created 2025-06-14, & modified, =this.modified

rel: Musical, Sound Architecture Bodega Music Experiment

Why I’m reading

I grew up and accepted music as part of shopping, and elevators. Reading for Musical, Sound Architecture I noticed the pipe organs being placed in department stores, which I didn’t realize expect.

I’m curious too about this “background” music. People listen to music while they work. I’m imagine with certain tracks you could listen to them the whole day, and not even recall one.

It masks uncomfortable silences, and provides stimulation. What are the consequences?

I’m also somewhat nostalgic about these sounds. I’ve tuned into the archive of K-Mart in Attention K-Mart Shopper in a manner completely divorced from shopping.

This format, is also an easy target for deep learning based replicas (for amongst many reasons, no need to pay for music rights.)

General Muzak History

To be elaborated in the text, but as a summary.

General George Owen Squier invented and popularized Muzak.

He was responsible for telephone carrier multiplexing and In 1922, he created Wired Radio, a service which piped music to businesses and subscribers over wires. In 1934, he changed the service’s name to ‘Muzak’.

This allowed music to be broadcast without the use of radio, using wires like powerlines. Later when tied with consumer environments, it became the background music of capitalistic America, deliberately non-aggressive and paired down.

A note on Brian Eno’s Music for Airports

“Whereas [canned music’s] intention is to ‘brighten’ the environment by adding stimulus to it,” Eno wrote in the liner notes of Music For Airports, “Ambient Music is intended to induce calm and a space to think.” As opposed to Muzak, which Eno thought forced the listener into a certain mode of behaviour, he said, “Ambient Music must be able to accommodate many levels of listening attention without enforcing one in particular; it must be as ignorable as it is interesting.”

Probing the Jell-O

As restaurants, elevators, malls, supermarkets, office complexes, airports, lobbies, hotels, and theme parks proliferate, the back- ground, mood, or easy-listening music needed to fill these spaces becomes more and more a staple in our social diet.

Judgments levied, “boring, dehumanized, vapid, cheesy – elevator music”

American Symphony League insists host personnel turn of Muzak in hotels where it holds conventions. “We want to be sensitized to music, not desensitized to music.”

Andy Warhol went further by being among the very few celebrities with a public endorsement: “T like anything on Muzak—it’s so listenable. They should have it on MTV.”

Muzak is a registered trademark, like Kleenex or Xerox.

Gary Gumpert:

“Muzak is music that is put in a laundromat. It’s been bathed; and all of its passion gotten rid of. It’s there; it doesn’t make a wave. It’s just a kind of amniotic fluid that surrounds us; and it never startles us, it is never too loud, it is never too silent; it’s always there…”

Lullabies from Heaven and Hell - Mood Music’s Antiquity

The soothing nature of music: Orpheus played his lyre to inspire Jason and the Argonauts on their quest for the Golden Fleece, and the melodies also blocked out the chorus of the sirens.

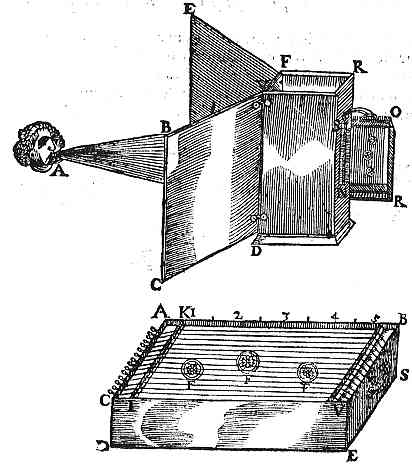

Self-generating Aeolian harp (named after Aeolis the god of winds) consisted of a box with strings pulled across its openings to make celestial noises on windy days.

It was intended to be played not by human hands, but by the God of Wind himself. Its melodies and harmonies were not those chosen by humans, but were held to be the improvisations of Nature itself.

Germany’s Robert Schumann was at first content to believe that singing angels were visiting him, but he suddenly had a nervous breakdown after concluding that the choirs were “those of demons and in hideous music.”

Florence Nightingale in Notes on Nursing: “wind instruments capable of continuous sound have generally a beneficial effect on the sick, while the pianoforte with such instrument as have no continuity with sound has just the reverse, the pianoforte while playing will damage the sick, with an air like “Home Sweet Home”… on the most ordinary grinding organ with sensibly sooth them…”

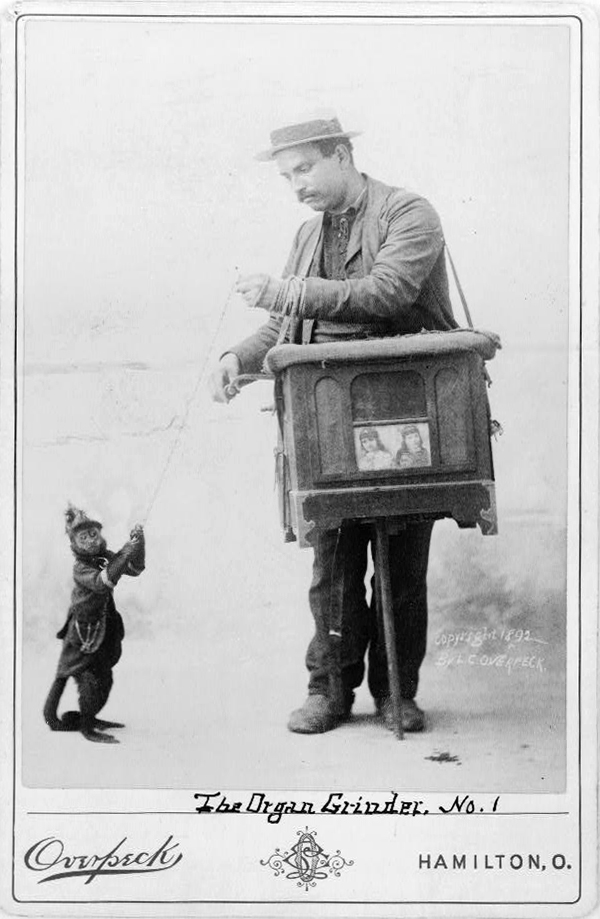

Grinding Organ

The street organ, played by an Organ Grinder – French automatic mechanical pneumatic organ designed for mobile play.

I’m wondering if there is an analogy here to the sense of “roaming” music you hear on the subway or around town – fragments of songs as people pass by, perform or blast their own “nuisance” tracks. A more accurate comparison might be the Times Square costumed characters.

George Orwell wrote of the organ-grinders of London: “To ask outright for money is a crime, yet it is perfectly legal to annoy one’s fellow citizens by pretending to entertain them. Their dreadful music is the result of a purely mechanical gesture, and is only intended to keep them on the right side of the law.

Fucking hell -

In New York City, the massive influx of Italian immigrants led to a situation where, by 1880, nearly one in 20 Italian men in certain areas were organ grinders.

Hundreds of organs were destroyed, as they were considered a public nuisance in NYC in 1935. This lead to the loss of music, as this was the only permanent recording of these tunes.

The barrels used were heavy, held only a limited number of tunes, and could not easily be upgraded to play the latest hits, which greatly limited the musical and practical ability of these instruments.

Schopenhauer predicted movie soundtracks in The World as Will and Idea:

“This deep relation which music has to the true nature of all things also explains the fact that suitable music played to any scene, action, event, or surrounding seems to disclose to us its most secret meaning, and appears as the most accurate and distinct commentary upon it.”

Thought

I’ve been in situations where I should be expected to feel deeply sad, but was unable to bring myself to tears. Then, stopped at a traffic light with a particular song – then I cried.

Mario Morasso

“the holy temple, as a means of satisfying a spiritual need … has become the Department Store or the clerical office. …”

Thought

Yes! This is what I enjoy and wanted to get at. Finding no extraworldly reverence to a “holy temple” I also find it so funny that a department store would come to the call to satisfy the spirit.

Silent became an uncomfortable anomaly after the Industrial Revolution.

Boilermaker’s Disease: The making of boilers during the early days of the Industrial Revolution first produced this affliction among workmen in these factories, and by analogy it has come to refer to any form of industrially-induced hearing loss. Now known as Noise Induced Hearing Loss (NIHL).

Karlheinz Stockhausen later suggested using computer-programmed “sound swallowers” to neutralize every unwanted noise in a public place with its opposite vibration.

Stockhausen Interview

I find mention of this in a QnA

Q: How do you see the dichotomy between noise and sound? Stockhausen: …I became aware that all sounds can make meaningful language. There’s a tribe in Africa, the Xhosa; they make only clicks (imitates sound). So I used these clicks, and I had even to transcribe the language; I didn’t know at all what it meant. Language is already extremely rich concerning all kinds of sounds. We can sneeze, we can bark, we can make or imitate all the sounds in a factory, traffic, animals, etc. And I became aware that this can all become musical material. Already after 22, 23 years I knew that the traditional limitation of musical sounds was finished and that we enter now a new era where everything, all the acoustic world, can be transformed into art. That is the point. So that in the future, when we walk through an airport or a large hall, what we hear is artfully shaped as sound, and not just a mixture of garbage. I’ve even proposed at a certain moment in my life to invent “sound swallowers” so that one could make certain sections in a city silent. There would be microphones everywhere with a computer. One produces the counter-wave of the sounds which are produced. And then, even if you speak, one cannot hear anything. And there should be only areas in a city where you can talk or scream, whatever you like, but in most of the parts there would be no sound, because there would be sound swallowers everywhere.

Mechanical sound reproduction engendered what an unapproving R. Murray Schafer in The Tuning of the World calls “schizophonia,” a state in which contemporary life is “ventriloquized” by noises duplicated, transmitted, and divorced from their “natural” sources.

The Canned Avant-Garde

Luigi Rossolo’s Futurist painting Music (1911)

He appears to be slumped over his keyboard, dwarfed by a leering electronic chorus that keeps him in the dark and plays on, regardless of whether he lives or dies.

Russolo created Intorarumori (Noise Intoners), speaker boxes that transmitted chainsaw melodies as internal combustion engines gurgling in ten whole-tones. He had four main noise families: the exploder, the crackler, the buzzer and the scraper.

Satie coined musique d’ameublement – furniture music (furnishing). Erik Satie was a precursor in imagining the use of music as a sound ambiance in specific everyday situations and places, reduced to an object of consumption.

Something likened to an easy chair.

As an origin, Satie was at restaurant with painter Fernand Léger. The resident orchestra was so loud diners had to leave. Satie said:

You know, there’s a need to create furniture music, that is to say, music that would be a part of the surrounding noises and that would take them into account. I see it as melodious, as masking the clatter of knives and forks without drowning it completely, without imposing itself. It would fill up the awkward silences that occasionally descend on guests. It would spare them the usual banalities. Moreover, it would neutralize the street noises that indiscreetly force themselves into the picture.°

When he first played in 1920, it was no made to attract attention in any way but patrons who were unaccustomed proceeded to strain with their ears. Satie leapt in the crowd and implored everyone to talk, make noise or concentrate on the picture exhibition.

France shifted from a market economy to consumer culture.

Umbilical Chords - Birth of Muzak®

1887 Edward Bellamy’s book Looking Backward envisioning the world of 2000AD.

In one part he wrote: “Please look at today’s music,” she said, handing me a program, “and tell me what you prefer.” It was dated September 12th, 2000, and contained a long list of music. I noticed that selections were grouped under headings 6:00 p.m., 7:00 p.m., etc. Then I observed this program was an all-day affair divided into sections corresponding to the hours of the day. “How is it done?” I asked. “There are a number of studios,” she answered, “adapted to play all kinds of music. They are connected by telephone with hotels, restaurants, and homes throughout the City.” Fifty years ago Mr. Bellamy came very close to prophesying exactly what “Music by Muzak” is today.

Bellamy and Huxley both saw how much would be a disembodied muse but different in that Bellamy saw it with a humanitarian purpose (background chorus) while Huxely lamented the passing of individual rights and the filling of empty spaces with “agreeable languor”.

Muzak = music + Kodak

The Push-Button Ballroom - Mood Music and Early Radio

Radio helped people forget the rigors of the Depression. In 1930 40% of American households had a radio, in eight years it jumped to 82%.

Radio was the “ultimate extension of personality in time and space.”

Average listeners were free to select the music they wanted to match their personality and mood. Kostelanetz, “every one is his own master, and incidentally mater of the program.”

Ghosts in the Elevator

In hotels, office buildings, and many other places, one is perpetually awash in soft music, as in America. Plaintive arias leak from the walls in elevators, waiting rooms, bars, and lavatories; the music comes from nowhere, like a ventriloquist’s voice – Luigi Barzini

Riders of early elevators felt safer when a uniformed attendant was on hand to guide them through their “uncertain vertical passage.” This was superseded by the comfort of elevator music.

When it was known was Wired Radio, Muzak® was transmitted to grocery stores equipped with loudspeakers.

Muzak’s first 1934 recording was a medley of “Whispering,” “Do You Ever Think of Me?” and “Here in My Arms,” performed by Sam Lanin (brother of Lester Lanin) and his orchestra.

Muzak established four networks

- purple network, served restaurants from 10 to 3:30 A.M.

- red network, offered news reports, weather, sports updates and time signals, intended for bars and grills

- blue network, served department stores

- green network, provided transmissions beamed to apartment buildings for private residences

The March 1946 Reader’s Digest reprinted a Forbes article titled “Have You Tried Working to Music?” “music is now being piped into banks, insurance companies, publishing houses and other offices, where brain works find that it lessens tension and keeps everyone in a happier frame of mind.”

Cardinell:

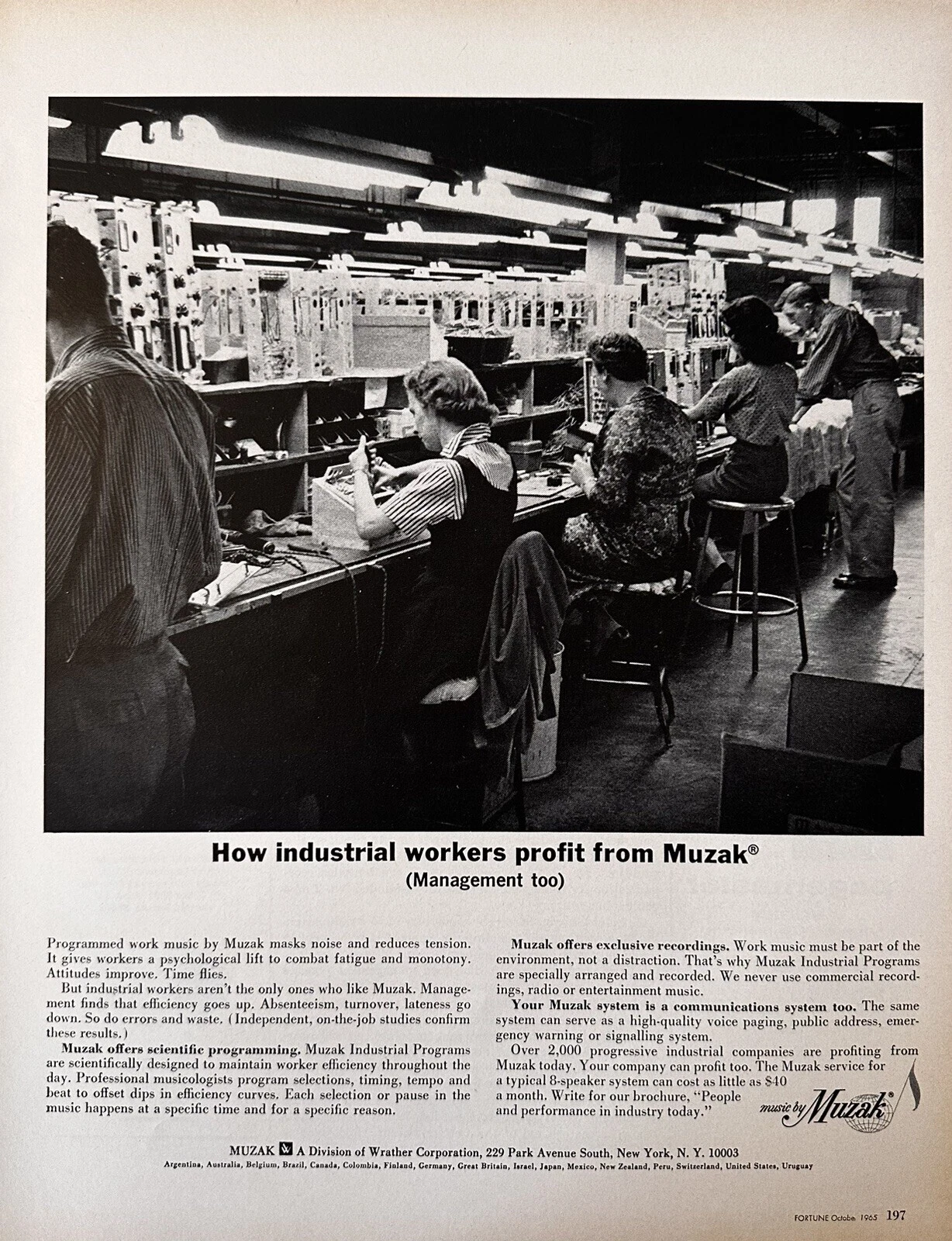

In some cases, it is possible to achieve a direct production increase by playing a program which completely ignores employee preferences and concentrates on the functional aspects only.”

This lead to “Stimulus Progression” by Muzak, a method which organized music according to an “Ascending Curve” that worked counter to the “Industrial Efficiency Curve” that some authorities called the average worker’s fatigue curve. Subdued songs, progressed into more stimulating songs in 15 minute sequences through the workday yielded more worker efficiency than random programming.

Programs were soon tailored to workers’ mood swings and peak periods as measured on a Muzak mood- rating scale ranging from “Gloomy—minus three” to “Ecstatic— plus eight.”

But soon (1950s) the thought arrived that piped in music interferes with the right to privacy and even brainwashes listeners.

But soon (1950s) the thought arrived that piped in music interferes with the right to privacy and even brainwashes listeners.

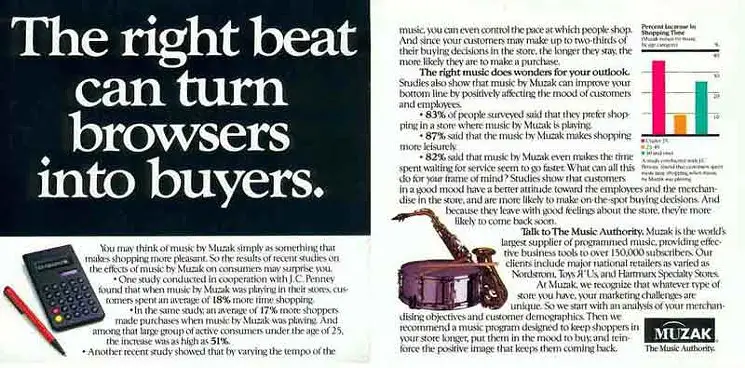

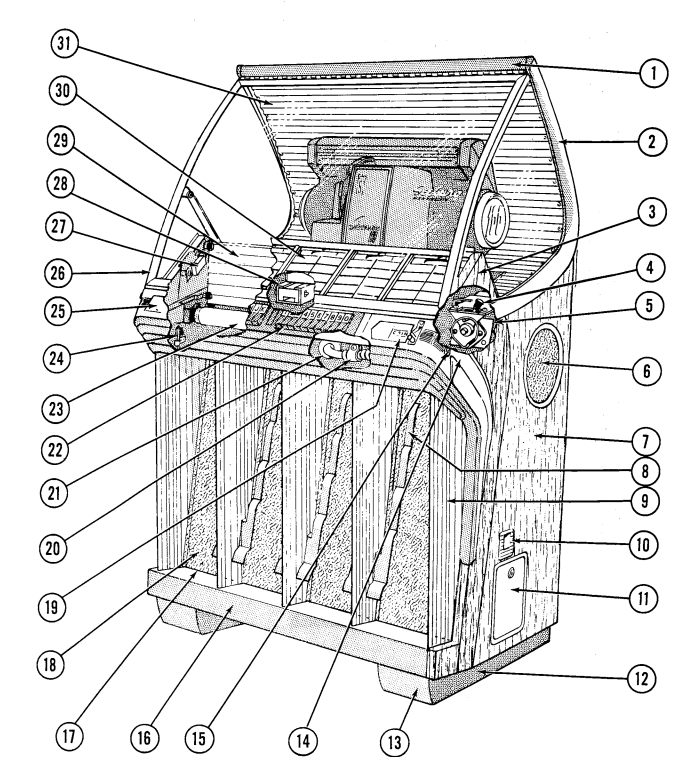

Competition came in the space of background music. Seeburg’s Select-O-Matic.

Seeburg Select-o-matic Jukebox

Looking through a manual online

The Select-O-Matic “100”, Model M100C, is a coin-operated phonograph using the Seeburg Select-O-Matic Mechanism for selective playing of either or both sides of fifty 45 r.p.m., 7-inch records. Choice of any of the one hundred selections may be made at the instrument with an Electrical Selector or by remote control with 100-selection 3-wire Wall-O-Matics. A program holder using standard size title strips displays the entire hundred selection program.

Muzak was installed in the White House during the Eisenhower years.

Background Music in the Movies

Easy-listening music (at least in theory) helps the consumer buy, the patient relax, the worker work; its goal is to render the individual an untroublesome social subject. Film music, participating as it does in a narrative, is more varied in its content and roles; but primary among its goals, nevertheless, is to render the individual an untroublesome viewing subject; less critical, less “awake” – Claudia Gorbman

Thought

The book, Unheard Melodies, this quote is from introduced the concept of diagetic and non-diagetic to describe the relationship between music and film narration.

It’s framed negatively, but I think partially what we are speaking about is music’s ability to guide atmosphere, and immerse. There’s part of me that wants to be critical of the film (“like if the OST was just a track that constantly said BE AWARE”) but also in order to get the full movie experience I have to have some degree of letting go.

By 1934, when people finally got used to music in the talkies, filmmakers began taking full advantage of a device known as “the up-and-downer,” which automatically lowered the music volume when dialogue signals appeared on the soundtrack.

A 1991 cognitive psychology study entitled “Effects of Background Music on the Remembering of Filmed Events” has concluded that movie scenes can be more readily recalled with background music than without. The music seems to provide a setting by which viewers develop better schematic processing through memory cues.

Moodiest Years on Record

Mood Music

Columbia Records released a Quiet Music series of instrumen- tals performed by the Columbia Salon Orchestra that were meant to calm the nerves and alleviate the strains of daily travail. In 1955, Columbia followed with a four-album series called Music for Gra- cious Living that included the arpeggios of Peter Barclay and His Orchestra, along with back cover recipes for buffets, bridge games or barbecues.

1950s background music album titles

- Light and Lively

- Bright and Bouncy

- Show Tunes

- Songs We Remember

With liner notes ““Early in the evening, when the hostess is struggling to get the party off the ground, the music will fill those embarrassing lulls.””

Supermarket Symphonette

Step lively to a kinder and gentler Swing, elevated and swathed in a moderate tempo to keep you energized but never distracted. More to the beat of drum majorettes than jam sessions, this is heartland- of-America music, touching even hearts that have long been cold or broken…

Composer Ray Conniff comes closest to furnish music that is “to the supermarket born”

Conniffs music connotes the mystically metallic clanking of shop- ping carts trailing down aisles, the rustle of cash registers, the tinkle of loose change, and the grunt of chromium doors auto- matically opening for the next phalanx of shoppers. Conniff’s me- ticulous, up-tempo, and regimented beat has a chilly innocence— the perfect soundtrack for patrons traipsing under Safeway or A&P klieglights.

Discovery of a “ghost tune” behind the apparent one:

I tried to figure out a hit solution. I bought eight or ten records like Artie Shaw’s “Begin the Beguine” and Glenn Miller’s “In the Mood,” listened over and over, looked for a trend running through, listened for a week; nothing registered. Then after work one day, something hit me. In 80 percent of the records, either the song or background score had recurring patterns. At that time the advertisers would punch “Id walk a mile for a Camel,” “Ivory soap, it floats!”—repetitious stuff.

Walls Talk

Muzak served 43 of the world’s 50 biggest industrial companies, and the US Armed force listed Muzak among its “Optional Equipment” as Polaris submarines played Muzak to ease crew pressures. Buzz Aldrin and Neil Armstrong listened to it on their Apollo lunar cruise.

Its efforts to use tempo and timbre to reflect parts of day and to adjust them to the human “fatigue cycle” reveal how walls, corridors, lighting, and the contours of man-made enclosures alter our perceptions and _biorhythms.

Throughout the 60s Muzak conducted experiments investigating music to influence group behavior.

The Ascending curve proved most successful.

Around 1972, Muzak engineer Paul Warner concocted Muzak-Controlled-Time, a plan intended to synchronize the world’s clocks so that not a second would go to waste. With the help of Bulova, Warner had built a model of the clock on Long Island. The idea was that subscribers to the music service could hook into a signal that would send a cycle-pulse from a satellite network through a Muzak radio network that was tied to Greenwich Mean Time.

There were concerns about subliminals and brainwashing.

Functional music:

“Muzak no longer thinks of itself as just nice, bland background music with no commercials. Today, we think of music as our raw material. Our service actually lies in its sequential arrangement to gain certain effects and to serve a functional purpose.”

Boring work is made less boring by boring music.

Background music used monaural transmission systems, despite being recorded in stereo. The result is a series of ceiling sound-vents emitting exactly the same depth of sound and frequency.

A fast-food outlet like McDonald’s, with its large turnover of patrons, may tend to pipe in up-tempo music to encourage fast eating and fast exit; while a supermarket may play a lower-tempo selection to encourage shoppers to linger over items that might otherwise be overlooked.

Another study, fast tempo music made people eat faster, but slow tempo music did not make them eat slower.

Muzak conclusions in ICU Unit St. Josephs in Yonkers

an emphasis upon major modes, rather than minor modes; tunes that were melodious, but not sad or som- ber; music that would not evoke wistful reminiscences about the “good old days”; and music that would be bright and melodious, yet not exciting. Their rhythm had to be regular, although not predominant, with enough variation to avoid monotony. Variations in loudness were controlled in the music programs to insure that no sudden loud musical peaks would precipitate a fatal cardiac arrhythmia.

Beautiful Music movement lead to Space Age or New-Age music, which did away with the familiar melodies, passing off their music as purely artistic.

Space music can then be best regarded as an outgrowth of easylistening that is even further removed from the musical foreground. Beautiful Music supplies ghost tunes of originals, whereas space music distills the ghost tune’s mood, its sound, and a smidgen of its style and reprocesses it into an “original” composition once again, this time unanchored to any distinct emotional or historical context. It avoids nostalgia mainly because its uncertainties force us to look back and ahead simultaneously. It derives power from the clash between the musician’s emotions and the spacestation grandeur of high-tech gadgets and computer wizardry.

Elevator Noir

Muzak programmers and engineers, who once used only major chords, were always aware that the simplest audio nuance could set off a lachrymose tone.

Muzak had to be deleted from in-flight services, like “Stormy Weather”, “I”ve Got a Feeling I’m Falling” etc.

Elevator Noir was darker melodies and anti-melodies.

Director David Lynch and composer Angelo Badalamenti collaborated on their own blend of easy-listening irony on the soundtrack to the now legendary television series Twin Peaks.

“A good example is in the movie Fire Walk with Me,” Badalamenti reflects. “Laura Palmer is walking by a tree-lined street; the birds are in the trees, singing happily; she’s carrying her schoolbooks. There is a cut on the soundtrack, a montage, which starts out so nice and pretty, but then you have all this high-string dissonance against it. It reflects that whole internal thing that this young teenager has gone through in her world. It paints the various worlds. From up above, down below, and everything in between.”

Since Muzak tracks imitated existing tracks, they were a target for licensing enforcement

rel:Survey of Vandal, Fake and Replica

Before the vogue for “sampling” threatened all conventional boundaries of musical custody, many recording artists and songwriters were aware that an instrumental imitation could be the highest form of financial flattery.

The benefits of cohesive style, shorn of edges:

While the originals were too specific, carried too much baggage, or made for a cluttered audio perspective, the elevator version provided audio depth of field, an appropriately vague contour for transient surroundings.

Nick Perito

It’s sad to think that this kind of background music is no longer around. Muzak was the blend that tried to fit ev- erything. We liked to think that we were giving people pleasant memories. The music was a wonderful balm for the up and going, the frantic, the running, the hurried. Muzak was “making nice,” putting a little shawl around you. It didn’t attack or provoke. When we recorded Muzak music, I liked to think that we weren’t going to war; we were going to the peace table.