, language is so overwhelmingly oral that of all the many thousands of languages – possibly tens of thousands – spoken in the course of human history only around 106 have ever been committed to writing to a degree sufficient to have produced literature, and most have never been written at all.

Of the 3K languages spoken that exist today, only some 78 have literature*

Research

According to Ethnologue, there are currently 7,164 living languages. The countries with the most languages are Papua New Guinea (840), Indonesia (709), Nigeria (517), India (453) and the USA (335)

According to Wikipedia, at least 3,866 languages “make use of an established writing system”. This includes writing sytems for extinct languages and constructed languages, shorthand systems, Braille and other notations systems, and many writing systems listed that are rarely, if ever, used.

Grapholect - is a transdialectical language formed by deep commitment to writing. “A written variant of a language, analogous to a spoken dialect of a language.”

Standard English has accessible for use a recorded vocabulary of at least a million and a half words, of which not only the present meanings but also hundreds of thousands of past meanings are known.

‘Reading’ a text means converting it to sound, aloud or in the imagination, syllable-by-syllable in slow reading or sketchily in the rapid reading common to high-technology cultures. Writing can never dispense with orality.

Thought

On the equal viability of reading audio books and physical books?

Thought

Orality keeps coming up. My understanding of it is an infant thing. But it makes me wonder, if I could read a book about a subject, or about an esoteric term, where the term is constantly referenced and circled back to, and still not understand the word? Like if I could build up this understanding through context, purely in the book.

I guess this could happen, in a way, if I were to just swap out a word with an imaginary word that has the same meaning of the word. So write a book about Holigtress, which I’m just using to mean “All green tree frogs.” It’s a poor example, but I think the dawning of what is being spoken, like a puzzle, would be fun to unfurl in context.

In Ancient Greece: After the speech was delivered, nothing of it remained to work over. What you used for ‘study’ had to be the text of speeches that had been written down – commonly after delivery and often long after (in antiquity it was not common practice for any but disgracefully incompetent orators to speak from a text prepared verbatim in advance In this way, even orally composed speeches were studied not as speeches but as written texts.

Written words are residue.

When an often-told oral story is not actually being told, all that exists of it is the potential in certain human beings to tell it. Oral tradition has no such residue to deposit.

Though words are grounded in oral speech, writing tyrannically locks them into a visual field forever.

rel: Ada Lovelace Letters Quipu

‘Text’, from a root meaning ‘to weave’, is, in absolute terms, more compatible etymologically with oral utterance than is ‘literature’, which refers to letters etymologically/(literae) of the alphabet.

rhapsodize - means in Greek “to stitch songs together”

To dissociate words from writing is psychologically threatening, for literates’ sense of control over language is closely tied to the visual transformations of language: without dictionaries, written grammar rules, punctuation, and all the rest of the apparatus that makes words into something you can ‘look’ up, how can literates live?

Fortunately, literacy, though it consumes its own oral antecedents and, unless it is carefully monitored, even destroys their memory, is also infinitely adaptable. It can restore their memory, too. Literacy can be used to reconstruct for ourselves the pristine human consciousness which was not literate at all – at least to reconstruct this consciousness pretty well, though not perfectly (we can never forget enough of our familiar present to reconstitute in our minds any past in its full integrity). Such reconstruction can bring a better understanding of what literacy itself has meant in shaping man’s consciousness toward and in high-technology cultures. Such understanding of both orality and literacy is what this book, which is of necessity a literate work and not an oral performance, attempts in some degree to achieve.

The Modern Discovery of Primary Oral Cultures

Earlier linguists had resisted the idea of the distinctiveness of spoken and written languages. Despite his new insights into orality, or perhaps because of them, Saussure takes the view that writing simply represents spoken language in visible form.

Homer: Parry’s discovery might be put this way: virtually every distinctive feature of Homeric poetry is due to the economy enforced on it by oral methods of composition. These can be reconstructed by careful study of the verse itself, once one puts aside the assumptions about expression and thought processes engrained in the psyche by generations of literate culture.

Early written poetry everywhere, it seems, is at first necessarily a mimicking in script of oral performance. The mind has initially no properly chirographic resources. You scratch out on a surface words you imagine yourself saying aloud in some realizable oral setting. Only very gradually does writing become composition in writing, a kind of discourse – poetic or otherwise – that is put together without a feeling that the one writing is actually speaking aloud (as early writers may well have done in composing).

Psychodynamics of Orality

rel: Magic Action Words

Sounded word as power and action. It is possible to generalize about the psychodynamics of primarily oral cultures (cultures untouched by writing).

Try to imagine a culture where no one has ever ‘looked up’ anything.

Sound only exists when it is going out of existence. It is not simply perishable but essential evanescent. When I pronounce the word permanence, by the time I get to the -nence the perma- is gone and has to be gone.

It isn’t surprising that oral peoples commonly and probably universally consider words to have great power. Words come rom inside a living organism.

Names convey power: Names do give human beings power over what they name: without learning a vast store of names, one is simply powerless to understand, for example, chemistry and to practice chemical engineering. And so with all other intellectual knowledge. Secondly, chirographic and typographic folk tend to think of names as labels, written or printed tags imaginatively affixed to an object named. Oral folk have no sense of a name as a tag, for they have no idea of a name as something that can be seen. Written or printed representations of words can be labels; real, spoken words cannot be.

How do oral cultures recall without lookup? Your thought must come into being in heavily rhythmic, balanced patterns, in repetitions or antitheses, in alliterations and assonances, in epithetic and other formulary expressions, in standard thematic settings.

Thought

Syntax is order. Despite de-emphasis of “formulary expressions” speech and written word has structure which allow a common ground. These vestigial patterns are now treated as literary.

After reading onward, the text continues to describe this as “overwhelmingly massive oral residue”

If I had waited I’d see this is where the text goes. Continuing…

Of course, all expression and all thought is to a degree formulaic in the sense that every word and every concept conveyed in a word is a kind of formula, a fixed way of processing the data of experience, determining the way experience and reflection are intellectually organized, and acting as a mnemonic device of sorts. Putting experience into any words (which means transforming it at least a little bit – not the same as falsifying it) can implement its recall. The formulas characterizing orality are more elaborate, however, than are individual words, though some may be relatively simple: the Beowulf-poet’s ‘whale-road’ is a formula (metaphorical) for the sea in a sense in which the term sea’ is not.

Awareness of the mnemonic base of the thought and expression in primary oral cultures…

Indeed, most words in the Iliad and the Odyssey occur as parts of identifiable formulas.

Palindromic Poem

Thoughts

This goes back to my thought about how to compose a palindromic poem. Since a palindrome has mirrored halves, there’s a tension between intentional choice, and acceptance in its writing. It is as if half of the poem is written, which simultaneously forces language decisions, so the other half (that is mirrored) is more of an accepted consequence of the former.

This tension exists elsewhere in writing, but the overt structural rules make it really apparent in palindrome.

Many poets will do this to adhere to form, selecting from a set of rhyming words rather than “conjuring” one. Maybe this is similar to use of a reference in drawing, which by some outside of the art world would see as “cheating” but is a valid and often used technique. What is created need not always be conjured completely from within, produced only by the artist, if such a thing is even possible.

Music and Oral Memory

Music may act as a constraint to fix a verbatim oral narrative.

Oral memory differs from textual memory in that oral memory has a high somatic composition. Traditional composition has been associated with hand activity. Aborigines of Australia and other areas often make string figures together with their songs. Other people manipulate beads on strings. Bards included strings or drums. They’d often rock backward and forward the torso. rel: Quipu

Words are not signs - Derrida made a point that ‘there’s no linguistic sign before writing But neither is there a linguistic sign after writing, if the oral reference of the written text is adverted to. Thought is nested in speech, no in texts, all of which have their meanings through reference of the visible symbol to the world of sound. What the reader is seeing on this page are not real words but coded symbols whereby a properly informed human being can evoke in his or her consciousness real words, in actual or imagined sound. It is impossible for script to be more than marks on a surface unless it is used by a conscious human being as a cue to sounded words, real or imagined, directly or indirectly.

NOTE

It is impossible for script to be more than marks on a surface unless it is used by a conscious human being as a cue to sounded words, real or imagined, directly or indirectly.

Thinking on this. I have a visual of this vast library (as I often do) where millions of books lie dormant. The text on their pages, all potential inner sound. Over years and years the pages crystalize. The great library becomes a dim cavern. rel:Library Scholars

Writing Restructures Consciousness

Writing establishes what has been called “context-free” language or “autonomous discourse”, which cannot be directly or contested as oral speech can be because discourse has been detached from its author.

Oral cultures know a kind of autonomous discourse in fixed ritual formulas, as well as vatic saying or prophesies for which the utterer himself or herself is considered only a channel, not the source. The Delphic oracle was not responsible for her oracular utterances, for they were held to be the voice of the god. Writing, even more in print has this vatic quality.

Vatic - describing or predicting what will happen in the future.

There is no way to directly refute a text. After total and devastating refutation, it says exactly the same thing as before. This is one reason why “the book says” is popularly tantamount to “it is true.” It is also one reason by books have been burnt. rel:Transmutation and Transformation.

A text stating what the whole world knows is false will state falsehood forever, so long as the text exists. Text are inherently contumacious. “(especially of a defendant’s behavior) stubbornly or willfully disobedient to authority.”

rel:Written text and spoken text

Most persons are surprised, and many distressed, to learn that essential the same objection commonly urged today against computers were urged by Plato in the Phaedrus and in the Seventh Letter against writing. Writing, as Plato has Socrates say, is inhuman, pretending to establish outside the mind what in reality can only be in the mind. It is a thing, a manufactured product.

Secondly, he argues writing destroys memory. Those writing become forgetful, relying on an external resource for what they lack in internal resources. Writing weakens the mind.

Third, written text is unresponsive. If you ask a person to explain their statement, they might. If you ask a text you get nothing but the same words.

Also, written word cannot defend itself as the natural spoken word can: real speech and thought always exist essentially in a context of give-and-take between real persons.

1477 Hieronimo Squarciafico - who promoted printing of Latin classics, also argued the abundance of books makes men less studious.

Others saw it as a welcome leveler, everyone becomes a wise man or woman.

rel:Camera Lucida, Reflections on Photography - Barthes La mort de l’autheur - Barthes

Paradox of writing: its close association with death. Plato charged that writing is inhuman, thing-like and destroys memory. The paradox lies in the fact that the deadness of the text, its removal from the human lifeworld, its rigid visual fixity, assures its endurance and its potential for being resurrected into limitless living contexts by a potential infinite number of living readers.

Plato was thinking of writing as an external, alien technology, as many people today think of a computer. In contrast to oral speech, writing is completely artificial (said not in condemnation but praise.)

To live and understand fully, we need not only proximity but also distance.

What is writing or Script?

Writing was a very late development in human history. The first script was developed amongst the Sumerians in Mesopotamia around the year 3500 BC. Human beings had been drawing pictures for countless millennia before this.

Scripts have complex antecedents. Most if not all scripts trace back directly or indirectly to some sort of picture writing, or, sometimes perhaps, at an even more elemental level, to the use of tokens.

Thought

In Love knot language the mention of living a life of communication with your love in a private knot language. It seems that this is just an earlier stage of what we already have in written texts. It is just a return, as the text I am writing now has roots in a different form of encoding transactions with tokens such as literal clay tokens, or even quipu.

Out of pictographs (a picture of a tree represents the word for a tree) scripts develop other kinds of symbols.

- ideograph where meaning is a concept not directly represented by the picture, but established by code: the chinese pictograph the stylized picture of two trees doesn’t represent two trees but woods

- the rebush - a type of phonogram (sound-symbol) - pictures of a mill, a walk and a key, could represent milwaukee.

All pictographic systems require a dismaying number of symbols. One advantage of a pictographic system is that even with different dialects (mutually incomprehensible), readers are able to understand each other’s writing.

The most remarkable fact about the alphabet is that it was invented only once. It was worked up by a Semitic people in 1500BC in the same geographic area where the first of all scripts , the cuneiform, but two millennia later. All alphabets develop from the original Semitic development, though the design of the letters may not always related to the Semitic design.

Korea AD 1443 King Sejong decreed alphabet should be devised for Korean. Up to that point Korean had been written only with Chinese characters, laboriously adapted to fit the vocab of the Korean. Koreans had laboriously mastered this Sino-Korean chirography and were reluctant to make their skills obsolete. An alphabet was made to accommodate Korean phonemics and aesthetically designed to produce an alphabetic script with something of the appearance of Chinese characters. But serious writers continued to use Chinese with this new script used for vulgarian, practical and unscholarly purposes. Only in the 20th century would it achieve its present (still less than total) ascendency. \

The Onset of Literacy

Writing is often regarded at first as an instrument of secret and magic power. Traces of this early attitude can be found etymologically: the Middle English “grammarye” or grammar, referring to book-learning, came to mean occult or magical lore, and through one Scottish dialectical form has emerged in our present english as ‘glamor’ (spell-casting power). The futhark or runic alphabet has been associated with magic. Scraps of writing are used as magic amulets, but they can also be valued simply because of the wonderful permanence they confer on words. An Ibo villager hoarded his house with every bit of printed material that came his way - newspaper, cartons, receipts, since it all seemed too remarkable to throw away.

In early literacy culture a “craft-literacy” can occur, where writing is a trade practiced by craftsmen, and people hire people to write letters for them in the manner you would hire a stone-mason to build a house.

Written documents were often authenticated not in writing but by symbolic objects (such as a knife attached to a document by a parchment thong). Symbolic objects alone could serve as instruments for transferring property. (Conveying an estate by offering a sword on an altar.)

In high technology cultures today, each person lives each day in a frame of abstract computed time enforced by millions of printed calendars, clocks and watches. In 12th century England there were none of these. Most persons did not know and never even tried to discover in what calendar year they had been born.

Lists and body parts of text

Visual presentation of verbalized material in space has its own particular economy, its own laws of motion and structure. Texts in various scripts around the world are read variously from left to right, right to left, top to bottom. But never, so far as known, from bottom to top.

NOTE

Boustrophedon: (in a manner of, like an ox turns, while plowing)

Stoichedon: the practice of engraving ancient Greek inscriptions in capitals in such a way that the letters were aligned vertically as well as horizontally. Texts of this form give the appearance of being composed in a grid with the same number of letters in each line and each space in the grid filled with a single letter; hence, there are no spaces between words, and no spaces or punctuation between sentences.

This style of inscription affords reconstruction of fragmentary text. With formulaic construction and knowledge of the precise number of missing letters it is possible to make an informed guess.

“Head”ings: chapter derives from the Latin caput meaning head (as of the human body. Pages have heads and feet for footnotes.

Oral culture has no concept of headings etc.

Some Dynamics of Textuality

The condition of words in a text is quite different from their condition in spoken discourse.

The writer must fictionalize the reader. The reader must also fictionalize the writer. When my friend reads my letter, I may be in an entirely different frame of mind from when I wrote it.

Writing allows for deep introspection.

Writing and print develop special kinds of dialects. Most languages have never been committed to writing at all.

NOTE

Grapholect - a written variant of a language, analogous to a spoken dialect of a language.

The grapholect bears the marks of the millions of minds which have used it to share their consciousnesses with one another. Into it has been hammered a massive vocabulary of an order of magnitude impossible for an oral tongue. The Webster Dictionary prefaces have stated that they could have included “many times” more than the 450K words it includes.

Rhetoric gradually migrated from the oral to the chirographic world. Classical skills in it were put to use in writing. Traditional parts of rhetoric (invention, arrangement, style, memory and delivery) - with memory not applicable to writing and minimization of delivery.

Print, Space and Closure

Hearing Dominance Yields to Sight Dominance

Print is distinct from writing and oral culture.

Print made the Italian Renaissance a permanent European Renaissance and implemented the Protestant Reformation and reoriented Catholic religious practice, affected modern capitalism, made possible the rise of modern sciences, and otherwise altered social and intellectual life.

Chirographic control of space tends to be ornamental, ornate, as in calligraphy. Typographic control typically impresses more by its tidiness and inevitability.

Space and Meaning

Writing had reconstituted the originally oral, spoken word in visual space. Printed embedded the word more definitively. This can be seen in developments such as lists, especially alphabetic indexes, in the use of words (instead of iconographic signs) for labels, in the use of printed drawings of all sorts to convey information, and in the use of abstract geometric space to interact geometrically with printed words in a line of development that runs from Ramism to concrete poetry and Derrida’s logomachy with printed text.

Thought

When interviewing I recall hearing a question regarding what is the purpose of an array? What is an array? When would one use an array over an object?

Besides the obvious train of thought this was enjoyable to think about. What do we get from this ubiquitous method of assembling in order, like a list?

So this has me thinking “What is an array?” (I was thinking here more mentally what an array represents and what ordered representation affords.

Indexes

rel:Manicule, Body in Books and Analysis of Love

Lists begin with writing.

Ugaritic script in 1300BC was an example of early lists in scripts. Information in the lists is abstracted from the social situation it had been embedded and also from the linguistic context (in oral utterances normally nouns are not free-floating in lists, but are embedded in the sentences; rarely do we hear an oral recitation of a string of nouns unless they are being read off a written list.) In this sense lists have no oral equivalents.

Early list delimiters: the word dividers to separate items from numbers, ruled lines, wedged lines, and elongated lines.

Egyptian Onomasticon is mentioned.

Materials are more immediately retrievable through spatial organization.

Alphabetic indexes show strikingly the the disengagement of words from discourse and their embedding in typographic space. Two manuscripts of a given work, even if copied from the same dictation, almost never correspond page for page, each manuscript of a given work would normally require a separate index. rel:Repeat a day (some natural resistance to identical repetition)

Paragraph was a favorite sign, ¶, not a unit of discourse at all. Parts of Language, Transcription Structure, Sentences

Indexes seem to have been valued at times for their beauty and mystery rather than their utility. In 1286, a Genoese compiler could marvel at the alphabetical catalogue he had devised as due not to his own prowess but ‘the grace of God working in me’

Index is a shortened form of the original index locorum or index locorum communium - index of places, or index of common-places. The loci had originally been vaguely thought of as ‘places’ in the mind where ideas were stored. In the printed book, these vague psychic places between quite physically and visibly localized. The new noetic world was shaping up, spatially organized.

In this new world the book was less like an utterance, and more like a thing. Books of this era lacked title pages, and often titles - so a book from pre-print manuscript culture is catalogued by its incipit (latin for it begins) or the first words of its text.

Thing-a-fying

Often in medieval western manuscripts instead of a title page, the text proper might introduce by way of an observation to the reader, just as a conversation might start with a remark from one person to another (“here you have, dear reader, a book which so-and-so wrote about…“)

Homer would hardly have begun a recitation of episodes from the Iliad by announcing ‘The Iliad’.

Content/Contents:

Once print has been fairly well interiorized, a book was sensed a kind of object that ‘contained’ information, rather than as earlier a recorded utterance.

Each individual book in a printed edition was identical, where manuscripts were not even when presenting the same text. Books were duplicates of one another. Early on the iconographic drive was still strong, with emblematic engraved title pages filled with allegorical figures and nonverbal designs.

NOTE

With words, and the need for duplication/identity to be valid.

Meaningful surface - hand drawn technical drawings soon deteriorated in manuscripts because even skilled artists miss the point of an illustration they are copying unless they are supervised by an expert in the field the illustrations belong to. Otherwise a sprig of white clover copied by a succession of artists can end up looking like an asparagus rel:Transmutation and Transformation

NOTE

Telephone, telestrations and generation loss. When you draw something and the identity isn’t clear, parts become replaced completed by the interpreter.

Exact observation does not begin with modern science. For ages, it has always been essential for survival among, for example, hunters and craftsman of many sorts. What is distinctive of modern science is the conjecture of exact observation and exact verbalization: exactly worded descriptions of carefully observed complex objects and processes. The availability of carefully made technical prints, such a woodcuts and engravings implemented such exactly worded descriptions.

Eisenstein (1979, p. 64) suggests how difficult it is today to imagine earlier cultures where relatively few persons had ever seen a physically accurate picture of anything.

Thought

This was precisely the thought I was having earlier with explaining a xylophone to the degree it could be identically reproduced, and how to isolated the idea of a xylophone to a minimal set of words and information necessary to do this.

Typographic space -

Because visual surface had become charged with imposed meaning and because print controlled not only what words were put down to form a text but also the exact situation of the words on the page and their spatial relationship to one another, the space itself on a printed sheet - “white space” as it is called - took on high significance that leads directly into the modern and post-modern world.

Spatial relationships will not survive the vagaries of successive copiers.

In Tristram Shandy (1760–7), Laurence Sterne uses typographic space with calculated whimsy, including in his book blank pages, to indicate his unwillingness to treat a subject and to invite the reader to fill in.

Space here is equivalent to silence.

rel:A radium of the Word

Print removed the ancient art of orally based rhetoric from the center of academic education. It made possible on a large scale the quantification of knowledge, through the use of diagrams and charts. Print produced dictionaries which fostered the correctness of language.

Print was a major factor in the development of a sense of personal privacy. It produced books smaller and more portable than those common in manuscript culture, setting the stage for solo reading in a quiet corner or eventually completely silent reading.

Intertextuality refers to a literary and psychological commonplace: a text cannot be created simply out of lived experience. A novelist writes a novel because he or she is familiar with this kind of textual organization of experience.

Post-typography: electronics

Despite what is sometimes said, electronic devices are not eliminating printed books but are actually producing more of them. Electronically taped interviews produce ‘talked’ books and articles by the thousands which would never have seen print before taping was possible.

Electronic tech has brought us into an age of secondary orality. This new orality has striking resemblances to the old in its participatory mystique, its fostering of the a communal sense, its concentration on the present moment, and even its use of formula. (Telephone, radio, television and various kinds of sound tape)

Oral Memory, The Story Line and Characterization

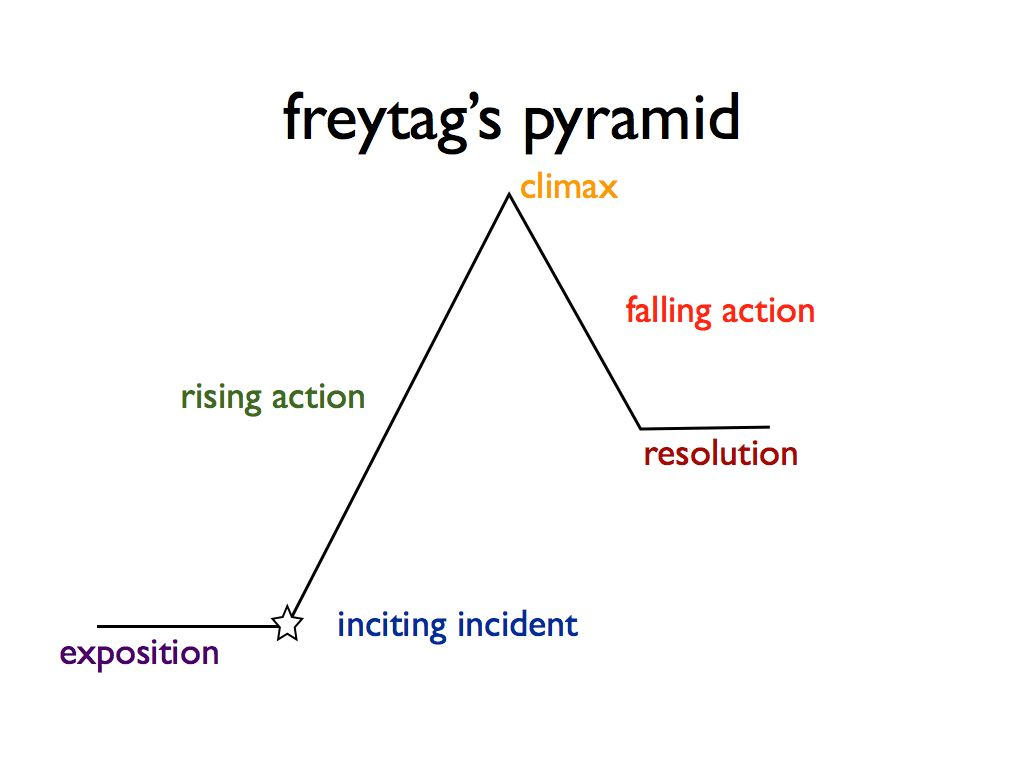

Persons from literate typographic cultures (now) are likely to think of consciously contrived narrative as typically designed in a climactic linear plot often diagrammed as ‘Freytag’s Pyramid’

Ancient Greek oral narrative was not plotted this way. Horace writes that the epic poet “hastens into the action and precipitates the hearer into the middle of things” - the poet will disregard the temporal sequence, report a situation and then only much later get into detail of how it came to be.

Why was all lengthy narrative before early 1800s more or less episodic, all over the world? We see the first detective story in 1841 with EAP’s The Murders in the Rue Morgue.

Peabody brings out a certain incompatibility between linear plot (Freytag’s pyramid) and oral memory, as earlier works were unable to do. He makes it clear that the true ‘thought’ or content of ancient Greek oral epos dwells in the remembered traditional formulaic and stanzaic patterns rather than in the conscious intentions of the singer to organize or ‘plot’ narrative in a certain remembered way

Song is the remembrance of songs sung.

Copia

Copia as a writing exercise refers to a deliberate practice of finding the many ways in which one might say something

Round vs flat characters. Round characters are a production of effective narrative or drama, offering complexity and surprises vs. a flat character, derived from primarily oral narratives that rarely delights by fulfilling expectations copiously.

All these developments are inconceivable in primary oral cultures and in fact emerge in a world dominated by writing with its drive toward carefully itemized introspection and elaborately worked out analyses of inner states of soul and of their inwardly structured sequential relationships.

Writing and reading engage the psyche in strenuous, interiorized, individualized thought of a sort inaccessible to oral folk. In these private worlds, the feeling for the round human character is born, deeply interiorized in motivation, powered from within.

Writing and print do not give away with the flat character. The Jolly Green Giant works well enough in advertising script because the anti-heroic epithet ‘jolly’ advertises to adults that they are not to take this latterday fertility god seriously.

Theorems

Orality is not an ideal, and never was. To approach it positively is not to advocate it as a permanent state for any culture. Literacy opens possibilities to the word and to human existence unimaginable without writing. Oral cultures today value their oral traditions and agonize over the loss of these traditions, but I have never encountered or heard of an oral culture that does not want to achieve literacy as soon as possible. (Some individuals of course do resist literacy, but they are mostly soon lost sight of.) Yet orality is not despicable. It can produce creations beyond the reach of literates.

Misc Summarizations

-

” Additive rather than subordinative: Oral cultures use less structure than written cultures and are not as concerned with the rules of grammar as much as literate cultures. They express themselves by appending their thoughts together in a pragmatic manner. (Ong, p.37)

-

Aggregative rather than analytic: Oral cultures use formulaic oral expressions to make expressions more meaningful and memorable. (Ong, p.38)

-

Redundant or copious: Oral cultures repeat information so that it becomes ingrained in memory. (Ong, p.39)

-

Conservative or traditionalist: Oral cultures repeat information over and over again to ingrain the information and avoid adding any extra information as it would be too much of a burden to remember. (Ong, p.41)

-

Close to the human lifeworld: Oral cultures remember information that is familiar to their surroundings and their own life experiences. (Ong, p.42)

-

Agonistically toned: Oral cultures remember dramatic events that have a tone that expresses drama and agony. (Ong, p.43)

-

Empathetic and participatory rather than objectively distanced: Oral cultures prefer being close to their audience where the audience and the speaker each have influence over each other. (Ong, p.45)

-

Homeostatic: Oral cultures retain information that pertains to their current situation, not dwelling on the past. (Ong, p.46)

-

Situational rather than abstract: Oral cultures learn about ideas and concepts that actually exist. (Ong, p.49)”

-

Writing is a “deception” in that it “makes speech permanent.” Written words are time-bound and performative; speech is impermanent

-

Today, we tend to view writing as totally interiorized, a mental process, inseparable from humans. Ong calls it a “technology,” just like printers and computers

-

Writing is a technology that allows us to render permanent (and more or less immutable) impermanent language

-

Argues that while speech is “natural,” writing is “artificial”

-

Writing allows us to achieve deeper, more complex thinking not made possible through speech—it is an interior transformation of consciousness. It is an external technology that becomes interiorized.

-

Writing promotes “separation” in several ways:

-

The “known” from the “knower,” which produces the illusion of “objectivity”: provides a set of marks that a knowing subject can interpret, thereby generating knowledge

-

Separates interpretation from data: a text is a piece of data separate from the writer and the reader, so its meaning isn’t “fixed” by anyone, but by the text itself

-

Distances word from sound

-

Distances the source of the text (author) from the reader in both time and space

-

Writing separates (written) language from its immediate context; allows language to transcend time, space, and any particular context

-

Because writing is split from context, it forces a sort of precision typically lacking in oral speech, as meaning is always context-dependent. Writing also doesn’t afford non-verbal markers of meaning, such as facial expressions, body language, sighs, etc.

-

Writing separates past from present; it preserves words, forms of expression, and “puzzles” no longer immediately accessible in the present

-

Separates “administration” (civil, religious, commercial, etc.) from other kinds of activities

-

Makes it possible to separate logic (thought structure of discourse) from rhetoric (socially effective discourse)

-

Separates academic learning from wisdom, making it possible to convey highly organized and abstract thoughts independent of their actual use or integration into the “real” world

-

Can help split verbal communication into “high” (academic, religious, etc.) and “low” (common) registers (even gendered registers)

-

Writing makes our pool of words—our vocabularies—MUCH bigger than orality alone. In fact, writing necessitates the production of words in print (that is, type); (as Ong says, imagine writing the dictionary by hand)

-

Writing divides/distances more evidently as its forms become more abstract. Alphabets tend to be more abstract than pictographs.

-

Writing separates being from time. Deep philosophical and scientific thinking requires backtracing, revising, and “talking to” previous work—made possible only through writing and archiving

-

Oral speech is good for narrative, but philosophy (which only emerged through writing) is anti-narrative; it creates abstract nouns with no referents in the “real” world

-

The verb “to be” (and other verbs emphasizing relationships) become more important than “action verbs”

-

The computer radically separates the knower from the known