created 2025-03-17, & modified, =this.modified

rel: Theo Lutz - Stochastische Texte Text Generation and Other Uneasy Human-Machine Collaborations Code Poems

Why I’m reading

We’ve gone from digital poetry from being an esoteric tech art, to something that everyone does as one of their first prompts on an LLM. How does this proto form (though distinctly a different type of project), compare to LLMs?

I want to know more on the history of these earlier works. I believe I heard of this book first as a reference in anothery2025 read, but I cannot at this time recall which.

The copyright of my edition is 2007.

Prehistoric Digital Poetry - An Archaeology of Forms, 1959 - 1995

To my comrades in the present and to cybernetic literary paleontologists of the mythic future

Foreword

For the true skeptics—and they do exist—digital poetry is an impossibility. In this view the computer is intrinsically unsuited for the creative act of writing poetry for a variety of reasons, ranging from the fact of its strict programming to the inverse fact of its lack of a structure for invention. A milder version of this position sees no real poetry yet written in digital media—all ®ash and no creativity, at least so far.

Chronology of Works in Digital Poetry

- 1959 - first computer poems, Theo Lutz - Stochastische Texte

- 1960 - Oulipo founded

- 1961 - Nanni Balestrini’s “Tape Mark I” created with code and punched cards on IBM 7070 …

Digital poetry is a new genre of literary, visual, and sonic art launched by poets who began to experiment with computers in the late 1950s.

Crucially, this book demonstrates digital poetry was founded mechanically, and conceptually, decades before personal computers and WWW came into existence.

Digital poetics is not one form but a conglomeration of forms, also “contemporary digital poetry merely refines earlier types of production and disseminates works to a wider audience via the network.”

These works are obscure:

Digital poems made in this period were part of a substratum of contemporary art, overshadowed by the abundance of dynamic works produced by writers and artists whose more accessible surfaces (such as books and galleries) gained much broader exposure.

French symbolist writing, particularly Stéphane Mallarmé’s late-nineteenth- century poem “A Throw of the Dice Never Will Abolish Chance” (1897), is unquestionably an artistic antecedent that directly impresses upon the disruption of textual space and syntax found in digital poetry. The variations in typography, incorporation of blank space, and the liberal scattering of lines often found in digital poems can be discerned as having roots in Mallarmé’s work.

Styles - permutations, playing with space, database reference,.

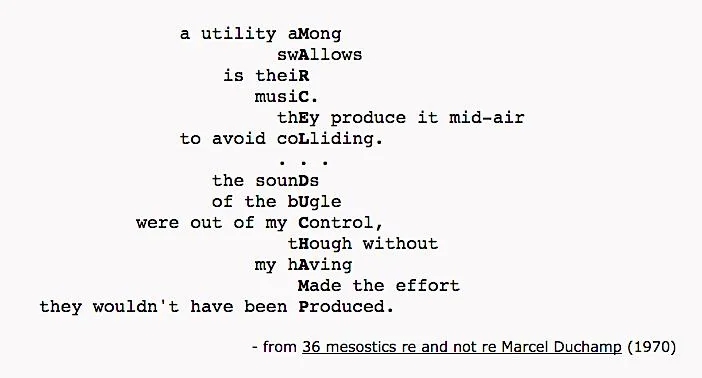

Another style - emulates the dadaist practice of reordering the words of one text in order to make a new text, which has been called “matrix” poetry by several practitioners. This approach invites and permits poets to use previously composed texts within new, perhaps seemingly unrelated, contexts, as Duchamp did.

Hypertexts, however, are often self-contained, despite the fact that they consist of many fragments. The links embedded, and maps of texts provided, are not used expansively but rather referentially (toward building overall coherence), despite the narrative and thematic rupture brought on by the linking mechanism.

Critics have cited hypertext’s disorienting properties as a form of aesthetic pleasure and propose that discovery, invention, and interpretation often begin with a sense of confusion.

Digital poetry “applies to artistic projects that deal with the medial changes in language and language-based communication in computers and digital networks. Digital poetry thus refers to creative, experimental, playful and also critical language art involving programming, multimedia, animation, interactivity, and net communication.

Tech Framework

In the 1960s authors programmed poems using coding designed for math and science. Programs were run out of necessity on institutional or corporate mainframes (costing more than $100K) without GUIs or computer mice.

Origination

On automatic digital poetry:

the sole responsibility of the poet is to provide random input and a coded description of the desired output poems or poem. The poet using the program is freed of concerns of order and organization, and feed from the need for insight or direction.

Author has trouble with this viewpoint:

“The results of these experiments and the actual processes in the machine were actually less significant than the question as to how to interpret automatic text generation with respect to its aesthetic functions, such as relative to the creativity of a human author”

Historical Forebears

Dadaism had principles of revolt, disgusts, pullback from the absolute and the process of denaturalization.

MERZ poems by Kurt Schwitters made poems out of “the sounds of coughs and sneezes” and “collages from found objects”.

Tristian Tzara’s “How to Write a Dada poem” instructed readers to cut up articles into individual words, and make a poem by randomized selection and reorganization.

All of these elements have a place in historical digital poetry.

rel: Oulipo

Oulipo advanced forms of noncomputerized procedural poetry and writing that employed arithmetic. Oulipo pursued “potential” literature, developing a single formula could lead to an unlimited number of works. Writing of members was often restrictive.

One example, the n+7 poem, nouns were replaced with the seventh noun that falls after it in the dictionary.

First Digital Poems

rel:Theo Lutz - Stochastische Texte

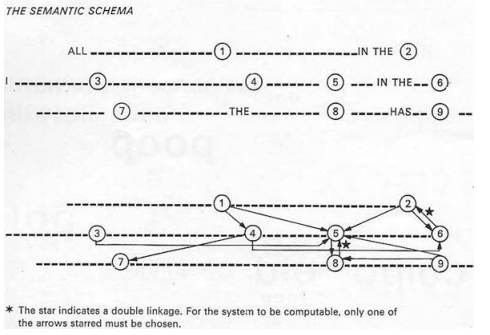

Lutz made a database of sixteen subjects and sixteen titles from Franz Kafka’s novel The Castle. Lutz’s program randomly generated a sequence of numbers, pulled up each of the subjects/titles, and connected them using logical constants (gender, conjunction, etc.) in order to create syntax:

Not every look is near. No village is late.

A Castle is free and every farmer is distant.

Every stranger is distant. A day is late.

Every house is dark. An eye is deep.

Not every castle is old. Every day is old.

Not every guest is furious. A church is narrow.

No house is open and not every church is quiet.

Not every eye is furious. No look is new.

We see unusual semantic connections, “no village is late.”

Three essential stages of these early texts

- determine a frame (single word, stanza or grammatical features)

- creating a dictionary of words for use in the frame

- adding extra qualities or instructions (rules, such as for rhyming)

Brion Gysin’s “I Am That I Am” permutated

I AM THAT I AM

I THAT AM I AM

I AM I THAT AM

I I AM THAT AM

I THAT I AM AM

I I THAT AM AM

I AM THAT AM I

I THAT AM AM I

I AM AM THAT I

I AM AM THAT I

I THAT AM AM I

I AM THAT AM I

I AM I AM THAT

I I AM AM THAT.

The permuted poems set the words spinning off on their own; echoing out as the words of a potent phrase are permuted into an expanding ripple of meanings which they did not seem to be capable of when they were struck and then stuck into that phrase

Thought

The Godel Encoding, some relationship here to the encoding done with these generative texts?

Alan Sondheim created several inventive conceptual works in the 1970s, including poems he produced by programming a calculator to perform language generation.

A single phrase is introduced and permuted as other phrases, and sentiments are briefly introduced and processed. In this example the poem verbally and visually diminishes as the program produces output, before expanding again at the end.

Hysterical activity, art, hernow and then

Hystercal activity, art, hernow and then

Hysterical actvity, art, hernow and then

Hysterical activity, art, hernow and athen

Hysterical activity, art, hernow and an

You might ¤ndnow and then

You msheight ¤ndnow and then

You mshesheight ¤ndnow and then

You msheshesheight ¤ndnow and then

You msheshesheight ¤ndnow and then

Ors against her smooth body

Ors againssmooth body

Againssmooth body

Ainssmooth body

Ssmooth body

Ooth body

H body

Ody

A chance encountera touching reminder

A chance encounouching reminder.

Thought

Fizzbuzz, the test of competency conjured by programmers worldwide, a poem? Is it a form of a poem? All of the various implementations (Rosetta Code) make up a different way of writing the same poem.

Verse Forms

Of all the verse forms attempted to be programmed, haiku has dominated, probably because of formulaic limitations.

As both poets and programmers have realized, for different reasons, the reader’s mind works most actively on sparse materials.

Example:

I smell dark pools in the trees

crash the moon has fled.

This is the “slot” system of composition, akin to madlibs.

Thought

Even though they are odd, at least reading these, I find them more attractive than something more “artfully” constructed, and attractive like ChatGPT with a prompt.

The creators and readers of these poems might not have even thought highly of the output, viewing it more like an exercise.

But even if it’s just a dictionary and structure, completely chosen at random by computer and human, I find it a more curious object.

Throughout reading this, I have ideas of generative poems to make and experiments involving words and rules. I say to myself “Really does this have a place? Would this just be antiquated when I can use an AI to produce all the pseudo-poems I want?”

What I find is yes.

Thought

The modern computer form (submission) as a type of poem, in the “slot” system sense.

The idea of a form.

When you submit data to a form, you are adhering to the rules of the form and that data is molded into a shape.

If all submissions to forms were done, label-less what would happen? If we abandoned strict rule structure to input (as some universal constraint, like we forgot the value of it or never evolved it) what would happen?

Slotted Works

“A House of Dust” (1968), written by Alison Knowles and James Tenney, is among the first poems featuring collocation via a programmed slot-system.

A HOUSE OF PLASTIC

IN A PLACE WITH BOTH HEAVY RAIN AND BRIGHT SUN

USING CANDLES

INHABITED BY COLLECTORS OF ALL TYPES.

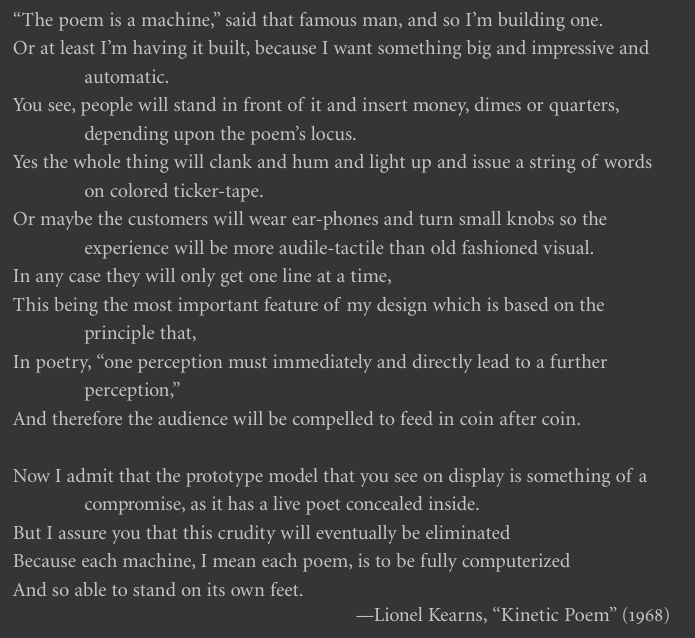

John Cage began working with computer programming. Computers provided an excellent vehicle for Cage’s work; since his 1953 composition Music of Changes he had promoted the concept of nonintention in art, a process in which the artist is no longer required to make decisions in her or his compositions but rather lets chance control creative expression.

He composes or identifies a source text that he uses as an “oracle” and asks it what words to use for each.

Merz Poems (2004)

Bits of words are selected and rearranged, offering no possibility for conventional words or linguistic clarity, as in this example:

bmf

b dbd

jvev

z vp xxiiss z jahks

rhx mwpso qkwim.

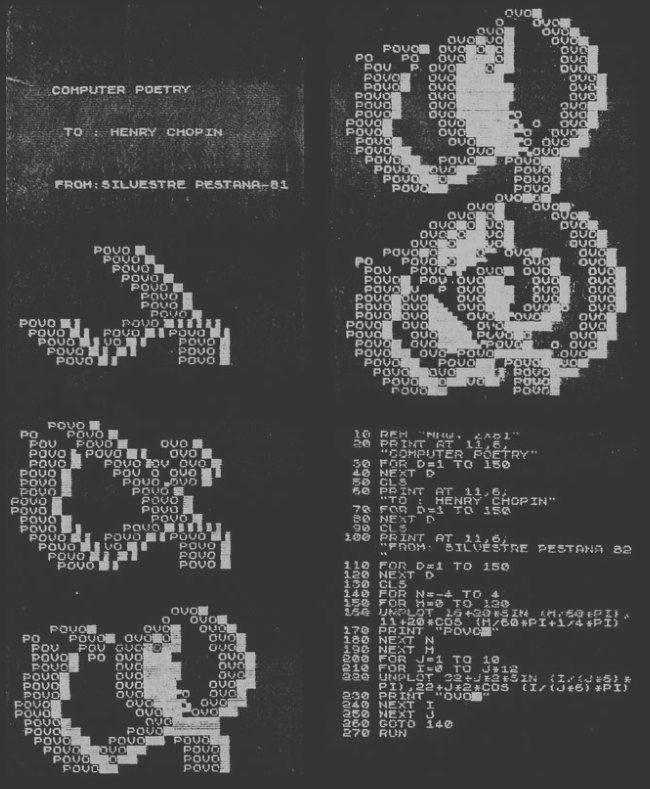

The generation of a computer poem is a fusion between the software/ algorithm and the interface. The materials transform a set of words in a database into contours of poetic expression. The production of serial texts and mutations and manipulations of the language in a database open the possibility of a continuous perpetuation of language and ideas. Writing a computer program that will generate captivating text involves multiple imaginative steps.

Visual and Kinetic Digital Poems

New kinetics and interactivity of words.

In the 60s these works largely employed mutation as opposed to permutation. Static and kinetic visual works introduced a poetry of sight, overtly conscious of its look, sited on and incited by computers; standard typefaces became a thing of the past. Digital poets (and those working with video and holography) began to work with poetry that was literally in motion.

Concrete Poetry (exploration of visual semiotics in Germany/Brazil in the 50s) was a historical forebear.

Talk of UbuWeb rel:In Defense of the Poor Image by Hito Steyerl

Ingmar Bergan: (Film Has Nothing to Do with Literature)

Film has nothing to do with literature; the character and substance of the two art forms are usually in conflict. This probably has something to do with the receptive process of the mind. The written word is read and assimilated by a conscious act of the will in alliance with the intellect; little by little it affects the imagination and the emotions. The process is different with a motion picture. When we experience a film, we consciously prime ourselves for illusion. Putting aside will and intellect, we make way for it in our imagination.

Thought

You can feel the difference between Written text and spoken text, but maybe the divide is different than what Ingmar says.

If I only read nonfiction, then encountered a fantasy book, would my read be different?

Literature might also require immediate submission to function.

How many times does my mind wander in each? Maybe this avenue: a film in a theatre moves without you. It doesn’t wait for you to catch up, something on the screen brings out a memory, and when you return the film has moved on. This happens when reading a book, possibly more often? (Reading a passage, thinking something and returning back to a part of the page that washed over you, you cannot even recall despite your eyes tracing the page before). But with a book you are afforded that return more easily. It is an iterative format.

Even when writing this, I read the Ingmar quote multiple times, over and over again. Each time it changes. I can feel bits of places I can think of it, like vague clouds in my head that excite me. If I sat, and read it over and over again, with the effort and chasing that excitement, I am sure something new would emerge. Some kind of different understanding.

Technological Conditions

Print technology enabling:

Printed output has been possible since the development of dot matrix printers in 1957. Thermal printers (1966), digital typesetting (1968), laser printing (1980), and color laser printing (1988) all played a role in heighten- ing the quality and aesthetics of visual works.

“Some people have tried to create shape poems with a typewriter. No one could write the shapes I write without a computer.”

Presenting the poem and code together both documents the process and reflects the product.

Animation of the text:

Though impossible to capture in a still image, the animated and mimic qualities are impressive; “Amour” resembles a movie in that a verbal drama unfolds as the poem progresses… type of choreography associated with dance and with the movement of sand traveling across a windblown beach, which always “entombs” the poet.

One of the first is an enigmatic piece that requires viewers to investigate the basic structure presented on the screen but only allows them to accomplish one of two tasks: to either erase characters that they have typed or to erase part of a phrase that the program presents.

Hypertext and Hypermedia

Ted Nelson wrote hypertext was proposed as a practical proposition: using computer storage and display mechanisms, writers could create multiple “branching” and alternative structures in their work and allow viewers to navigate through them.

Hypertext means non-sequential writing. Hypermedia - A formal expansion of hypertext, hyper- media consists of visual, alphabetic, and audio components and performs in dimensions that printed formats do not allow.

- hyperfilms

- branching audio/music

- branching slide shows

Historical Forebears

Hypertext can never be adequately represented in film, but there are precursors.

- Tristram Shandy by Laurennce Sterne

- Hopscotch by Julio Cortazar

- Blakes Four Zoas

- James Joyce, Italo Calvino, Borges, Marc Saporta, Choose your own adventure books

Tech Conditions

Doug Englebart created the first hypertext system, “Augment” in 1968. Hypertext program - “Storybook” - “hypertext writers can create documents that respond to individual reader needs and interests, offering readers a range of choices instead of imposing a single, fixed approach”

Exploratory Poems

Hypertext is a visual form, recorded in the form of collage (though sometimes only in the form of maps.)

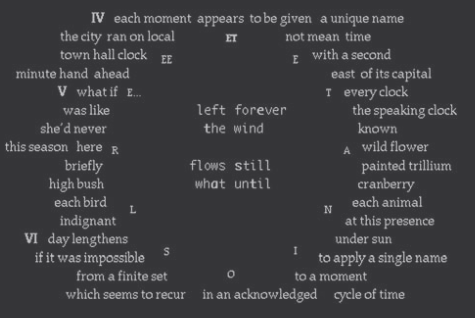

The Speaking Clock

The program selects words from these texts that contain the letter that corresponds with the momentary time and date; the word is placed in sequence in the area in the middle of the “clock,” with the signifying letter emboldened.

What if it was impossible to apply a single name from a finite set to a moment which seems to recur in an acknowledged cycle of time? What if it was impossible to apply the word ‘dawn’ to more than one single instant at the beginning of some one particular day?”

Xanadu:

From the beginning Nelson envisioned a computer network in which all of the world’s texts (in all media) were interconnected into one grand document via computer networks.

Alternative Arrangements

During the 1980s, however, several digital technologies and techniques evolved that had poetic signi¤cance. Digital sampling (the process of cutting and processing segments of recordings), the CD, Musical Instrument Design Interface (MIDI), Digital Audio Tape, and Minidisc formats and tools were all available by 1990, though because of their cost they were for the most part only available to artists with corporate support.

I have yet to encounter a digital poem in which interactivity is engaged by the viewer’s spoken voice.

Techniques Enabled

The past must be invented. The future must be revised. Doing both makes what the present is. Discovery never stops John Cage

False:

1977, Carole Spearin McCauley wrote: “I don’t predict a great future community among writers, computers, and computer programmers. Computer time is expensive, few writers are yet their own programmers, and programmers may not possess the kind of minds that want to produce creative literature. Literary experimentation can be an uncertain process, requiring the species of poetic, unprosaic mind that is happy with unfixed parameters, serendipitous juxtapositions, no-definite-end-goal-from-the-beginning”