created 2025-02-27, & modified, =this.modified

rel: Survey of Being Lost

Why I am reading

Walking is an important practice for me. I saw there was a class on “walking as an artistic practice” and that this book had been published in relation to it.

The early prehistoric predecessors of artistic walking are the wandering hunts of the paleolithic period.

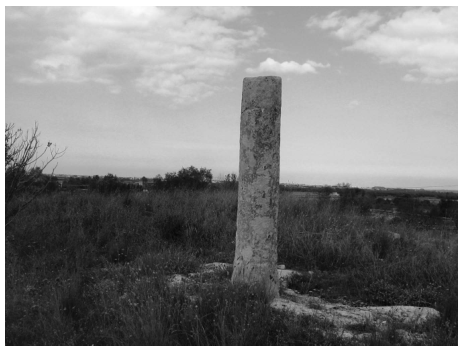

Large-scale stone path markers and their variants, sometimes called menhirs, erected in the Neolithic landscape. The menhirs have widely-debated possible purposes connected to walking, such as “sacred paths, initiations, processions, games, contests, dances, theatrical and musical performances.”

Similarly debated in terms of their purpose, ancient labyrinths are also large-scale walking-related built structures in the landscape. rel:Mazes and Labyrinths - Their History and Development by Matthews

Aristotle is an early example of walking based thinking. In the Peripatetic school in Athens students would walk as they held their discussions.

Bashō suggests that “every day is a journey, and the journey itself home.”

Jean-Jacques Rousseau wrote Reveries of the Solitary Walker which was published shortly after his death. It consists of 10 chapters called “walks” inspired by walks on the outskirts of Paris. He says “To travel on foot is to travel in the fashion of Thales, Plato, and Pythagoras. I find it hard to understand how a philosopher can bring himself to travel in any other way.”

George Santayana - “The roots of vegetables (which Aristotle says are their mouths) attach them fatally to the ground, and they are condemned like leeches to suck up whatever sustenance may flow to them at the particular spot where they happen to be stuck. Close by, perhaps, there may be a richer soil or a more sheltered or sunnier nook but they cannot migrate, nor have even the eyes or imagination by which to picture the enviable neighboring lot.”

Dada

On April 14, 1921, a group of Dada participants met to go on a mock guided tour at Saint-Julien-le-Pauvre churchyard in Paris, a space organizers deemed to have no reason to exist. Andre Breton read a manifesto and George Ribemont-Dessaignes read arbitrary definitions from a dictionary as keys to monuments in the churchyard. This event was meant to reject art’s assigned urban spaces by engaging with a space that was considered banal (the street), and establishing the walk as art, or anti-art.

Surrealism used the term deambulation or errance to describe this newly defined disorientation via purposeless undirected wandering. The goal was to unleash the collective unconscious while walking as a small private group, with emphasis on unplanned chance encounters. After returning from one of these walks, Breton wrote one of the first Surrealist manifestos.

Situationists wanted art without artists or artworks and were fans of the ephemeral. There was support for rejecting representational art and the concept of personal talent, and instead favored the directly lived moment. In other ways, the Situationists succeeded by innovating with new forms of walking and critically thinking about everyday urban spaces by emotionally disorienting oneself.

Situationist, Marxist group leader Guy Debord published information about dérive (some also used the term drifting) describing walking a scientific experiment or tool in urban walking, as opposed to a chance-based operation.

Michèle Bernstein who was an avid drifter, who claimed the dérive “wasn’t a hobby, Situationist wanted to make it a way of life.”

The dérive is a small-group walking exercise, and through this joint experience, the Situationists wanted pedestrians to become more aware of their overlooked urban surroundings and begin to see new possibilities.

Psychogeography

From the Letterist International and Situationist International, is the exploration of urban environments that emphasizes interpersonal connections to places and arbitrary routes.

Please, walk on here (Kono ue o aruite kudasai) (1955) by Shozo Shimamoto (1928–2013), which consists of a bridge-like structure on the ground. Participants were asked to walk on the structure and sense the structure’s instability or imminent collapse as they are walking.

In contrast, Roberley Bell’s (1955–) Still Visible After Gezi (2015) centers photography as the work itself. The photos capture trees the artist encountered on walks through Istanbul in 2010, and then tried to revisit in 2015 after the 2013 Gezi Park protests. In this case, the carefully selected photos are arranged into specific groupings that describe the trees, or their absence, making the photographic arrangements into the work itself, rather than a document of live work that occurred in the past. This use of the photo helps emphasize the importance of the memories, as well as their ephemeral nature.

Gao Qipei (1660–1734), known for painting landscapes, animals, and people using his fingers and nails rather than a brush.

The mid-1800s concept of the flâneur/flâneuse was simply a person (most often an upper class man at this time) who strolled the city in order to experience it as a passive observer with a disengaged point of view.

Similarly, the mid-1900s concept of the dérive, or drift, was a playful technique for wandering rapidly through cities, not for commuting or leisure, but to experience the attractions or repulsions of the topography, architecture, and the atmosphere of a place.

On Kawara (1933–2014) traced all his movements on maps for twelve years in a piece entitled I WENT (created 1968–1979, published 2007). There were twelve books of these maps with 4740 pages total. Each daily trip is traced in a red line on a map and is dated. When taken collectively, the books convey the enormity of the passage of time and the breadth of physical distances—issues often overlooked when considering ordinary activities.

Leading versus Following

Vito Acconci’s “Following Piece” which consisted of him leaving his apartment every day for 23 days to follow random people on the street till they entered a cab, residence or other private place. Along with taking photographs and written notes, he typed up descriptions of these acts of following and sent them to arts professionals. Some interpret this piece as an exploration of public versus private space, while others point out the problematic power dynamics and similarities to stalking, due to the lack of consent.

Yoko Ono and John Lennon (1940–1980) similarly made a video work in 1969 entitled Rape, in which a young walking woman was fol- lowed without consent to create a seventy-seven-minute film. While Ono and Lennon intended the work as a commentary on the lack of privacy celebrities endure, it is an ethically problematic work because the woman who was filmed was not allowed to opt out of the following experience, thus perpetuating the very concept it was intending to critique.

In The Shadow (1981), Sophie Calle requests her mother hire a detective to follow her and photograph her without her knowledge (the detective did not know that Calle knew he was following her). While Calle initiated this project, and clearly provided consent, the project still examines the ideas of watching and being watched without knowing when and where it’s happening. She later exhibited the photographs and descriptions, continuing to ask questions about public and private control, as well as voyeurism, exhibitionism, and chance.

In Museum Highlights: A Gallery Talk Andrea Fraser gave a tour of the Philadelphia Museum of Art assuming the role of a fictional docent who lead conventional analysis of the art but also tours of the toilers, cloakroom and gift shop, drawing attention to the exaggerated praise and prescriptive aesthetic values docents in tours can sometimes employ. Walking, in this satire, is a social critique.

Artist’s Absence

The leader not be physically present. For example, maps, score, archives can lead a participant.

Street with a View (2008) by Ben Kinsley (1972–) and Robin Hewlett (1980–). This work was a collaborative effort between the artists and the Google Street View team in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. The artists staged humorous action scenes along routes where the Google team was updating photographs for Google Maps with their 360-degree cameras. These entertaining tableaux photographs lived as an archive on Google Street view for a period of time until the street views were updated. Users of Google Maps could follow these artist-crafted views on a self-led walk. The humorous images were counter to the usual photographs on Google Maps, which are normally simply informative.

Who gets to walk and where?

The streets are free and belong to everyone. The pavement is one of the few opportunities for casual, embodied encounters with difference.

Kinder Mass Trespass - In 1932 over 400 people trespassed onto Kinder Scout, a moorland plateau in England where a small group of wealthy people wanted exclusive use for hunting. The trespassers wanted to highlight how the public was denied access to areas of open country. The action helped contribute to the creation of English National Parks in 1949, the development of long-distance footpaths across England, and the Countryside and Rights of Way (CROW) Act in 2000 securing walker’s rights over open country and common land.

Stuart McAdam’s Lines Lost. Walked the abandoned routes of Scottish railroad lines that were eliminated. Once again highlight the conflict between private land and the right to roam.

Armor (2015) by Kubra Khademi, which is an eight-minute walk by Khademi down a busy street in central Kabul, Afghanistan, wearing custom-made armor that emphasized her breasts, stomach, and buttocks.

Rituals

I have walked myself into my best thoughts. - Søren Kierkegaard

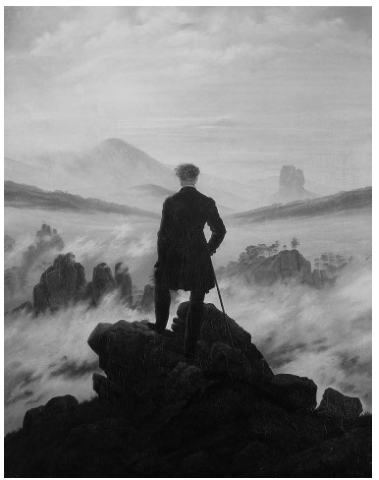

Caspar David Friedrich’s Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog

Narcotourism (1996) by Francis Alÿs (1959–) is a walking work that examines contemplation, but over a shorter period of time—seven days—and each day under the influence of a different drug.

Gardens

Walking in nature holds a certain appeal across history and cultures. In some cases, the practice has been formalized, as in Japanese forest bathing (shinrin-yoku), “the practice of absorptive, enveloping walking in deep forests for the soothing properties of being connected to, and fully immersed in, the sights, sounds and feel of nature.”

Labyrinths are single path to center, unicursal model. Mazes are multicursal and contain dead ends, branching paths and a lack of center, promoting a sense of confusion through their complexity.

Walking for pilgrimages. Walking for laboring and tests of character.

Wandering

Art historian Lexi Lee Sullivan (1982–) points out that in ancient Greece, there were nomadic Cynics who searched for truth outside of the norms of society, meaning they gave up their possessions and resisted the status quo, using walking as a countercultural activity.

Place

Artist Mary Mattingly (1978–) reflects on the definition of home in her multifaceted project House and Universe (2011–2013), in which she bundled most of her possessions into a series of boulder-sized collec- tions. She photographed them and displayed them in galleries, and also pulled them through the streets of New York City in sub-project Pull (2013), as an absurd walking performance to emphasize the weight of the objects, both in her life, and as an eventual contribution to a landfill. The exchanges and memories associated with each possession contribute to an understanding of home, and their physical weight on the walk makes visible the emotional importance of one’s home.

Another example of exploring the local is Long Trace of Minneapolis (2016–2018) by Larsen Husby (1990–), which involved walking every street in Minneapolis, a total of 1,315 miles, through this city of 422,331 people. Husby set up guidelines for himself that involved walking the entire length of each street, as legally allowed, and recording each route. Through the walking, Husby noted chance encounters with other pedestrians when they were present, changes in architecture and landscape, and the car-centric nature of the city. This exercise was in part an effort to get to know his local city better, and this literal trace of the street grid was his means of reflection.

Artist Amy Sharrocks has written and presented on this topic, and identified five phases to any fall: approach, letting go, falling (out of control), crash, and recovery.

Types of Walking (to Inspire)

rel: Words

- Ambling

- Arriving

- Breaching

- Bushwhacking

- Crossing

- Dérive / Drifting

- Descending

- Flânerie

- Following

- Geocaching

- GPS drawing walks

- Group walks

- Guided walks

- Haunting (as in Virginia Woolf’s “street haunting”)

- Hiking

- Hopping on one foot

- Investigating

- Jaunting

- Journeying

- Leading

- Leaving

- Meandering

- Migrating

- Moon walking

- Mythogeography (as in Phil Smith’s book, Mythogeography: A guide to

- walking sideways)

- Navigating

- Nomadism

- Orienteering

- Parkour

- Pilgrimage

- Perambulating

- Procession

- Promenading

- Protests

- Psychogeography

- Pub crawling

- Questing

- Rambling

- Retracing your steps

- Roaming

- Rolling

- Sauntering

- Scored walks (following directions)

- Sensory walks

- Shuffling

- Skipping

- Sleepwalking

- Smellwalking

- Solo walking

- Spacewalking

- Speed walking

- Stamping

- Stilt walking

- Stomping

- Strolling

- Tailing

- Three-legged walking

- Tightrope walking

- Tiptoeing

- Tracing

- Tracking

- Trailing

- Tramping

- Traversing

- Treading

- Trekking

- Troubadouring

- Visiting

- Walking for mental health

- Walking for physical health

- Wandering

- Wayfaring