created 2025-06-27, & modified, =this.modified

Algorithmic Complexity, also called Kolmogorov Complexity motivates the use of techniques to approximate the complexity of objects and measure the similarity between them. This paper explores the application of these methods to patterns in textiles.

Turing machines can be simulated by knitting. Approximations of algorithmic complexity indicate that there may be a way to distinguish meaningful information from arbitrarily populated matrices. The Turkmen tribes were nomadic people with a social structure that allowed woven ornaments to change independently of one another over time.

Introduction

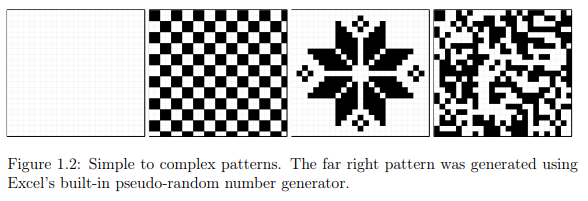

Given an grid where each cell can take on one of two colors there are ways of coloring the grid.

There are similar motifs amongst abstract patterns, such as triangles along with symmetry and repetition. They are easily expressed in small programs.

Thought

There is a notion expressed about “ a range of complexity” of the patterns, where there is an “appealing sweet spot between blank space and noise-type chaos” that resembles Computational Aesthetics

The Mysteries of the Turkmen and their Textiles

In carpet ornaments, in combinations of colors, that have come to us over the threshold of centuries and millennia, there resound different melodic echoes of artistic creativity of the past that have stood firm against the pressure of inexorable all-destroying time. -N. Burdukov, 1904

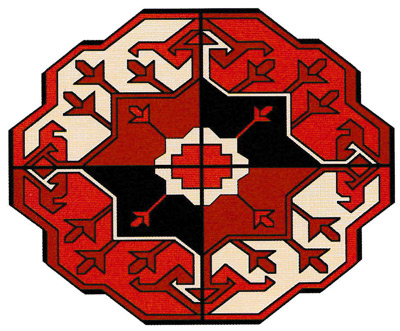

Weaving was a well-established tradition among Turkmen. The rugs covering the floors of the yurts, bags for storage and decorative items were all woven on portable looms. The sheep were sheered in spring and autumn, supplying large quantities of wool.

Weaving was strictly done by women, with skills and designs being passed from mother to daughter. Being a skilled weaver gave her a standing in her tribe. Because patterns were not written or with diagrams small mutations that occurred in patterns would be independent of changes occurring elsewhere. When tribes split, the women carried the patterns with them.

In information theory, one considers problems involving signals transmitted over noisy channels. The repeated transmission of ornaments from mother to daughter over generations is analogous but rather than a noisy channel mutations are introduced through some combination of cognitive bias, subjective preference, and the general propensity of people to doodle.

Knitting and Computability

Where are two patterns the same?

Stitchomorphism – a one-to-one function that preserves the stitches, compound stitches and turns.

Each type of textile has its own language. The language of knitting is a finite alphabet specified in each pattern, where some stitches are composed of other stitches. Two fundamentally different atomic stitches are knit stitches, using k in patterns, and purl, represented by p.

Purl, Knit and Crochet Etymology

The word purl comes from the ancient Scots word pirl, which meant ‘twist’. Crochet is French for “a small hook”. Knit comes from the Old English word ‘cynttan’ meaning to tie in a knot.

Cellular automata Rule 110 is Turing complete, and can be knit, thus knitting can be seen as Turing Complete.

Turing Machine

Example definition used:

a Turing Machine is composed of a finite control, a tape divided into cells, a finite input written on the tape in the finite input alphabet, and those spaces that surround the finite input contain blanks. The tape extends as far as necessary in either direction. A tape head is scanning one of the tape cells. The tape head starts by scanning the leftmost input cell on the tape, then moves, possibly changing states, writing a tape symbol on the cell scanned replacing the current symbol, and moving one cell to the left or right.

Two needles serve as tape heads, called the knit head. Stitches are the counterpart of the tape. Input stitches are a finite number of knit or purled stitches and cast on stitches surround the input stitches (the counterpart of blanks in the Turing tape).

Kolmogorov Complexity

Kolmogorov complexity is uncomputable.

A string’s K(x) is the length of the shortest program that produces it.

Example

010101010101010101010101010101010101010101010101=print 01 24 times

The more complex a string is, the longer the shortest program that produces it will be. The strings with the highest Kolmogorov complexity are called Kolmogorov random strings. There is no shorter way to produce these strings than to simply list each bit of them. As a result the shortest program that produces one of these strings is the length of the string itself plus some constant, like the number 5 to account for the inclusion of the characters in the word print.

Proof of the existence of incomprehensible strings

There are binary strings of length n. There are binary programs shorter than n. Each program only produces at most one string. Therefore at least one string is incompressible.

Invariance Theorem

Given any descriptive or programming language and a program that produces a string, the language that can produce the string with the shortest program is only off by some constant. The constant does not even depend on the string, only on the programming language.

The proof shows that a translation from one language to another can be expressed by some constant number of characters.

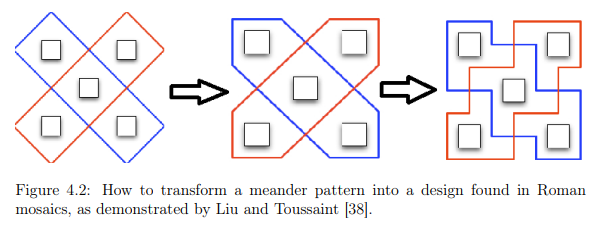

Patterns of one culture can be transformed into another.

Indigenous Circuits L Nakamura

Navajo Women and the Racialization of Early Electronic Manufacture

For Haraway, the women of color workers who create the material circuits and other digital components that allow content to be created are all integrated within the “circuit” of technoculture. Their bodies become part of digital platforms by providing the human labor needed to make them. Really looking at digital media, not only seeing its images but seeing into it, into the histories of its platforms, both machinic and human, is absolutely necessary for us to understand how digital labor is configured today.

References to “nimble fingers” as a digital resource appear in account of how women of color were understood and actively recruited to work in the electronics industry.

The Navajo women actively recruited to work in the electronics of this period are associated with the digital revolution, but rarely figured in. Fairchild Semiconductor produced a racial and cultural argument for recruiting young female workers in the electronics. This was in the period of circuit assembly between 1965 and 1975. Prior to closing it employed 922 Navajos, most women. The reservations acted akin to overseas outsourcing, in that they were not subject to minimum wage laws.

Management’s standard explanation for its preference for young female workers typically rested on the idea that women’s mental and physical characteristics made them peculiarly suited to the intricacies of electrical assembly work.

The plant, which operated twenty-four hours a day, was owned by the Navajo Tribal Council and leased by Fairchild for $6,000 a month. It boasted a very low failure rate—5 percent, in contrast to rates in the twentieth percentile at other plants—and received several awards for its innovative practices.

Navajo leadership pushed the project forward, speaking of the necessity to modernize the tribe.

“It is a brilliant chapter that we write here in the dedication of this magnificent plant. It signals the real and early industrialization of the Navajo reservation. It marks the advancement of the Navajo nation from an Agrarian Nation to an Industrial Nation.”

The work itself was precise and required use of the microscope, and some could not handle it.

For example, after years of rug weaving, Indians were able to visualize complicated patterns and could, therefore, memorize complex integrated circuit designs and make subjective decisions in sorting and quality control.

Fairchild made a brochure in 1969 celebrating the plant and it’s workers.

Inside:

The talents of the Navajo people extend beyond imagination. A Navajo woman weaves a perfectly patterned rug without ever seeing the whole design until the rug is completed. Weaving, like all Navajo arts, is done with unique imagination and craftsmanship, and it has been done that way for centuries.

From 50 initial employees, Fairchild’s Shiprock facility has grown to almost 1200 men and women, making Fairchild the nation’s largest non-government employer of American Indians. All but 24 of the 1200 are Navajo; in fact, of 33 production supervisors, 30 are Navajo.

The blending of innate Navajo skill and Semiconductor’s precision assembly techniques has made the Shiprock plant one of Fairchild’s best facilities-not just in terms of production but in quality as well. Quality becomes a necessity in the semiconductor business. Fairchild’s transistors and integrated circuits, some of which before packaging are no larger than the head of a pin, must perform to perfection in complex computers, electronic appliances, radios and televisions, and on the way to the moon as part of Apollo’s communications, guidance, and gyro systems or in instrumentation units located in various stages of the Saturn rocket. Back on earth, the success of the Shiprock facility can easily be measured in terms of growth and expansion. However, the real value of this progress lies in the creation of meaningful jobs for those who have not had jobs, jobs which will keep them in the land they love and among the people they know. And, that is success in very real terms.

The Navajo men and women working here have made my job as Plant Manager one of the most pleasant experiences of my whole life. Their adaptabilities and proven skills have shown they can do any job well, and their industriousness and desire to learn is unmatched. I hope that in the very near future every job in this plant, including mine, will be held by Navajos. The credit for our success here belongs to them.

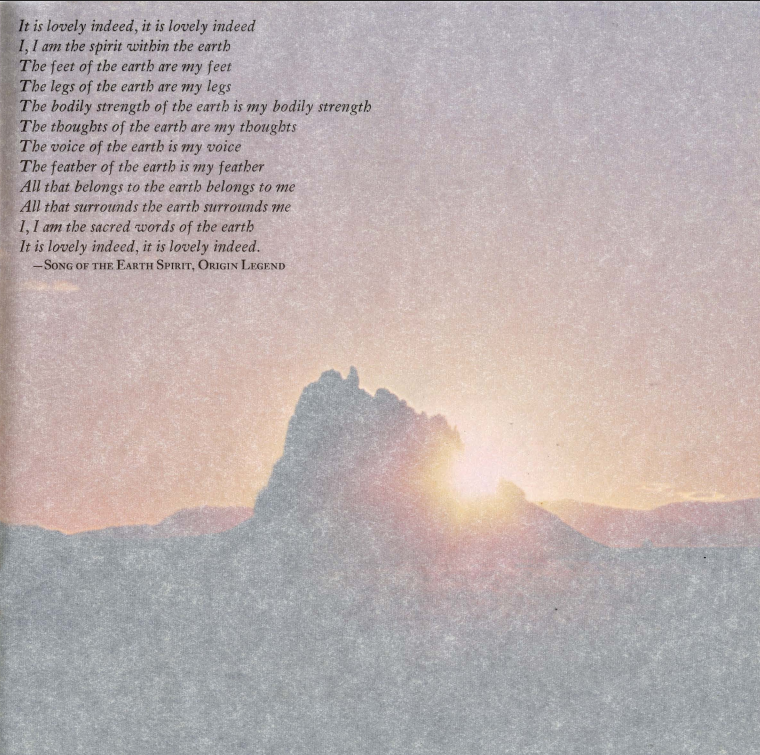

The brochure contains a poem, with the backlit Shiprock mountain (the factory’s namesake)

The appeal to “nature” as a justification for converting “highly skilled” female cultural labor such as weaving rugs into high-tech factory work. The resemblance between the pattern of the rug depicted on the first page and the circuit is striking and uncanny. It makes the visual argument that Indian rugs are merely a different material iteration of the same pattern or aesthetic tradition found within the integrated circuit.

Depicting electronics manufacture as a high-tech version of blanket weaving served two goals

- it permitted the incursion of factories into Indian reservations

- it blurred the lines between wage labor and culturally-creative labor

The argument that Navajo women were good at their assembly jobs because they were good blanket weavers and jewelry makers appears throughout contemporary accounts of the plant.

In positioning them as creative class of workers they are aligned with the personal creative freedom, and are happy because they are creatively fulfilled, not just well paid.

“By the mid-1970s, reports of chemical exposures among production workers had begun to surface” in San Jose, California.31 Given the already high rates of pollution on the reservation from the extraction of resources such as uranium, gas, coal, and oil, semiconductor manufacture continued the ongoing practice of environmental degradation in a spot renowned for its natural beauty. Ultimately, the Navajo nation failed to benefit economically as much as it had expected from the plant and was left to deal with the detritus and its long-term consequences.

Prior beliefs about Indians as unreliable workers unsuited for modern form of labor are transformed into assertions of the positive value of “primitive” habits.

Navajo weaving had a complex cultural identity.

Navajo women did not make circuits because their brains naturally “thought” in patterns of right-angle colors and shapes. They did not make them well because they had inherent Indian virtues such as stoicism, pride in craftswomanship, or an inherent and inborn manual dexterity. And Fairchild did not employ Navajo women because of these traits. These traits were identified after the company learned about the tax incentives available to subsidize the project, the lack of unions and other employment options in the area, and the generous donation of heavy equipment given by the US government gratis as part of an incentive to develop “light industry” as an “occupational education” for Indians

The admin stated future developments would include increased opportunity for Navajo but this never was to be, ad the plant closed and they moved offshore.

Denetdale reads weaving as an important “intellectual tradition,” as does Angela Haas in her essay “Wampum as Hypertext.”