created, $=dv.current().file.ctime & modified, =this.modified tags:computershistorytechnologyscience

Edith Wharton >After a while nothing matters.. any more than these little things, that used to be necessary and important to forgotten people, and now have to be guessed at under a magnifying glass and labeled “Use unknown”.

Astronomy and the Division of Labor 1682-1880 >If your wish is to become really a man of science and not merely a petty experimentalist, I should advise you to apply to every branch of natural philosophy, including Mathematics. >- Mary Shelley

Documenting the return of Halley’s Comet.

The new method of mathematics was calculus, a subject then known in England as fluxions

> Looking into Fluxions, Newton provided a letter to Leibniz with words > > I cannot proceed with the explanations of the fluxions now, I have preferred to conceal it thus: 6accdæ13eff7i3l9n4o4qrr4s8t12vx. > > which contains a hash code, of the Latin phrase Data æqvatione qvotcvnqve flventes qvantitates involvente, flvxiones invenire: et vice versa, meaning: "Given an equation that consists of any number of flowing quantities, to find the fluxions: and vice versa"

In Principia, Newton explained that he was attempting to analyze “the motions of the planets, the comets, the moon, and the sea,” the last term referring to the movements of the tides.

Halley and Newton are followed by Lalande, Nicole-Reine Lepaute and Clairaut. >Clairaut’s computing plan was a step-by-step process that treated Jupiter and Saturn as if they were the hour and minute hands of a giant clock, ticking their way around the Sun.

They worked at a common table in the Palais Luxembourg using goose-quill pens and heavy linen paper. Lalande and Lepaute worked at one side of the table and handed their results to Clairaut. Identifying the source of mistakes was difficult, and even a small error might be compounded in the calculations and ultimately render the final result meaningless.

While they calculated observers awaited the sign of the comet, often falsely detecting its return. To simplify the computation, the presumed minimal influence of Saturn was omitted. The daily routine of computation, the effort to advance the comet eight or ten degrees in its orbit tested their stamina. Lalande said as the result of this work he acquired a lifelong illness. Nicole-Reine carried her share of the burden “without her we’d not dare undertake this work.”

They announced their results, and waited for the return of the comet. Which occurred slightly outside of the interval calculated. “As news of the discrepancy began to spread, astronomers started to assess the calculation and debate its meaning.”

Jean Le Rond d’Alembert, a critic, stated that the calculation was “more laborious than deep”

Clairaut returned to the calculations. There is tremendous temptation to bend the equations in order to fit the data, but he never suggested Newton’s theory required adjustments.

With the perspective on modern astronomy we know that they did not account for the influence of Uranus and Neptune, two large planets that were unknown at the time.

A modern analysis of the result concluded that there were still many problems in the computation and that Clairaut benefited from the “fortuitous cancellation of opposing errors.

Lalande called Lepaute his “assistant without equal,” but of course, she was anything but equal to him. Lalande was able to advance from his position and would eventually be appointed a professor of astronomy and director of the Paris Observatory. Lepaute had no such opportunities…

Stephen Stigler: >No scientific discovery is named after its original discoverer

The Children of Adam Smith > Even in the quieter professions, there is a toil and labour of the mind, if not the body - Jane Austen

Smith claimed that the market encouraged people to specialize, to produce those goods that gained them the most profit. Butchers did not make shoes, nor did cobblers slaughter their own animals. This specialization was one part of a more general idea that Smith identified as the division of labor. “The greatest improvements in the productive powers of labour,” he wrote, “seem to have been the effects of the division of labour.”

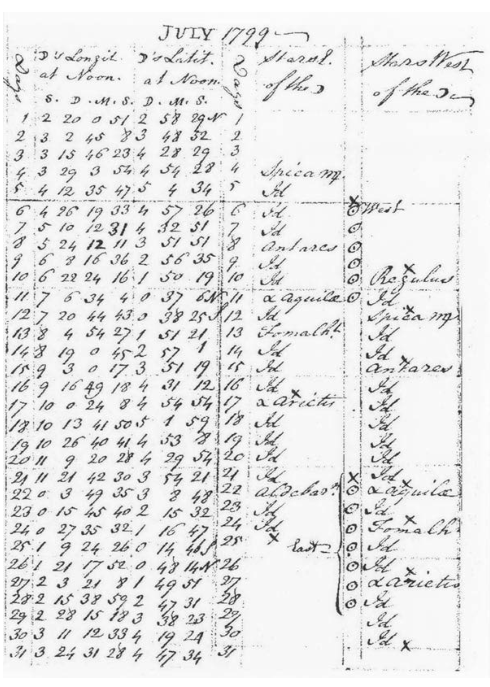

Longitudinal calculations required a single point: the means of determining the time in Greenwich, which allowed a navigator to compare two observations of a single star, one at dawn or dusk and the other as it would be viewed at the identical moment at the observatory in Greenwich.

There were two possible ways of determining the time in Greenwich. A mechanical clock onboard, which was simple but could succumb to shipboard conditions (waves disrupted pendulums, heat and humidity caused distension of springs.) Time would drift, even with a four minute error resulting in a deviation of 50 miles. The other way was to use the moon as a timekeeper (the lunar distance method.)moon For this a table of lunar positions was used.

On the trial voyage from England to Barbados and back, Maskelyne had required four hours to make a single computation of longitude with the lunar distance method.

three >The computers produced tables that tracked the motion of a planet or the sun, tables that were called ephemerides in the plural (or an ephemeris in the singular). Most of these ephemerides were double-computed, prepared by two independent computers working from the same plan. Each computer would send Maskelyne a version of the ephemeris. Maskelyne would forward the two ephemerides to a third computer, who had the title of comparator. The comparator would search the two ephemerides for discrepancies and correct the mistakes. The only tables that were not double-computed were those of lunar motion. These tables were divided in half. One computer would calculate the moon’s position at noon. The other would compute the position at midnight. The comparator would merge the two tables and make sure that the two sets of calculations were consistent.

> The excitement of this. Tables and performing calculations prior to your journey. Observing the moon, to guide you on earth. >

The effort here was to make an almanac produced by Computers.

Babbage finished his Cambridge studies and was newly married. He applied to be a Greenwich Observatory computer, but his friends told him to take his talents elsewhere. His mathematical training was deeply connected to astronomical problems, but it didn’t make him an expert on stars and planets.

Babbage and Herschel tried to augment the British natural almanac. When combining their results they found numerous discrepancies. >“Finding many discordancies,” Babbage later wrote, “I expressed to my friend the wish that we could calculate by steam.

His design would be based on the division of labor. The difference engine: >Though the idea of the adding machine was one hundred and eighty years old, there was none to be bought or sold. The first commercial machine, which would be produced in France, existed only as a crude prototype

His project was interrupted by his wife’s death, which disrupted his life in a way nothing else could have. The loss “left Babbage a changed man” and “there was an inner emptiness to the man who had only recently seen so much potential in his life.” Babbage left the engine unfinished.

He moved onto the Analytical Engine. >The programming mechanism, which read instructions from a string of punched cards, controlled the order of operations. > >One observer, the daughter of the poet Lord Byron, Ada Lovelace (1815–1852), called the Analytical Engine the “material and mechanical representative of analysis,” a triumph of the division of mathematical labor. The Celestial Factory

Saw the heavens fill with commerce, argosies of magic sails, >Pilots of the purple twilight, dropping down with costly bales. >Locksley Hall, Tennyson

In the time of Halley’s return little developments were made by the Astronomer Royal. Uranus was discovered independently. Maskelyne died and most ship officers had abandoned his method in place of chronometers, high precision clocks.

Airy was set to reform the observatory. He was seen as both despotic (initially requiring 12 hour work shifts, where boys computed tables and forms) and progressive and inventive, bringing new efficiency and strength to the Royal Observatory. He was similar to an industrialist, except measured more in public good than pounds sterling.

Airy on the Difference Engine, which caused Babbage to label him an “unimaginative bureaucrat”: >“I can therefore state without the least hesitation,” he wrote afterwards, “that I believe the machine to be useless, and that the sooner it is abandoned, the better it will be for all parties.”

The American Prime Meridian >The eyes of others have no other data for computing our orbit than our past acts, and we are loath to disappoint them… . >Ralph Waldo Emerson

the most well-known of the first computers for the American Nautical Almanac was the sole woman, Maria Mitchell (1818–1889).

When his daughter told him that she had identified a comet, he encouraged her to notify the observatory. When she resisted the idea, William Mitchell communicated the discovery himself. “Maria discovered a telescopic comet at half past ten on the evening of the first instant,” he wrote. “Pray tell me whether it is one of George’s Airy of the Greenwich Observatory… . Maria’s sup- posed it may be an old story.” The observatory confirmed that the comet was new and initiated an energetic effort to ensure that Maria Mitchell was given credit for the discovery. The object of their effort was King Christian VIII of Denmark. The king awarded a medal to the discoverer of any comet

For about half of the computers, including Maria Mitchell and Sears Cook Walker, Charles Henry Davis distributed detailed computing plans through the mail.

December 1849, she asked for a copy of Theoria Motus Corporum Coelestium in Sectionibus Conicis Solem Ambientium (The Theory of the Motion of the Heavenly Bodies Moving about the Sun in Conic Sections) by the German astronomer Carl Friedrich Gauss (1777–1855). This book, one of the last major astronomical texts written in Latin, had a fairly complete discussion of the techniques of astronomical calculations. “I have directed my bookseller to endeavor to get two copies for the almanac office,” Davis responded, “and will add a third to the list for yourself if you wish it.” He concluded the letter by commenting, “I am glad you read Latin.”

On the Cambridge Almanac office, remote work: >One young computer recalled coming into the Cambridge office on a frosty January morning, taking a “seat between two well-known mathematicians, before a blazing fire.” It was an informal place, where new ideas of mathematics were freely discussed between calculations, as the “discipline of the public service was less rigid in the office at that time than at any government institution I ever heard of.” Each computer was expected to spend five hours a day in the office. “The hours might be selected by himself, and they generally extended from nine until two, the latter being at that time the college and family dinner hour.” All that Davis required was that the work was done on time.

A Carpet for the Computing Room Civil War, Telegraphs and Weather >The Signal Corps created a small computing staff that processed all of the weather data in intensive two-hour shifts. Computers worked at stand-up desk where they recorded the information on preprinted forms and blank weather maps

In the two decades that followed the end of the Civil War, women began to find a place in the computing rooms. Just as their male counterparts were no longer educated gentlemen, these women were not Maria Mitchells or Nicole-Reine Lepautes, the talented daughters of loving fa- thers or the intelligent friends of sympathetic men. They were workers, desk laborers, who were earning their way in this world with their skill at numbers. In many ways, they were similar to the female office work- ers, who were increasingly common in the nation’s cities. Before the war, offices were closed to women, except for those well-nurtured daughters, loyal helpmates, or resilient widows. The war had opened government offices to women, as the federal agencies needed more clerical workers than they could draw from the dwindling pool of male labor. Many of these first female clerks were, in fact, war widows, women who had mar- ried in the first exciting days of the conflict and lost their husbands on some hallowed battlefield in Tennessee or Virginia. These women earned a meager salary from the government that often had to support children and mothers in addition to the worker herself.

>Saunders - >Sorry her lot, who adds not well; >Dull is the mind that checks but vainly; >Sad are the sighs that own the spell >Symboled by frowns that speak too plainly.

Observers worked at night >Happy the hour when sets the sun; >Sweet is the night to earth’s poor daughters, >Who sweetly may sleep when labor is done, >Unlike their brother astronomers.

Sweet sleep as respite from toil, with red ink used to correct mistakes >Heavy the sorrow that bows the head >When fingers are tender and the ink is red

via harvard historical site >The women were not allowed to observe at night or assist observers, as women up late at night alone with men was unseemly. I’m not so sure that the women were happy about this, as it was basically a career ceiling. I’m also not convinced it was completely true. In a journal in 1900, Williamina Fleming mentioned that the women would sometimes look through telescopes in their leisure time after work. Given that many of them would know how to operate the instruments, and the men could use the help, I wonder if there was ever any unofficial work.

Mass Production and New Fields Of Science 1880-1930

Slide rule was mass produced in 1880s but was a 1622 invention by William Oughtred, who used the concept of logarithms

> Special values that converted multiplication to addition. For any number a mathematician could find the corresponding log. For example log 2 is 0.3010 while log 3 is 0.4772. By adding the two we get 0.7782 which is the log of 6, the produce of 2 and 3. > > log(5 x 10) = log(5) + log(10), which is useful where multiplication of large numbers can be computationally intensive.

Punch card tabulation: > In later years, he would claim that he found his inspiration by watching a train conductor punch holes in a ticket.

The card was placed on a little frame, and an array of wires was lowered upon it. If the wire encountered a hole, it would complete a circuit and advance a counter. If it encountered cardboard, it would do nothing.

One who has not had personal experience in handling cards cannot conceive the stimulating effect which they have upon the imagination of the statistical computer. >The worker described the cards as images of living beings “whose life experience is written upon their face in hieroglyphic symbols” > >One human computer claimed that the sounds of the tabulating machine were “the voice of the archangel, which, it is said, will call the dead to life and summon every human soul to face his final doom.”

Darwin’s Cousins Francis Galton was one of Darwin’s cousins, attempting to find a mathematical way of verifying the presence of natural selection.

Florence Ted Weldon, one of the first college-educated human computers. She did the same tasks that her husband handled. The two of them would spend their summers traveling around England and visiting Italy. Typically, they would collect about a thousand specimens, clean the animals, and measure them. Husband and wife shared the calculations, doing in duplicate.

Pearson’s socialism: >Though he was directing the work, he took his turn with more mundane tasks, such as tending plants, measuring specimens and harvesting the seed.

Alice Lee worked with Pearson, with a bachelor’s degree: >If her name appeared on a paper for simply doing arithmetic, then other scientists could conclude that she was nothing more than a computer. She was attempting to establish a reputation in the field of craniometry, the measurement of skulls. Breaking from the Eclipse: Halley’s Comet 1910

Once more the west was retreating, once again the orderly stars were dotting the eastern sky. There is certainly no rest for us on the earth. - E.M. Forster, Howards End.

Twain’s protagonist could not believe that anyone or anything could have created the stars because “it would have took too long to make so many,” but he conceded that they might have been laid, like the eggs of a frog.

In her mind mathematics were directly opposed to literature. She would not have cared to confess how infinitely she preferred the exactitude, the star-like impersonality, of figures to the confusion, agitation and vagueness of the finest prose - Virginia Woolf Virginia Woolf Night and Day

“With an unknown author,” wrote Comrie, “it is desirable to check considerable parts of the tables, to see if he has the reliability of Andoyer and Peters, the proneness to error of Stein- hauser, Gifford and Hayashi, or the plagiaristic tendencies of Duffield, Benson and Ives.”37 These other human computers had been the targets of pointed reviews by Comrie; and Davis was to join their number. Com-rie worked through the book, table by table and value by value. By re-computing 2,000 entries, he reconstructed Davis’s original computing plan, uncovered a substantial number of errors in the book, and identi-fied the source of each mistake. Comrie noted that the pattern of errors indicated that the computers had verified their results by repeating the calculations a second time, “the poorest possible check” in his eyes. They had made mistakes in rounding the numbers and had introduced errors when they transcribed the values. Even the design of the book did not escape his attention. “The general lay-out of the tables,” Comrie wrote, “shows a lack of acquaintance with many elementary principles of tabulation, lack of consistency and lack of consideration for the user.” The re-view was not entirely negative, though its conclusion, that “table-lovers are assured that they should possess this work,” seemed faint praise

Scientific relief

Thought > Concept of error free tables. Trust in a table.

The Mathematical Tables Project

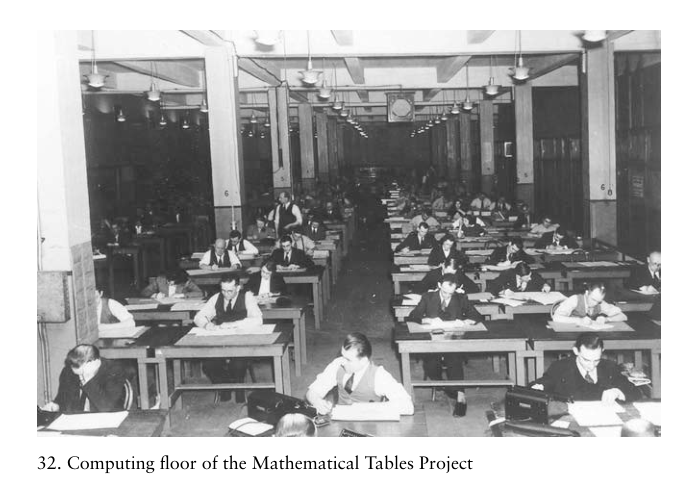

Blanch divided the computing floor into four groups, one for each arithmetical operation. The largest group, did addition only. The elite group was also the tiniest and did long division.

The were isolated, facing a wall with a poster which reminded them, of the operations. Black pencils recorded positive quantities, and red negative.

black plus black is black. >red plus red is red. >black plus red or red plus black, hand the sheets to group 2.

One poorly done table could ruin their reputation.

Individual computers, if cheating (submitting falsified worksheets), would be fired immediately.

Thought > A digital computer whose operation is handled, with the mechanisms inside having their own motives. The bits are deceitful and "lazy." >

Finishing the first table was a relief to the group and created what Blanch called a sense of “heartwarming camaraderie” among the staff.

Tools of the Trade: Machinery 1937

During the great depression, most computing laboratories had at least one staff member with enough mechanical expertise to repair or modify their desk calculators.

Atanasoff on the basic principles of his new machine coming in a late-night epiphany. Late in the year 1937 he had outlined his objectives but nothing was happening and he despaired. Instead of working at his desk, he got into his car and started driving over the good highways of Iowa at a high rate of speed. He stopped at a roadside bar, and relaxed by the drive and drink he identified the key elements for a computing machine that would solve least squares and simultaneous equation problems. It would use a binary number system so the arithmetic could be handled by electrical circuits.

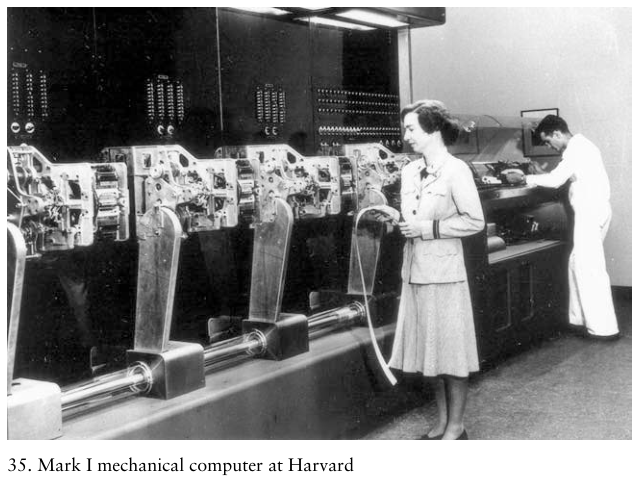

Viewing the new computing machines, Stibitz prophesized that “Human agents will soon be referred to as ‘operators’ to distinguish them from ‘computers”

I am asked to think out an abstract problem when I am very tired out with a multitude of infinitesimal concrete and immediate problems - Anne Morrow Lindbergh

Victor’s Share

Sometime in 1944, computers became “girls.” The University of Penn- sylvania hired “girl computers”; Warren Weaver started calling Applied Mathematics Panel computers “girls”; Oswald Veblen, who had once led a team of computing men, used the term “girls”; George Stibitz began ranking calculating projects in “girl-years” of effort.1 One member of the Applied Mathematics Panel defined the unit “kilogirl,” a term that presumably referred to a thousand hours of computing labor, though in at least one letter it suggested an Amazonian team of computers.2 L. J. Comrie, in an article entitled “Careers for Girls,” stated that girls “can be made proficient and give good service (as scientific computers) in the year before they (or many of them) graduate to married life and be- come experts with the housekeeping accounts.”3 Even at this date, com- puting was not the sole domain of women. It was really the job of the dis- possessed, the opportunity granted to those who lacked the financial or societal standing to pursue a scientific career. Women probably consti- tuted the largest number of computers, but they were joined by African Americans, Jews, the Irish, the handicapped, and the merely poor. The Mathematical Tables Project employed several polio victims as comput- ers, while the Langley research center kept an office of twelve African American computers carefully segregated from the rest of the staff.

The Mathematical Tables Project was one of the largest and most sophisticated computing organizations that operated prior to the invention of the digital electronic computer. It employed 450 unemployed clerks to tabulate higher mathematical functions, such as exponential functions, logarithms, and trigonometric functions.

Gertrude Blanch established MTP - Blanch’s duties entailed designing algorithms that were executed by teams of human computers under her direction. Many of these computers possessed only rudimentary mathematical skills, but the algorithms and error checking in the Mathematical Tables Project were sufficiently well designed that their output defined the standard for transcendental function solutions for decades.

Halley’s Comment returned

The program was written in a language called FORTRAN IV, which was then popular among scientists and engineers. Programming was more exacting than planning, as electronic computers were less for- giving than their human counterparts. Unlike a good human computer, who could correct errors on computing sheets, an electronic computer would follow the instructions blindly, executing each operation even if the action made no sense.

It seems likely that the scientists of the 2061 return of Halley’s comet will shrink Yeomans’s discrepancy to a few seconds, as they will have detailed observations of the comet through its entire orbit and computing tools beyond what we can now imagine.8 It seems equally likely that those same scientists will know little of the daily lives of the computational workers who are so common in our age, the computer programmers, the network managers, and the Web designers. The generation of 2061 may be surprised when an elder of our time explains that she once worked with electronic computers, that she took pride in her skill, that she had been pleased to be part of a scientific endeavor, and that she had once opened a book and studied a subject called calculus.