created, $=dv.current().file.ctime & modified, =this.modified

tags:surrealism

Author philosophizes: Would a book devoted to women unnecessarily isolate and perpetuate their exile?

Meret Oppenheim has specifically requested that no work of hers be reproduced in this book. Arguing that the “male centeredness” of the Surrealist group merely reflected the inheritance of late-nineteenth-century attitudes toward women, and that the Surrealists accepted female artists and writers without prejudice, she goes on to say:

When I met the group, end of 1933, I was twenty years old and I was not at all sure about political opinions. I made my work and did not worry about these discussions. (After the war I met Man Ray again. He said to me: “But you are speaking!” I asked him: “Why do you say that?” He answered: “You never said a word formerly.”) Concerning the theme of the “Muse” I want to say: the “Muse” is an allegorical representation of the spiritual female part in the creative male, the “genius.” And the “genius” represents the spiritual male part in the creative female, the “Muse.”… Personally I consider the problem of female versus male as solved, although I know that many have not arrived at this point.

Search for a muse

Surrealism, a collective adventure committed to nothing less than the complete transformation of human values, remained strident in its demand for the liberation of consciousness from the bondage of Western civilization. Yet the Surrealist revolution failed in its bid to resolve the conflict between a nineteenth-century image of woman as passive, dependent, and defined through her relationship to an active male presence, and a more contemporary demand for female autonomy and independence.

Surrealism struggled with the inconsistencies of its own polarized visions of woman: one Romantic, the other revolutionary.

Gala

Though not an artist, Gala became the first incarnation of the Surrealist muse. While she was married to Eluard, Max Ernst fell in love with her and, in 1922, left his wife to follow Gala to Paris where he included her image in a painting commemorating his reunion with the Surrealist poets. Dali met her in 1929; soon he incorporated her image and her reality into a mythologized vision of the salvationary heroine, and she appears in this guise in many of his paintings of the 1930s.

Nadja - Andre Breton

“Hysteria is not a pathological phenomenon and can in every way be considered as a supreme means of Expression,”

Hysteria: beginning of the twentieth century, was still believed to be an almost exclusively female affliction. Freud himself believed that Hysteria resulted from an inability to release sexual excitement through normal channels and from the subsequent transformation of the repressed energy into physical symptoms.

In his study of Hysteria, Janet called the ecstatic states of his female patients amour fou, or mad love; his vision became the basis for Breton’s belief in the transformative power of the ecstatic state, at once erotic and irrational.

I do not see the (woman) hidden in the forest

Here the nude figure of a woman is reproduced at the center of a group of sixteen Surrealist painters and poets who close their eyes to the exterior world and pay silent homage to the muse within. Perhaps the reference is to Nadja in which Breton tells us that he had always hoped “to meet at night and in a woods, a beautiful naked woman.”

Lee Miller and Man Ray

She brought to photography a lingering belief that it was an art inferior to painting—a view shared by Man Ray—and she once volunteered to do all the studio photography and tedious darkroom work herself in order to free him to paint.

So close was their collaboration between 1929 and 1932 that often they could not remember which one of them had made a particular image.

Accidentally discovering solarized photographs:

Something crawled across my foot in the darkroom and I let out a yell and turned on the light. I never did find out what it was, a mouse or what. Then I quickly realized that the film was totally exposed: there in the development tanks, ready to be taken out, were a dozen practically fully-developed negatives of a nude against a black background. Man Ray grabbed them, put them in the hypo and looked at them later. He didn’t even bother to baw] me out, since I was so sunk. When he looked at them, the unexposed parts of the negative, which had been the black background, had been exposed by this sharp light that had been turned on and they had developed, and came right up to the edge of the white, nude body. … It was all very well my making that one accidental discovery, but then Man had to set about how to control it and make it come out exactly the way he wanted each time.

Miller’s image, immortalized in photographs by Man Ray, is better known today than is her own work, about which she remained self-effacing for many years, finally abandoning it altogether.

rel:Dora Maar

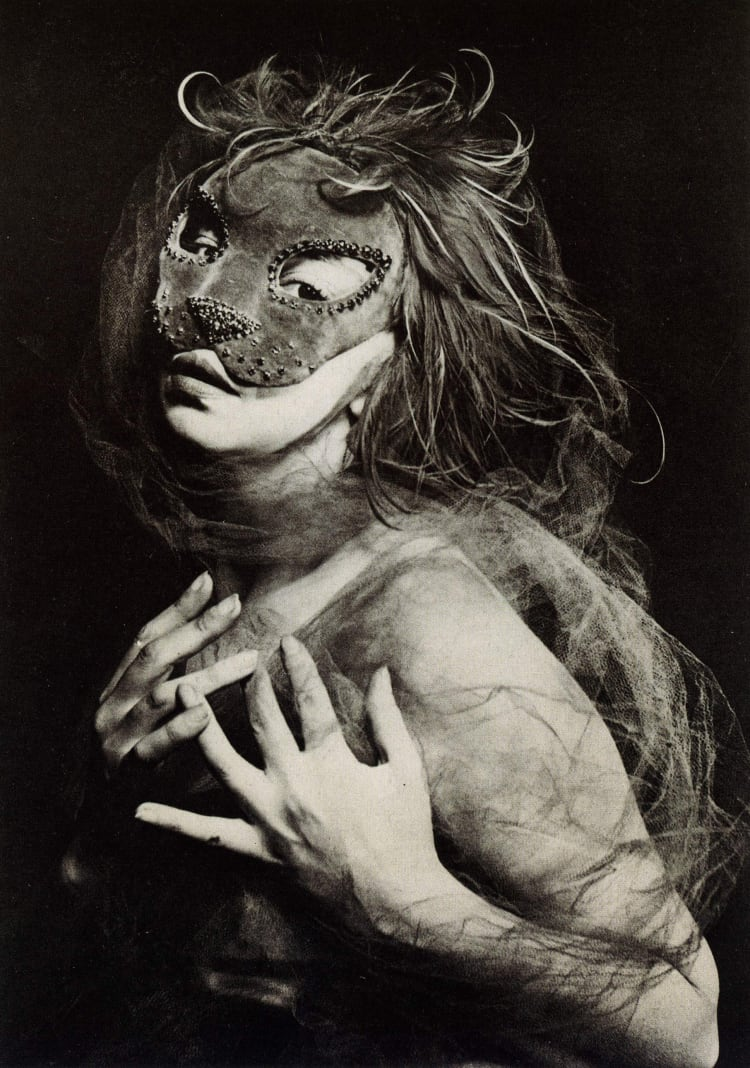

When elaborate hairstyles were the rage in Paris, Dora Maar, a young painter and photographer who was close to the group in 1936 and 1937, arrived at the Café de la Place Blanche with her hair disheveled and falling down over her face and shoulders, like someone just rescued from drowning. At the Surrealists’ table; relates Marcel Jean, everyone—or nearly everyone—exclaimed in admiration.’

Henry McBride wrote that the women were better than the male Surrealists he had seen, but his remarks are not to be taken seriously as he went on to say: “This is logical now that one comes to think of it. Surrealism is about 70 percent hysterics, 20 percent literature, and 5 percent good painting and 5 percent is just saying ‘boo’ to the innocent public. There are, as we all know, plenty of men among the New York neurotics but we also know that there are still more women among them. … It is obvious that women ought to excel at Surrealism. At all events, they do.”

The role of the woman artist as a creator in her own right can be sought only in her works.

The Muse as Artist

I didn’t have time to be anyone’s muse … I was too busy rebelling against my family and learning to be an artist. - Leonora Carringtonquote

Bretonquote

Everything leads me to believe, that there exists a point in the human mind at which life and death, the real and the imaginary, the past and the future, the communicable and the incommunicable, the high and the low cease being perceived as contradictions.

Daliquote

The only difference between myself an a madman is that I am not mad.

Leonora Carrington

The British writer and painter Carrington met Max Ernst in London in 1937. He left his wife for Carrington, his “Bride of the Wind.” The couple lived together at St. Martin d’Ardéche until the outbreak of World War II and Ernst’s internment as an enemy alien. Institutionalized following a breakdown in 1940, Carrington later fled to New York and Mexico where she developed a close and productive friendship with Varo. Carrington’s work during this period moves from themes of childhood, filled with magical birds and animals, to a mature art based on Celtic mythology and alchemical transformation. It is an art of sensibility rather than hallucination, one in which animal guides lead the way out of a world of men who don’t know magic, fear of the night, and no mental powers except intellect.

Leonor Fini

A painting is something like a spectacle, a theater piece in which each figure plays out her part.

Fini herself never accepted the label of “woman artist,” and likewise, never considered herself a Surrealist.

Thought

It looks like there was an exhibition of Leonor Fifi at the Kasmin Gallery in 2023 I missed.

Back to Leonora: Carrington’s first meeting with Ernst in New York occurred by chance at the Pierre Matisse gallery. The experience caused both of them deep unhappiness. “I don’t recall ever again seeing such a strange mixture of desolation and euphoria in my father’s face as when he returned from his first meeting with Leonora in New York,” Ernst’s son, Jimmy, later recorded. “One moment he was the man I remembered from Paris—alive, glowing, witty and at peace—and then I saw in his face the dreadful nightmare that so often comes with waking. Each day that he saw her, and it was often, ended the same way.

Fini: Fini refused to accept a world defined by male institutions and she revolted by placing not just her own image at the center of her work, but images of other women as well. She turned her back on marriage to avoid submitting to an institution she found patriarchal, and she used painting as a vehicle for creating a world animated by woman’s desires; “I always imagined that I would have a life very different from the one imagined for me, but I understood from a very early time that I would have to revolt in order to make that life,’

Frida Kahlo

Kahlo called herself a Realist who painted her own life. Much of her reality was bound up in the figure of Diego Rivera with whom she lived a rich and tempestuous life despite years of suffering brought on by an early accident. She was often photographed as an image of exotic beauty and the exquisite wife of Mexico’s most famous painter; her own vision of herself was Starker, In 1939 she was working on The Two Fridas when she received final divorce papers from Rivera. The two Fridas— one loved, the other not—are joined by hearts that bleed over the loss of Rivera, included in a miniature photograph taken when he was a child and held by the Frida who wears a Tehuana skirt and blouse. In this portrait Rivera has disappeared from Kablo’s life; she is accompanied by herself and holds only mementos of their life together.

Revolution and Sexuality

The Surrealist love of costume, or the lack thereof, proved a perfect forum for inventive, and often sexual, display.

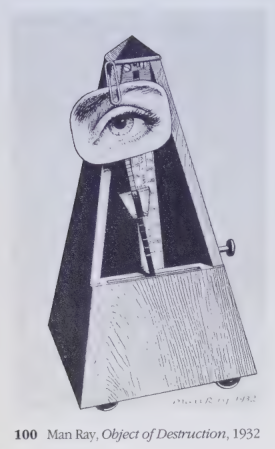

Lee Miller told me she had met a man who liked to whip women—it was nothing new for her.”‘’ Two years later, his anger at Miller, who had decided to leave Paris and open her own photographic studio in New York, would erupt metaphorically in the so-called Object of Destruction (1932). Cutting out a photograph of Miller’s eye, the photographer’s most vital and most vulnerable organ, he attached it to the arm of a metronome with an invitation to the spectator to “destroy this object.”

rel: Automatism Limits, Detecting an Edit Emmy Bridgwater

Bridgwater, Lamba, and Rabon used automatic techniques to liberate the imagery of the unconscious, and they recognized the affinity between automatism and the mysterious transformations of matter and form that take place in nature.