created, $=dv.current().file.ctime & modified, =this.modified

tags:literature

It is not so pertinent to man to know all of the individuals of the animal kingdom, as it is to know whence and whereto is this tyrannizing unity in his constitution, which evermore separates and classifies things, endeavoring to reduce the most diverse to one form. - Ralph Waldo Emerson

Introduction VermiCulture

Humans have adopted for centuries the misguided idea that we are somehow better, more valuable than them.

By looking at how man organizes and represents his encounters with the worm, we will see how necessary it is to recalibrate the definitions and aesthetic valuations we assign not only to this lowly being but to ourselves.

She’ll avoid serpents and reptiles, particularly the mythological like the dragon and wyrm. The study is warranted but the mystical connotations would steer the project away from foundations in empiricism and organic matter. Also these creatures are more complex in contrast.

- Chapter 1 - Transitional Tropes: The nature of life in European Romantic Thought

- Ground the analysis in this book to object of natural history and their representative studies and figurative effects. The worm as an agent of change integral to and transformative of both matter and mind.

- Chapter 2 - Unchanging but in Form Erasmus Darwin

- Extended reading of Darwin’s final poem The Temple of Nature: or, The Origin of Society

- The poem reveals how empirical pursuit gives way to an aesthetic consciousness reliant on figures and twoneess to represent material oneness.

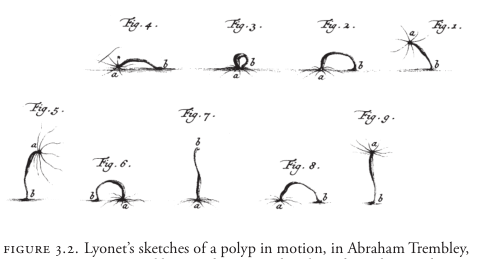

- Chapter 3 - Not without some repugnancy, and a fluctuating mine: Trembley’s Polyp and the Practice of 18th Century Taxonomy

- Returns to natural history writing to illustrate ad kind of lyricism and aesthetic revaluation built into the articulation of empirical study. Focusing on the freshwater hydra, that displayed an astonishing variety of wormy behaviors, including the capacity to regenerate from cuttings as if it were a plant.

- Chapter 4 - Art Thou a Worm? Blake and the question of taxonomy

- the worm as an aesthetic figure made to represent the material consequences of existing in nature and how Blake’s poetry gives way to a positive aesthetic of decay.

- Chapter 5 - Diet of Worms, Frankenstein and Vile Romanticism

- Natural history reading of Frankenstein

- Conclusion: Wherefore All This Wormy Circumstance

- examination of Keats Isabella; or the Pot of Basil and Darwins The Formation of Vegetable Mould, through the action of Worms with Observations on their Habits

Transitional Tropes

Jane Bennnet’s Vibrant Matter and Timothy Morton’s The Ecological Thought present a complementary philosophical treatment of ecology that lends itself to prescriptive de-centering of the human.

Bennet asks to ascribe a vital agency to material things as we would to particular beings, like ourselves.

Worms are the ur-plough, preparing the land for all types of growth.

When we behold a wide, turf-covered expanse, we should remember that its smoothness, on which so much of its beauty depends, is mainly due to all of the inequalities having been slowly leveled by worms. It is a marvelous reflection that the whole of the superficial mould over any such expanse has passed, and will pass again, every few years through the bodies of worms.

The Ecological thought realizes that all beings are interconnected. The ecological thought realizes that the boundaries between, and the identities of, being are affected by his interconnection. This is the strange stranger.

Spontaneous Generation: Transmutation and Transformation

Belief in spontaneous generation, began with an observation of insect behavior. Aristotle claimed that worms, or vermes, were brought forth by the putrefaction of social and organic matter under the influence of rain. Descartes replaced the influence of rain with heat.

Francesco Redi claimed that all dead flesh… are but a good breeding ground for eggs of flies and other winged animals. Through experiments on frog flesh, he refuted spontaneous generation.

He was unaware of metamorphosis of maggots into flies, but helped distill the empirical direction.

The study of worms threatened organic collapse, but investigation and experimentation of worms, endangered the natural theological belief that held the proof of God’s existence (rooted in spontaneous generation.)

Linnaeus believed in the proclivity of man to classify those objects placed within his field of vision. He states “natural objects belong more to the field of the senses than all of the others and are obvious to our senses anywhere.” In doing so he highlights the limited vision of any system-making endeavor including his own.

Unchanging but in Form

Erasmus Dawin was the definition of an 18th century interdisciplinarian: his interests, always forward thinking, cross through a mixture of fields and their methodologies. The “scientist-poet” and “poet-naturalist.”

The Temple of Nature: or, the Origin of Society (1803) his final work, is the focus of this study.

By filtering the elements of natural history through the body of poetry, Temple transforms unfathomable nature into a sound cultural artifact. This fundamentally vermicular activity projects in turn the challenge and necessity of representing the natural world as an aesthetic work, that is, within the space of literature. It relies paradoxically on decompositional processes, on the productive dismantling of an apparent organicism, to compose an aesthetic epistēmē wherein figures of twoness represent a material oneness.

He wrote The Loves of the Plants with a goal to “enlist Imagination” under the banner of Science, this parodic poem offered sexualized images of flora after the fashion of Linnaean classification in an effort to restore a shared sense of animality between all animate things.

Not without some repugnancy, and a fluctuating mind

Having noticed various small animals on the plants that I had taken from a ditch, I put some of these plants into a large jar filled with water, placed it on the inside sill of a window, and then set about examining the creatures that it contained… . The novel spectacle presented me by these little animals excited my curiosity. As I scanned this jar teeming with creatures, I noticed a polyp fastened to the stem of an aquatic plant. At first I paid little heed, for I was following the livelier little creatures which naturally attracted my attention more than an immobile object.

Polyps of a “pretty green color” identified initially as plants because of their likeness to surrounding flora. Owing to their shape, their green color, and their seeming immobility, the polyps were likened to bits of grass or the tufts of dandelion seed. Transmutation and Transformation

I expected to see their arms and even their bodies merely shaken or dragged along with the motion of the water. Instead I saw the polyps contract so suddenly and so forcefully that their bodies looked like mere particles of green matter and their arms disap- peared from sight altogether. I was caught by surprise. This surprise served to excite my curiosity and make me doubly attentive.

It] made me think of cutting up the polyps. I conjectured that if a polyp were cut in two and if each of the severed parts lived and became a complete polyp, it would be clear that these organisms were plants. Since I was much more inclined to think of them as animals, however, I did not set much store by this experiment; I expected to see these cleaved polyps die.

It seemed natural enough to me that the half of the polyp composed of the head and a portion of the body could still live. I thought that the operation which I had performed had only mutilated the head part without disrupting its animal economy. I compared this first part to a lizard which has lost its tail and which does not die from losing it. Indeed, again supposing that the polyp was an animal, I assumed that the second part was only a kind of tail without the organs vital to the life of the animal. I did not think that it could survive for long separated from the rest of the body. Who would have imagined that it would grow back a head!

Rather than die, the polyp multiplied. One polyp became soon became two complete, functioning polyps.

According to the original reasoning behind this experiment I would have to conclude positively that the polyps were plants, and moreover, plants which could grow from cuttings. Nevertheless I was very far from hazarding such a decision. The more I observed whole polyps, and even the two parts in which the reproduction just described took place, the more their activity called to mind the image of an animal. Their movement seemed spontaneous, a characteristic always regarded as foreign to plants, but one with which we are familiar through endless examples among animals. Everything I had done to extricate myself from doubt had served only to plunge me deeper into perplexity.

I do not dare to give it a name, although this would be very convenient. That of animal plant or plant animal presents itself rather naturally.

He classifies them as animals upon seeing them ingesting flies, ironically later in 1760, in North Carolina the “catch fly sensitive” later known as the Venus flytrap is discovered.

Abraham Trembley’s notorious experiments with the fresh water polyp during the 1740s had set the biological world agog. In defi- ance of reason, he demonstrated that an organic chit or speck could regenerate into a whole and healthy organism. Scientists subsequently engaged in a frenzy of amputation: segmented earth- worms, horned slugs, footed snails, limbed toads and frogs were variously lopped to test their regenerative capacities… . These unruly and colorful fragments were thus responsible for making a new aspect of the invisible visible.

Art thou but a worm?

Eighty-eight worm references are present in William Blake’s textual oeuvre, from earthworm, glowworm, silkwork, and tapeworm.

Worm in the Blake Dictionary is described as

the lowest and weakest form of animal life, a simple alimentary tube without any means of self-defense.

“living things reach their fullness and die after preparing the way (organically and reproductively) for new living things, new forms of organic life.

To unknowingly recognize herself as worm food is finally to align herself with the nourishing roles performed by the Lilly and the Cloud and, by extension, the whole of the natural world.

A diet of Worms, Frankenstein

I saw how the fine form of man was degraded and wasted; I beheld the corruption of death succeed into blooming cheek of life; I saw how the worm inherited the wonders of the eye and brain - Victor Frankenstein

“it may be the case that science and poetry are incompatible, that the ascendancy of the former will mean the ultimate extinction of the latter.” - Clark Emery

man has lost / his desolating privilege and stands / an equal amidst equals