created, $=dv.current().file.ctime & modified, =this.modified

tags:computershistoryaiautomata

Albert the Great’s automaton

The reason Naudé cited was the statues’ lack of equipment: being altogether without “muscles, lungs, epiglottis, and all that is necessary for a perfect articulation of the voice”, they simply did not have the necessary “parts and instruments” to speak reasonably

Instead, Albert’s machine must have been similar to the Egyptian Statue of Memnon, much discussed by ancient authors, which murmured agreeably when the sun shone upon it: the heat caused the air inside the statue to “rarefy” so that it was forced out through little pipes, making a murmuring sound

Egyptian

In 27 BCE, a large earthquake reportedly shattered the northern colossus, collapsing it from the waist up and cracking the lower half. Following its rupture, the remaining lower half of this statue was then reputed to “sing” on various occasions – always within an hour or two of sunrise, usually right at dawn.

Described as a blow, the string of a lyre breaking, whistling, or the striking of brass.

Appears to have blended with myth, as hearing the sound was said to confer luck.

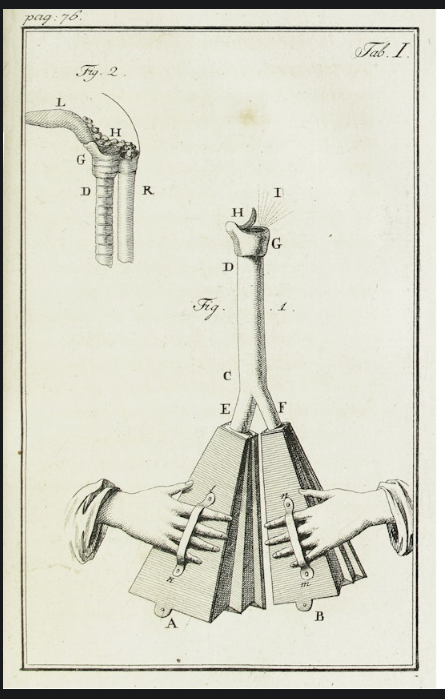

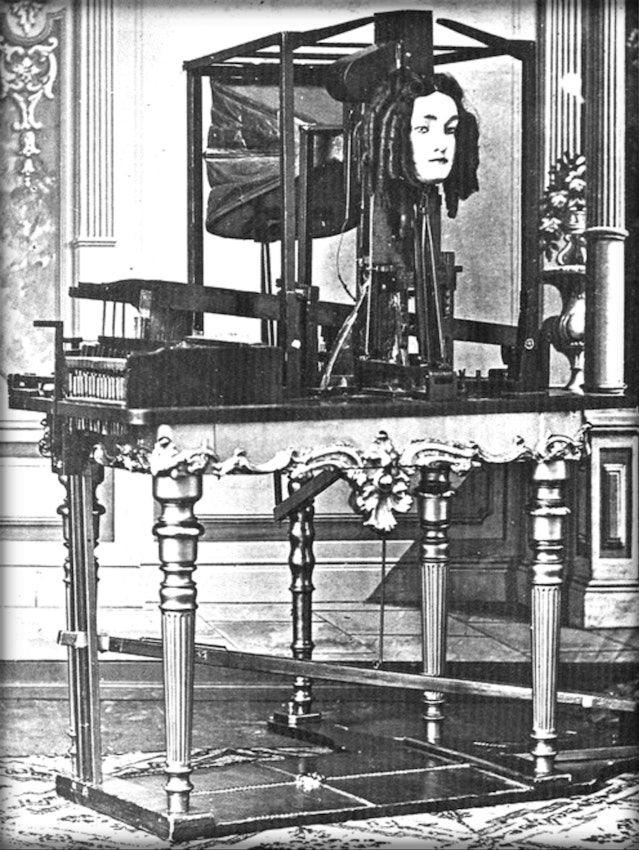

Jacques Vaucanson’s flue playing android.

The abbé Pierre Desfontaines, a journalist and popular writer, advertising Vaucanson’s show to readers of his literary journal, described the insides of the Flutist as containing “an infinity of wires and steel chains … which form the movement of the fingers, in the same way as in living man, by the dilation and contraction of the muscles. It is doubtless the knowledge of the anatomy of man … that guided the author in his mechanics

The android musicians did not just make music, a feat that music boxes had achieved for more than two centuries, but they did so using flexible lips, moving tongues, soft fingers, and swelling lungs. They were simulations of the human process of making music, and as the century wore on, the designers of such simulations turned toward the even more complex task of making machines that could mimic human speech.

In 1648, John Wilkins, the first secretary of the Royal Society of London, had described plans for a speaking statue that would synthesize, rather than simulate, speech by making use of “inarticulate sounds”. He wrote, “We may note the trembling of water to be like the letter L, the quenching of hot things to the letter Z, the sound of strings, to the letter Ng , the jirking of a switch to the letter Q, etc