created 2025-02-18, & modified, =this.modified

tags:y2025generativeartscience

rel: Text Generation and Other Uneasy Human-Machine Collaborations Max Bense

NOTE

In this very early state of generative texts, the root of issues we currently deal with are present.

Although program-controlled, electronic data processors were initially developed to satisfy the needs of applied mathematics and computational engineering, it was soon apparent that the possible system applications could far exceed these limits.

Non the less, many scientists are still under the false impression that the use of electronic data processors is bound to the use of numbers. A variety of programs has shown, however, that such an assumption is incorrect.

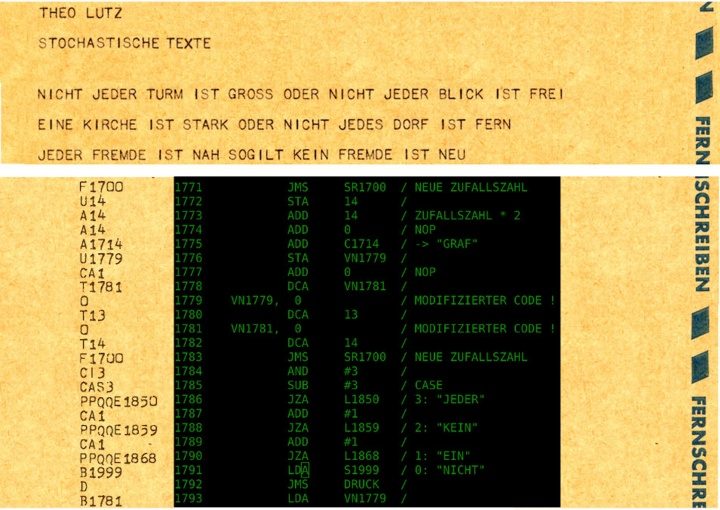

At this stage we shall report on a program which the author recently executed on the electronic mainframe ZUSE Z 22 at the T.H. Stuttgart computer center. The machine was used to generate stochastic texts i.e. sentences where the words are determined randomly. The Z 22 is especially suited to applications in extra-mathematical areas. It is particularly suited to programs with a very logical structure i.e. for programs containing many logical decisions. The machine’s ability to be able to print the results immediately, on demand, on a teleprinter is ideal for scientific problems.

Our program’s task was to take over the laborious production of stochastic texts. In the past such texts were determined by selecting sentences or constituents of a sentence by throwing dice, or using some other random process, and then connecting these. It seemed reasonable for the program-controlled data processor to work with so-called random numbers, as a stochastic process.

It should be pointed out that this program - it consisted of approx 50 single commands without text - is expandable in various ways e.g. it is possible, within the pre-defined amount of subjects and predicates, to highlight words occurring more frequently, by storing them several times. The arising text will contain these words in a corresponding frequency. Furthermore, the basic amount of words can be selected with regard to a specific language. The machine then produces sentences in this language.

Important:

It seems to be very significant that it is possible to change the underlying word quantity into a “word field” using an assigned probability matrix, and to require the machine to print only those sentences where a probability exists between the subject and the predicate which exceeds a certain value. In this way it is possible to produce a text which is “meaningful” in relation to the underlying matrix.

Such a rectangular matrix contains e.g. the so-called transition probability of subject m to predicate n at point (m, n) i.e. this is a correlation number between these two constituent parts of a sentence. If one extends the program via a super program so that this is capable of increasing the transition possibilities between subject and predicate in those sentences found to be “meaningful”, and of reducing other probabilities in accordance with the mathematical connection, then the machine has “learned” in a certain way: It prefers certain subject/object combinations during the course of time. The results so far let us hope that program-controlled electronic data processors can be used with great success in language research and analytical language areas. It is to be hoped that the distrust of some more traditionally minded philologists towards the achievements of modern technology will soon make way for widespread and fruitful co-operation.

Example text:

THE COUNT THE STRANGER THE LOOK THE CHURCH

THE CASTLE THE PICTURE THE EYE THE VILLAGE

THE TOWER THE FARMER THE WAY THE GUEST

THE DAY THE HOUSE THE TABLE THE LABOURER

OPEN SILENT STRONG GOOD NARROW NEAR NEW

QUIET FAR DEEP LATE DARK FREE

LARGE OLD ANGRY

NOT EVERY LOOK IS NEAR. NO VILLAGE IS LATE.

A CASTLE IS FREE AND EVERY FARMER IS FAR.

EVERY STRANGER IS FAR. A DAY IS LATE.

EVERY HOUSE IS DARK. AN EYE IS DEEP.

NOT EVERY CASTLE IS OLD. EVERY DAY IS OLD.

NOT EVERY GUEST IS ANGRY: A CHURCH IS NARROW.

NO HOUSE IS OPEN AND NOT EVERY CHURCH IS SILENT.

NOT EVERY EYE IS ANGRY. NO LOOK IS NEW.

EVERY WAY IS NEAR.NOT EVERY CASTLE IS QUIET.

NO TABLE IS NARROW AND EVERY TOWER IS NEW.

EVERY FARMER IS FREE. EVERY FARMER IS NEAR.

NO WAY IS GOOD OR NOT EVERY COUNT IS OPEN.

NOT EVERY DAY IS LARGE. EVERY HOUSE IS SILENT.

A WAY IS GOOD. NOT EVERY COUNT IS DARK.

EVERY STRANGER IS FREE. EVERY VILLAGE IS NEW.

EVERY CASTLE IS FREE. NOT EVERY FARMER IS LARGE.

NOT EVERY TOWER IS LARGE OR NOT EVERY LOOK IS FREE.

A CHURCH IS STRONG OR NOT EVERY VILLAGE IS FAR

EVERY STRANGER IS NEAR THEREFORE NO STRANGER IS OLD

A HOUSE IS OPEN. NO WAY IS OPEN.

A TOWER IS ANGRY. EVERY TABLE IS FREE.

A STRANGER IS QUIET AND NOT EVERY CASTLE IS FREE.

A TABLE IS STRONG AND A LABOURER IS SILENT.

NOT EVERY EYE IS OLD. EVERY DAY IS LARGE.

NO EYE IS OPEN. A FARMER IS QUIET.

NOT EVERY LOOK IS SILENT. NOT EVERY TOWER IS SILENT.

NO VILLAGE IS LATE OR EVERY LABOURER IS GOOD.

NOT EVERY LOOK IS SILENT. A HOUSE IS DARK.

NO COUNT IS QUIET THEREFORE NOT EVERY CHURCH IS ANGRY.

A PICTURE IS FREE OR A STRANGER IS DEEP.

A GUEST IS DEEP AND NO TOWER IS FAR.

A GUEST IS QUIET. EVERY PICTURE IS FAR.

A TABLE IS OPEN. EVERY LABOURER IS FREE.

EVERY TOWER IS NEW AND A PICTURE IS OLD.

NOT EVERY TABLE IS LARGE OR EVERY VILLAGE IS OLD.