created 2025-05-27, & modified, =this.modified

rel:Prehistoric Digital Poetry - C.T. Funkhouser Turing Cathedral by George Dyson

Why I’m reading

Further reading on these early computer art experiments. I love someone can look at a mainframe (which weight-wise seems the opposite of a song) and maybe want a song to be made from it.

Right now, for obvious reasons, AI art is maligned, particularly within the traditional art crowd. But the text back then, often optimistically can be interpreted as pointing towards the “promise” (however unfounded) of AI or more fully computer generative art.

In the introduction I see quotes Cage

What we need is a computer that… turns us… not “on” but into artists.

I found the full quote, which seems to be talking about viewing computers as a medium from 1986.

“What we need is a computer that isn’t labor-saving but which increases the work for us to do, that puns (this is McLuhan’s idea) as well as joyce (this is Brown’s idea) revealing bridges where we thought there weren’t any, turns us (my idea) not ‘on’ but into artists.”

The full quote informs a bit more, “labor-saving.”

Subheading - Early Computing and the Foundations of the Digital Arts Edited by Hannah B Higgins and Douglas Kahn

The book covers the time frame of room sized mainframes of the 50s, to the 70s with the transition to microcomputers.

Radical and experimental aesthetics and political and cultural engagements of the period across many individuals, groups and institutions can stand as a historical allegory for the mobility among tech platforms, artistic forms, and social sites that are common today.

1966 Cage posed a question, “Are an audience for computer art?”

The answer’s not No; it’s Yes. What we need is a computer that isn’t labor-saving but which increases the work for us to do, that puns (this is [Marshall] McLuhan’s idea) as well as Joyce revealing bridges (this is [Norman O.] Brown’s idea) where we thought there weren’t any, turns us (my idea) not “on” but into artists

Cage talks about the labor required of both the artist and the engineer, creating the mainframe artist – creatively engaged with the emerging technology.

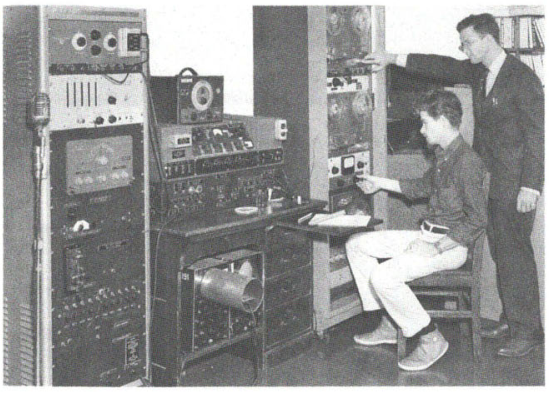

From 1955 to 1957, Le-jaren Hiller, a former chemist, used a mainframe at the University of Illinois to collaborate with Leonard Isaacson on the composition Illiac Suite for String Quartet. The vacuum-tube computer, weighing five tons and with miniscule memory, was used to generate the notation rather than synthesize the sounds, and the overriding purpose of the project was to technologically regenerate existing musical aesthetics.

In 1967 Tenney gave an influential FORTRAN workshop for a group of composers and Fluxus artists that included Steve Reich, Nam June Paik, Dick Higgins, Jackson Mac Low, Joseph Byrd, Phil Corner, Alison Knowles and Max Neuhaus.

The first display devices were special purpose types primarily provided for the military.” As you will know, the first prizewinners in the now annual computer art contest held by “Computers and Automation” were from a U.S. ballistic group. There is little doubt that in computer art, the true avantgarde is the military

James Tenny was at Bell Labs – a sentiment of anti-war:

Still, as the 1960s progressed, antiwar sentiments intensified and institutional clashes became more pronounced. In 1967, not long after the FORTRAN workshop, while addressing faculty members and representatives from the military at the Poly- technic Institute of Brooklyn, Tenney chose to play his Fabric for Ché, based on Che Guevara, who had been captured and killed in Bolivia the same year, as his way to say “something about my disgust about the war in Vietnam.

“The contents of works produced by Kenneth Knowlton at Bell Labs are shockingly dull images of gulls aloft or a telephone on a table or a female nude rendered in symbol set.”

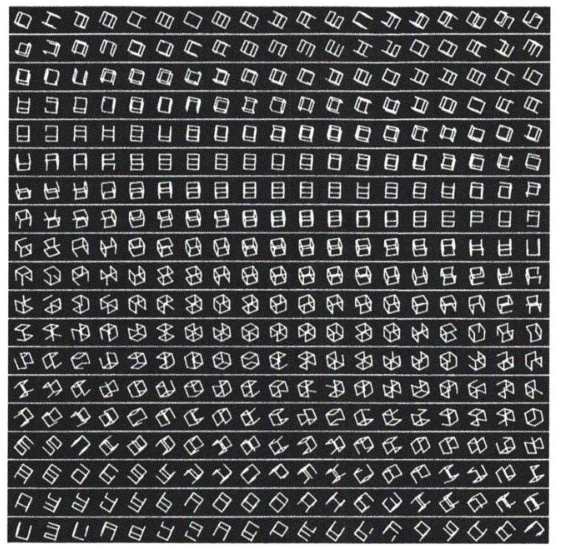

Labs. In 1963, Knowlton developed the BEFLIX (Bell Flicks) programming language for bitmap computer-produced movies, created using an IBM 7094 computer and a Stromberg-Carlson 4020 microfilm recorder. Each frame contained eight shades of grey and a resolution of 252 x 184. In 1966, Knowlton and Leon Harmon were experimenting with photomosaic, creating large prints from collections small symbols or images.

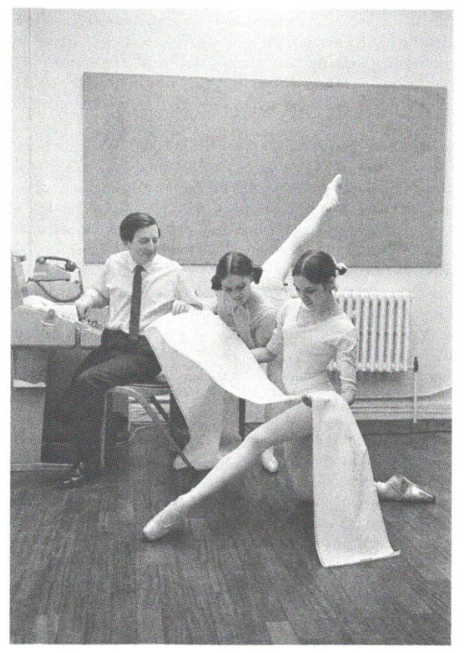

In Studies in Perception I they created an image of a reclining nude (the dancer Deborah Hay), by scanning a photograph with a camera and converting the analog voltages to binary numbers which were assigned typographic symbols based on halftone densities. It was printed in The New York Times on 11 October 1967, and exhibited at one of the earliest computer art exhibitions, The Machine as Seen at the End of the Mechanical Age, held Museum of Modern Art in New York City in 1968.

The Soulless Usurper

Mechanistic muses are expanding their domain to encompass every facet of creative activity. - J. R. PIERCE, ” Portrait of the Machine as a Young Artist, 1965

On early computer generated art:

Some saw it as just another example of the vulgarization of science, in which besotted artists, flirting with the latest scientific and technological media, produced what was tantamount to scientific kitsch

NOTE

Sine Curve Man by Charles Csuri and James Shaffer, the winner of Computers and Automation’s 1967 contest

Connections to Futurism?

The prize-winning art piece, Splatter Diagram, which was printed on an early printer called a dataplotter, was a design analogue of the radial and tangential distortions of a camera lens/ In 1964, the same laboratory won first prize for an image produced from the plotted trajectories of a ricocheting projectile. The uncomfortable knowledge of computer art’s mili- tary origins has prompted many commentators and proponents to situate the emergence of computer art a number of years after 1963, effectively bypassing its military birthplace.

These objects were modeling natural phenomenon, such as the trajectory of ricocheting projectiles. The aesthetic appeal was a byproduct of these utilitarian causes.

An exhibition was shown Computer-Generated Pictures. AT&T had doubts about how this would be perceived:

Although the research management staff at Bell Labs was very supportive of the Howard Wise Gallery exhibit, the legal and public relations folks at AT&T became worried that the Bell Telephone companies that supported Bell Labs would not view computer art as serious scientific research. Hence an effort was made by AT&T to halt the exhibit, but it was too late, since financial commitments had al- ready been made by Wise.

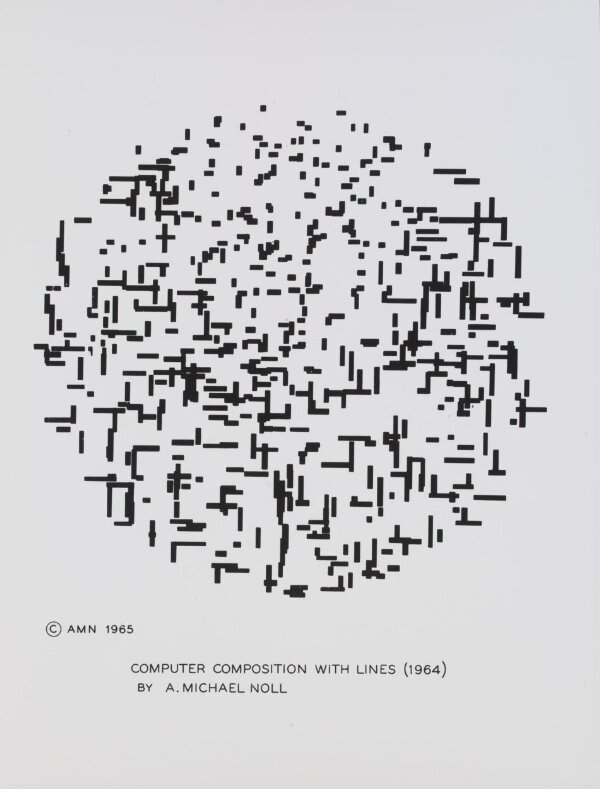

When Noll attempted to copyright his piece Gaussian Quadratic (1962) he was refused on the grounds that a machine had generated the work.

Noll then explained a human being had written the program, but LoC stated randomness was not acceptable criterion. Finally he was granted when he explained that although numbers generating the program appeared random to human, the algorithm was mathematical and not random at all.

Noll then explained a human being had written the program, but LoC stated randomness was not acceptable criterion. Finally he was granted when he explained that although numbers generating the program appeared random to human, the algorithm was mathematical and not random at all.

The Wise gallery was a landmark but was described as bleak, cold and soulless – “with the same aesthetic appeal” as “the notch patterns on IBM cards”. None of the works were sold at the exhibition.

The cube was devoid of subjective overtones, the least emotive of geometric forms.

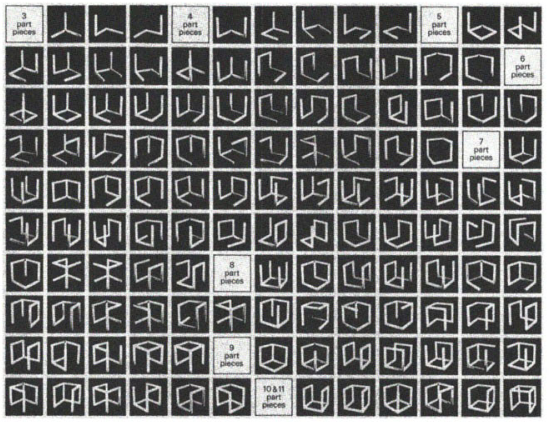

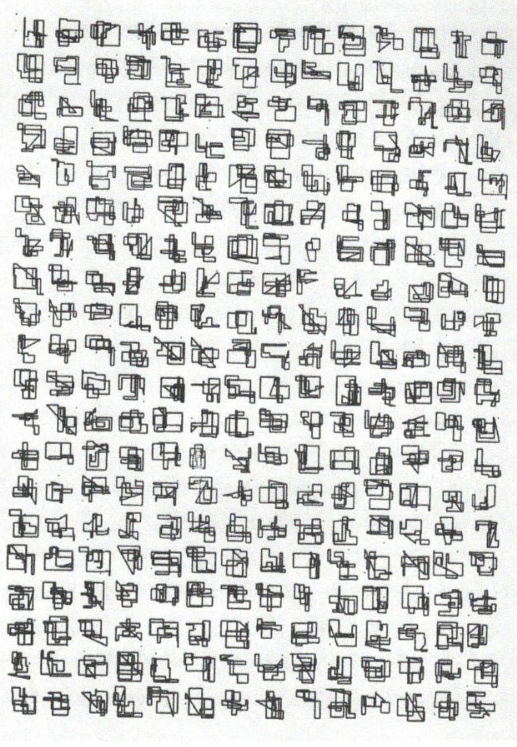

Producing a system that was prefigured, yet visually unpredictable and autonomous was consistent with the aims of LeWiit and Mohr.

LeWitt – “idea becomes a machine that makes the art.”

Stuart Preston, covering the Wise Exhibit for the NYT, discussed the fears of mechanized creativity, such that science and tech would control the future to the point that any painting, would be computer computer generated.

Mechanical automata, such as Jacques de Vaucanson’s eighteenth-century robotic flute player, drummer, and duck, inspired a whole spectrum of emotions, from wonderment at the machine’s lifelike motion to extreme indignation over the Promethean powers it seemed to engender.

Many technologists explicitly promoted the idea of man vs. machine.

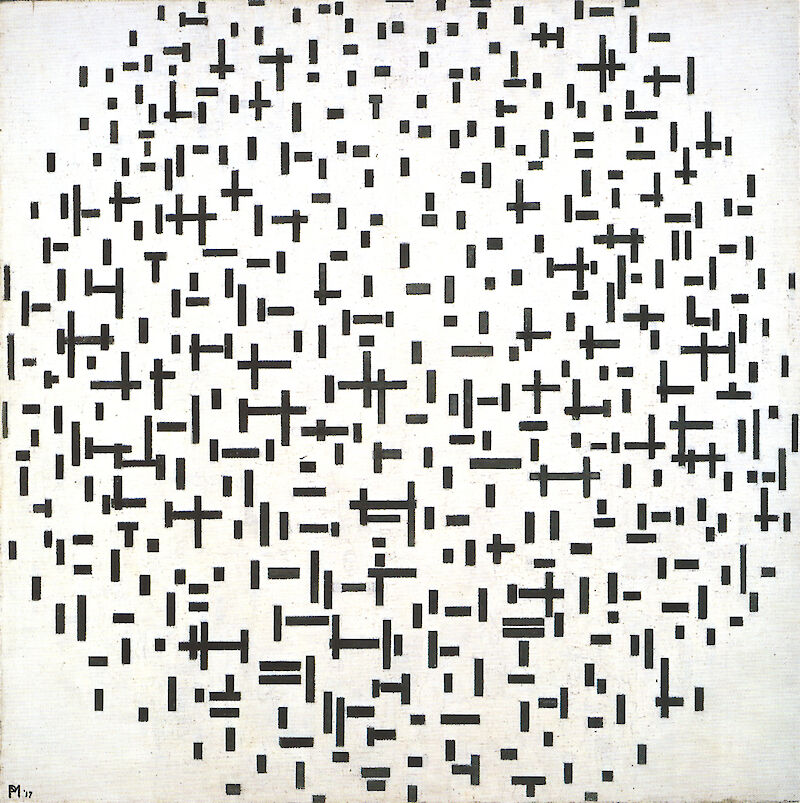

Noll completed a now famous experiment whose results showed that his computer-generated Computer Composition with Lines (1965) was preferred by an audience to Piet Mondrian’s Composition with Lines (1917)

The computer threatened to invade the territory of the artist, bring a mathematization of art, and make fine art no longer the “domain of the artistic genius” who, as Kant suggested had “a talent for producing that for which no definite rule can be given.”

Georges Perec’s Thinking Machines

rel: An Attempt At Exhausting a Place In Paris by Georges Perec Oulipo

Georges’s concept of a thinking machine played a significant role in his development as a writer, as served as a model for his most experimental work, despite him not encountering a computer.

He said he was a writer, with no imagination to speak of. Writing was like work, and like any other industry it was the product of labor and machinery.

In 1966, with his friend Marcel Bénabou, he struck on a semiserious, theoretically challenging translation device for the automatic production of literature, which they called P.A.L.F. (for production automatique de littérature française).

Semantic Poetry by Stefan Themerson: Take a line: “I wandered lonely as a cloud…” and replace each noun with its dictionary definition, “I wandered lonely as a mass of watery vapor suspended in the upper atmosphere”

P.A.L.F. makes translation by semantic definition a recursive device, and quickly produces monstrously inflated expressions that tend asymptotically toward the inclusion of all the words in the lexicon.

Any text subject to the automatic production device, tended toward exhaustion of the lexicon, and any two texts would at some point of expansion to come include the same words as each other.

P.A.L.F. would thus be able to show that, in the last analysis, everything has the same meaning.

The logic isn’t impeccable and leaves syntax aside, but it offered “the young subversives the heady prospect of creating philosophical havoc.”

What they found was that the device was not as automatic as all that: dictionaries characteristically provide more than one definition for a word, and so choices must be made; as the “translation” proceeded, more and more common words with multiple definitions invaded the text; and they dropped the project long before reaching the hypothetical supersize.

Constraint: “A constraint is any operation that can be made fully explicit on some level or another of a language (sound, letter, word, sentence… ) and which gives rise to a new text.”

“A Void,” a novel of three hundred pages written without the help of the letter e (the constraint being to write with only twenty-five letters, but within the grammar and lexis of the standard language nonetheless)

Computers at this time were able to fingerprint texts on the basis of average sentence length, word frequency; this was attractive to Oulipo due to the idea it was possible to identify ownership via algorithm and in the reverse, produce synthetic text indistinguishable from the authentic material.

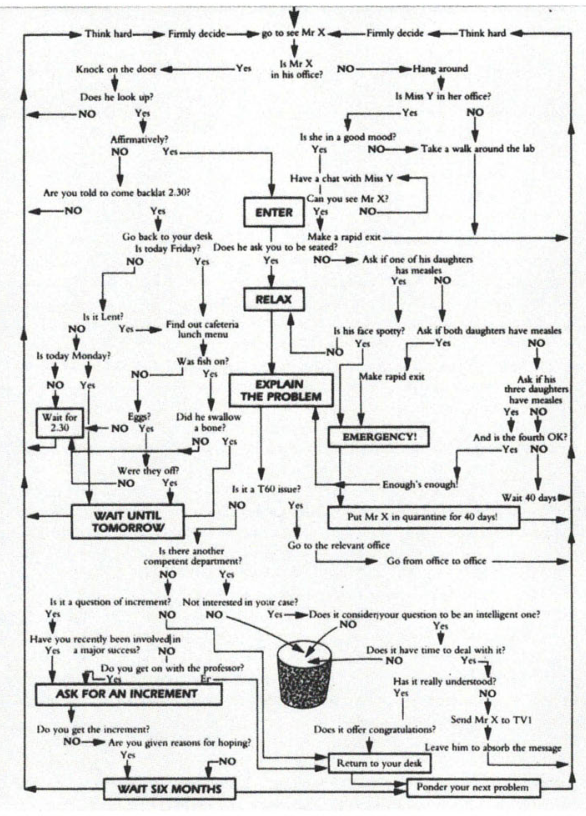

A flowchart, as Perec explained, shows simultaneously all the steps and the order of their recursion in a set of instructions. It also contains within it all the possible moves allowed by the algorithm. But human life is finite, and after each loop of the flowchart, the decision maker is a bit older. This brings him back to the key of life and poetry, namely death.

The theory of the Clinamen, insofar as it relates to Perec’s work, is that intentional irregularity softens the harshness of a text written under constraint, bringing all-too-human fallibility into the domain of formal art. It’s a way of having your cake and eating it too, for a clinamen is not an example of fallibility, but an intentional bending of self-imposed rules to show that the writer is in complete command not only of necessity, but also of chance.

Thought

Looking for more information on P.A.L.F

In Forming Software - Software, Structuralism, Dematerialization

rel:Software Information Technology Its New Meaning for Art, catalogue 1970

Jack Burnham anticipated the two-way communication between mind and machine, and the art that would evolve as a result of this:

The computer’s most profound aesthetic implication is that we are being forced to dismiss the classical view of art and reality which insists that man stand outside of reality in order to observe it, and, in art, requires the presence of the picture frame and the sculpture pedestal. The notion that art can be separated from its everyday environment is a cultural fixation [in other words, a mythic structure] as is the ideal of objectivity in science. It may be that the computer will negate the need for such an illusion by fusing both observer and observed, “inside” and “outside.” It has already been observed that the everyday world is rapidly assuming identity *with the condition of art.

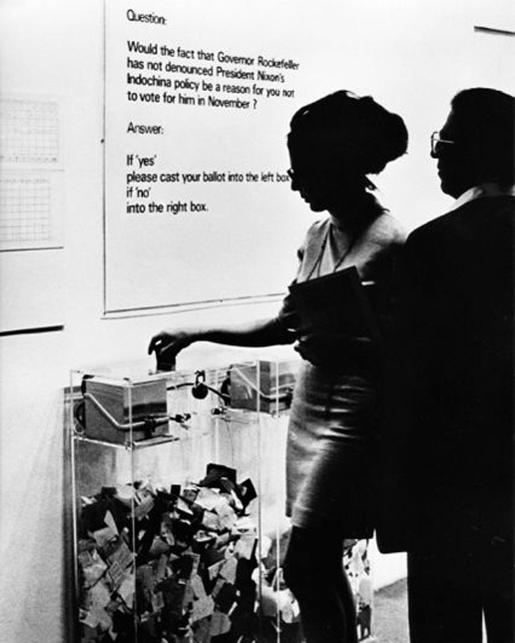

Hans Haacke utilized technology and mass media in work that is fundamentally conceptual in nature but contributes to the discourses of multiple artistic tendencies. Perhaps best known for his politically charged critiques of power relations among individuals, art institutions, industry, the military, and government, Haacke’s work in the early 1960s evolved from kinetic sculpture.

Visitor profile: Haacke was planning a museum that would produce a steady output of statistical information about visitors involving a small processor-controlled computer and a display device.

There was a questionnaire about politically provocative questions, and instantaneous statistical results. A teletype terminal with a monitor was connected to a time-sharing computer, programmed to cross-tabulate demographic information about the visitors (age, sex etc) and questions (assuming you were indochinese, would you sympathize with the present Saigon regime?)

This information of visitor profiles would be projected onto a large screen, accessible to a large number of people.

Although Burnham blamed the programmer, rumors circulated ranging from sabotage to a custodian accidentally causing the computer to malfunction. Technical difficulties had beset many major art and technology exhibitions

rel: Blur

Information Aesthetics and the Stuttgart School

Max Bense and Abraham A. Moles between 1956 and 1958 tried to bridge philosophy, psychology, aesthetics, social sciences, and art theory.

The goal was to develop a theory that would allow one to measure the quality of info in aesthetic objects, thus enabling evaluation of arts beyond “art historian chatter.” A numerical value of the object itself.

Bense focused on entropy, process and co-reality while Moles focused on aspects of perception and psychology.

M = O x C

Georg Nees attempted to draw using a punch hole controlled drawing table, and a calculating machine to produce aesthetic disturbance.

Bense (who was influenced by Hegelian thought, after all) saw in the general development of art the process of negentropy, a progression toward order, while the physical world heads toward chaos.

James Tenney at Bell Labs

In his presidential farewell Eisenhower celebrated that for each blackboard there now existed hundreds of new computers. But he also warned of capture by the technological elite and a military-industrial complex.

In his presidential farewell Eisenhower celebrated that for each blackboard there now existed hundreds of new computers. But he also warned of capture by the technological elite and a military-industrial complex.

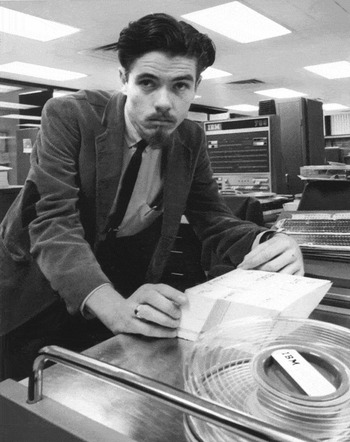

Tenney was the first composer to work in a sustained manner with digital sound synthesis.

In his master’s thesis Meta/Hodos, Tenney proposed a theory that major works of 20th century western music could be understood as a product of a deeper reign of speech, not merely as an evolution of musical form. This aligned with Bell Labs’ historical mission with respect to speech synthesis.

Tenney arrived at Bell Labs with a “dissatisfaction with all purely synthetic electronic music that I had heard up to that time, particularly with respect to timbre.” How often have you heard a synthesized sound you liked?

With computer music, on the other hand, the composer became an instrument builder in the course of programming a composition.

He would walk around NYC listening to sounds and ask himself how could I generate that?

Misc. Bell Labs from other sources

While scientists used an IBM 704 to calculate the position of Sputnik, Max Mathews used the same computer to compose melodies.

Arthur Samuel taught an IBM 701, nicknamed “Defense Calculator” how to play checkers.

In the 1950s, Bell Labs was at the height of its powers – a singular and peculiar American institution that seemed to have a hand in every major scientific discovery of the 20th century. Researchers at Bell Labs had discovered the transistor, launched the field of information theory, invented the photovoltaic cell and built the first digitally scrambled speech transmission system, among other things.

Bell Labs was simultaneously becoming an unlikely center for pioneering computer music, art, film and animation. In the 1960s and 1970s, prominent composers such as John Cage, James Tenney and Edgard Varèse would visit Bell Labs to work on ideas.

HPSCHD – Ghost or Monster?

HPSCHD was a multimedia performance created by John Cage and Lejaren Hiller with the use of the ILLIAC II supercomputer, performed in 1969.

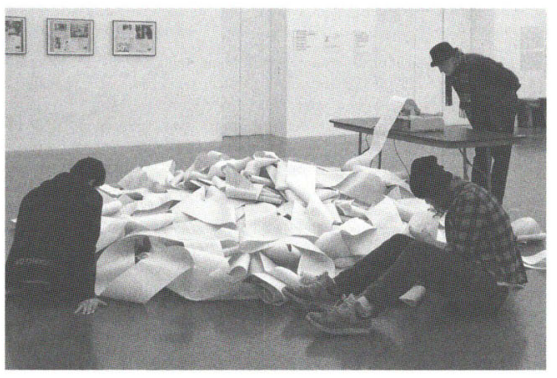

The performance allowed the audience (estimated at some seven thousand people) to circulate freely amid a willfully chaotic performance that consisted of seven amplified harpsichord soloists and fifty-two amplified tape recorders.

For the HPSCHD program, Cage and Hiller, partly for acoustical reasons and partly for reasons dictated by available memory space in the IBM computer they used, divided the octave in all ways from 5 to 56. For each of these mathematically obtained pitches they gave a field of sharping and flatting by any of sixty-four ICHING determined degrees. This results in a potential reservoir for HPSCHD of approximately 885,000 pitches

The scale is so broken into small components that it at times the listener cannot detect the difference.

HPSCHD’s ambition was to figure no less than the totality of existence, from the microscopic realm (microtonal music) through the macroscopic (outer space visuals), with the audience and participants situated in between.

HPSCHD is composed of 7 solo pieces for harpsichord and 52 computer-generated tapes. The harpsichord solos were created from randomly processed pieces by Mozart, Beethoven, Chopin, Schumann, Gottschalk, Busoni, Schoenberg, Cage and Hiller, rewritten using a FORTRAN computer program designed by Ed Kobrin based on the I Ching hexagrams. Cage had initially turned down the commission (stating that he hated harpsichords because they reminded him of sewing machines) but Hiller’s proposal reignited his interest in the piece, which provided an interesting challenge for both Cage’s chance experiments and Hiller’s use of computer algorithms in musical composition.

The Alien Voice

NATC is among the first musical applications of the Vocoder, but the device itself already had a rich history. In 1928 Homer Dudley a telephone engineer at Bell Labs tried to solve how to compress broadband speech signals for transport across a very narrow bandwidth of transatlantic telegraph cables.

body-instrument Dudley recognized speech could be separated into two components:

- the sound source (produced by vibrating vocal cords)

- and its modulation (by the nose, throat, tongue and lips) So his solution was not to transmit an adequate version of the two components, and reconstruct that on the receiver end.

The result of this was the Voice operate reCOrDER or Vocoder which was patented in 1935.

With the ability to translate speech into code, the Vocoder was used in military encryption.

Turing at Bell Labs working on SIGSALY

SIGSALY used a random noise mask to encrypt voice conversations which had been encoded by a vocoder. The latter was used to minimize the amount of redundancy (which is high in voice traffic), in order to reduce the amount of information to be encrypted

I Am Sitting in a Room (1970), Lucier’s most famous composition. The score calls for a speaker to read and record a short text that reflexively lays bare the procedure of the piece:

I am sitting in a room different from the one you are in now. I am recording the sound of my speaking voice and I am going to play it back into the room again and again until the resonant frequencies of the room reinforce themselves so that any semblance of my speech, with perhaps the exception of rhythm, is destroyed. What you will hear, then, are the natural resonant frequencies of the room articulated by speech. I regard this activity not so much as a demonstration of a physical fact, but more as a way to smooth out any irregularities my speech might have.

Alvin Lucier

In 2025, a new musical exhibit based on cerebral organoids cultured from Lucier’s white blood cells was opened at the Art Gallery of Western Australia. The cerebral organoids made from Lucier’s DNA emitted electrical signals that triggered various mallets connected to brass plates, creating music. Lucier voluntarily arranged for the project so that he could continue to create music after his death.

NATC

NATC goes further than “I am sitting…” explicitly reflecting on the alien nature of speech, language and communication.

According to philosophical tradition, speech is intimately tied to being and presence—specifically, to one’s own being and self-presence. Our speech announces and affirms our living, physical existence and our conscious, mental intentions. Emanating from our very bodies as breath and vibration, speech is the expression of our inferiority— the discourse of the soul, as Plato called it…

Even speech, then, is a technology, a prosthesis. Writing is even more evidently so. Our written signs bear no natural relationship to our spoken sounds (which, by the same to- ken, bear no resemblance to their meanings). Cast adrift from us, they are able to (indeed, are built to) signify even in our absence or after our deaths. Due to this structural alienation from our physical presence and animating intentions, the written sign can be understood in ways we never intended and drawn into con- texts we never imagined or sanctioned. This is no less true of audio recording or phonography (literally, voice- or sound-writing). While it promises a return to

(Hartford) Memory Space (1970) – each member of a group of performers travels to a designated place int he city to record the sound of that space, then recreate the sound in a concert (by voice or instruments) simultaneously with the others.

Lucier:

I wanted [the performers] to stick as closely as possible to their remembrance of the environment, so I isolated [them] from one another. It was as if each of them were on an island but the audience could see and hear all those Islands. The islands could be parts of the town, or places in the streets, and the audience would see and hear a composite of which the individual players were only a part.

House of Dust

rel: Prehistoric Digital Poetry - C.T. Funkhouser Absence of Clutter - Minimal Writing as Art and Literature

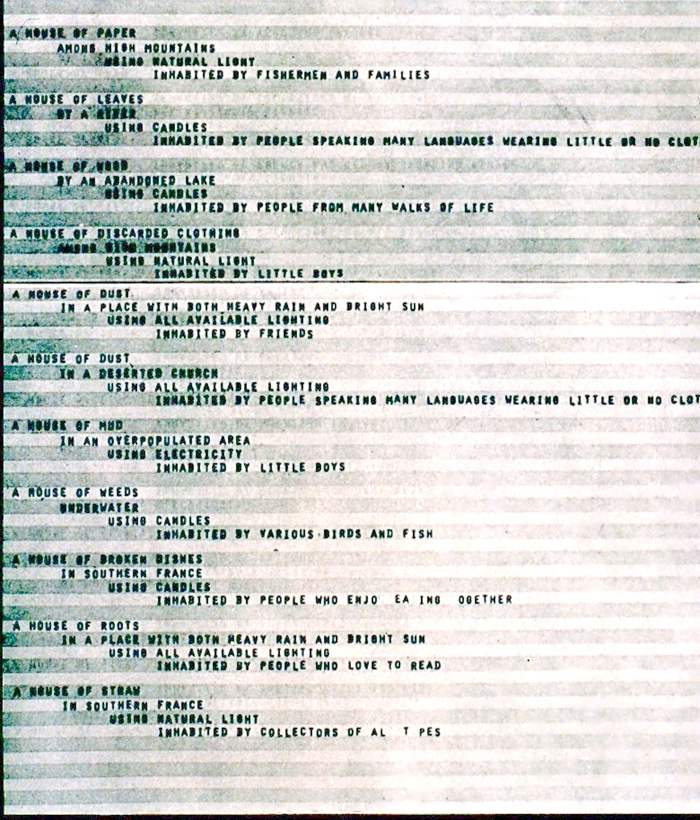

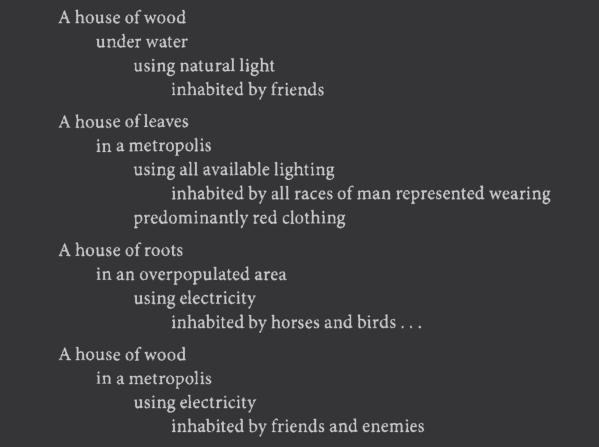

With the help of James Tenney, Alison Knowles produced her benchmark computerized poem, House of Dust. It consists of four lists beginning with the “a house of” followed by a randomized sequence of material, a site or situation, a light source or category of inhabitants. It was programmed in FORTRAN IV.

Thought

Do, or see if there has been a recreation of HoD which actually constructs a depiction of the generated house. Even, I wonder if a generative physical house that conjured the atmosphere could be made? I imagine it like a diorama, a miniature play stage shifting.

Computer Participator

rel: Nam June Paik - Video Time Space

Paik’s goal with the early works is greater audience participation. He developed “participation TV” starting with manipulated television sets. He set out to transform the dross of commercial mass media to something that could dialogue with the high-modernist avant-garde. “I always thought television was a great medium, but I hated the mass media part.” He wanted to combat idle watching.

From 1967 through 1968, Paik was a residential researcher at Bell Labs.

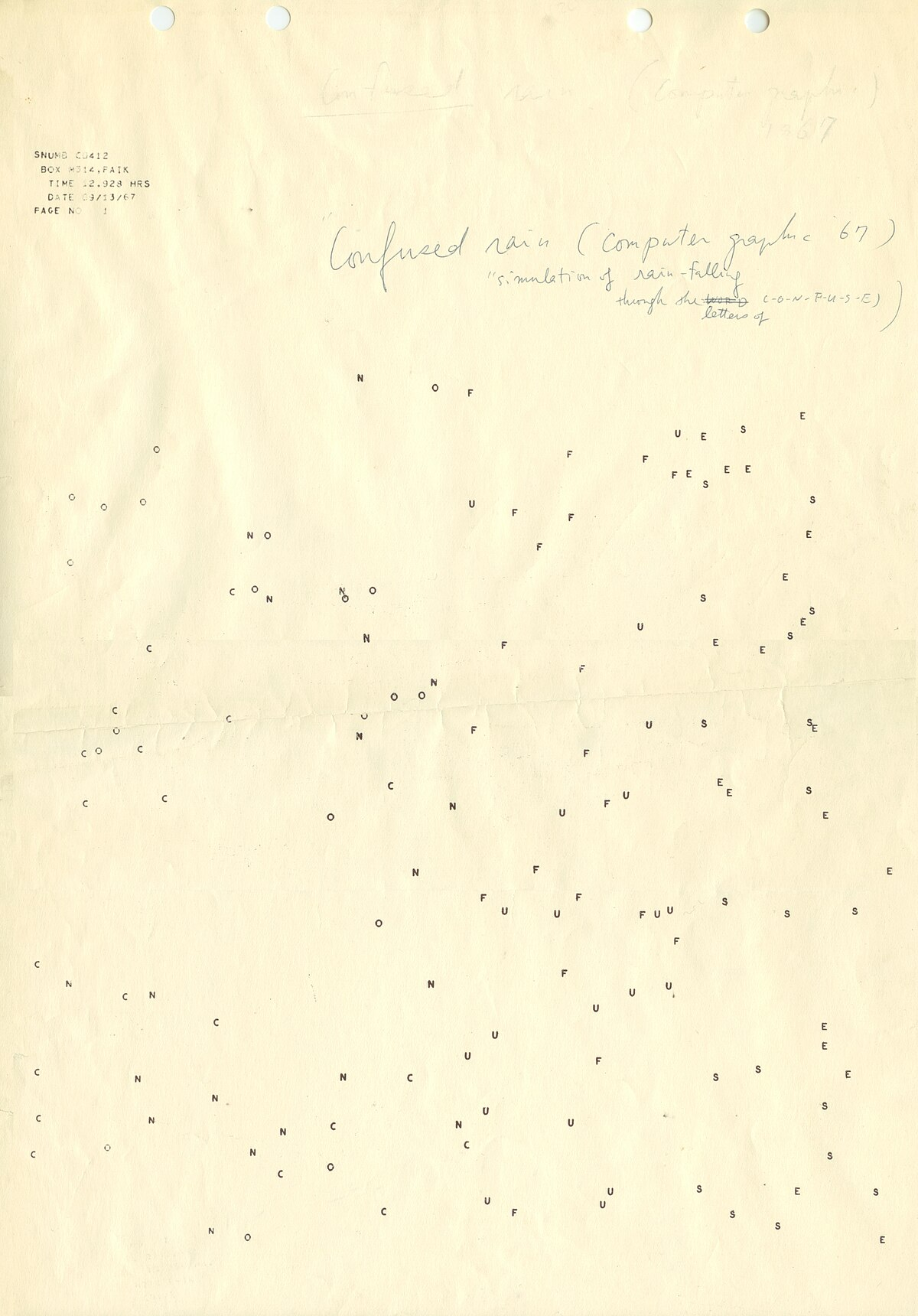

Confused Rain (1967) - a printout of the letters confuse falling down a page in a random accumulation, said to be a protest against the lack of common sense of a computer.

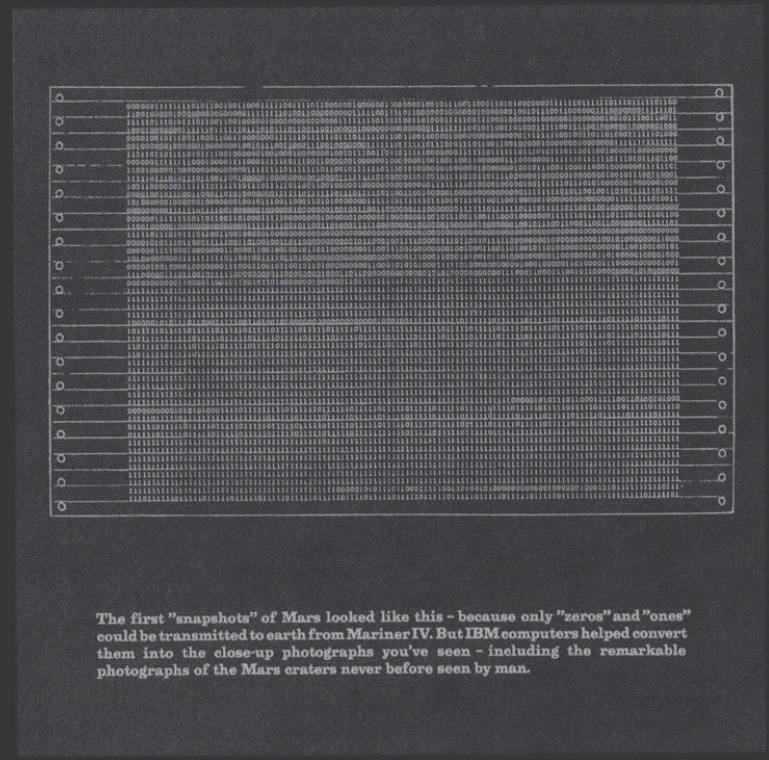

Snapshots of Mars:

Snapshots of Mars:

consists of a page of zeros and ones from print- outs sent back to Earth by Mariner IV of the surface of Mars. These were the first images from a planet long hoped to harbor extraterrestrial life. The decoding of these images would reveal a desiccated surface utterly devoid of life.

Paik presents a section of their binary code.

First-Generation Poetry Generators

Early works of text generation used permutations, transforming ordered lists of base texts into another form.

Dada poets strongly influenced computer poetry. Tristan Tzara’s To Make a Dadaist Poem challenged individuals to make a poem by cutting up a newspaper and then the random selection and reorganization of the articles.

The Role of the Machine in the Experiment of Egoless Poetry

On Jackson Mac Low.

A main theme running through Jackson’s poetry and other creative work is his attempt to develop the Buddhist idea/ideal of egoless expression—that is, to write egoless poetry, theater, or dance.

Diastic poems (greek dia through, stitchos for a line of writing, verse).

The Force between Molecules (each first letter forms the title itself)

The tension between creative work and technical possibility has always existed, from the invention of the first pigments suitable for drawing on cave walls to the use of modern supercomputers for generating film and video images. Different fields of creative work have placed the balance between intuitive creative work and technical development in very different places, though.