created 2025-03-31, & modified, =this.modified

Why I’m reading

Earlier last year I was reading a lot about reading and writing, done in paper and early books.

This ongoing document that I am writing in now, is a kind of Commonplace Book and notebook (like a public journal.) It is segmented into a public document (which is being read and written now), and a private document. It’s purely digital.

So much of my day is writing, and recording. The first step of creating anything for me, often begins with some kind of reading or documentation.

So, I am wondering about the notebook.

Thought

The notebook, which has its evolution documented below, has taken over the world. The internet is the notebook. Social media in particular, is a notebook. Basically the function of the social network page like a diary just got a feature of connecting notebooks rather than being an isolated object.

Before Notebooks (1000 BCE - 1250 CE)

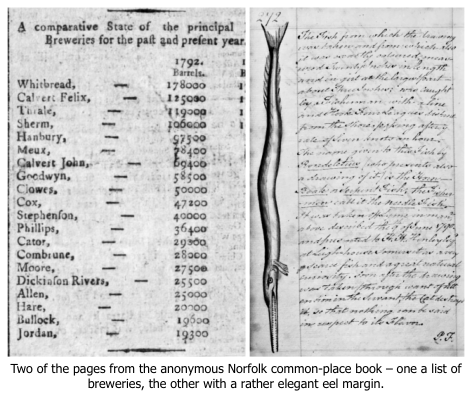

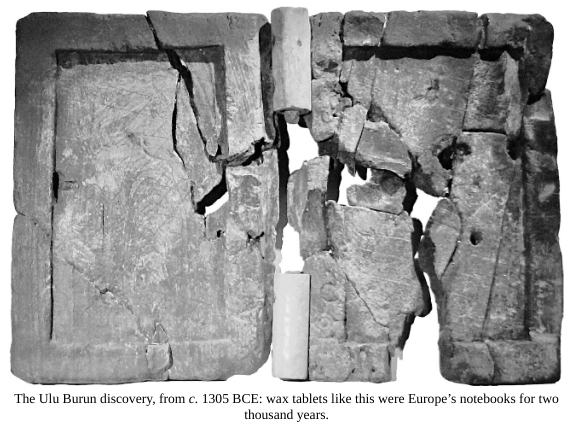

Turkey: The oldest item that looks like a notebook, this tablet – or diptych – was pieced together from many broken parts.

Recesses were cut into two boxwood leaves and these were filled with a layer of soft beeswax, in which the owner could write with a stylus. When they needed to reuse the diptych, its wax could be smoothed over again

We can deduce, therefore, that the tablet’s owner was probably some kind of sailor, trader or diplomat, and cosmopolitan in experience.

In this part of the world for 500 years before this time people had written in cuneiform on clay tablets. These were permanent, tamper-proof records.

In this part of the world for 500 years before this time people had written in cuneiform on clay tablets. These were permanent, tamper-proof records.

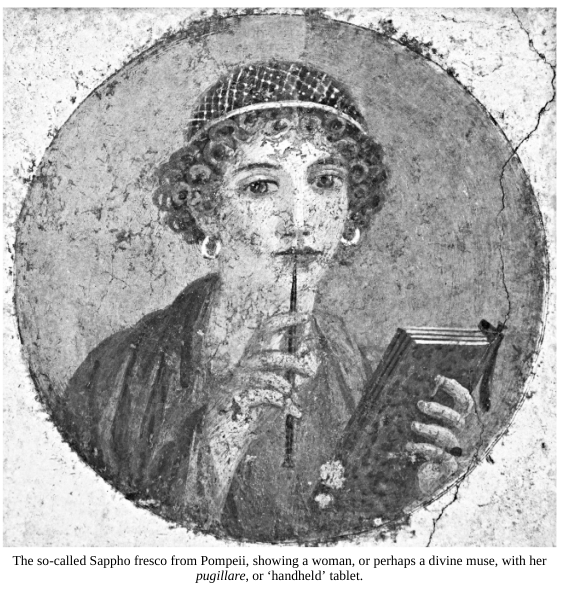

When Roman men are shown with their tablets, the context is always one of business, or the ‘sober management of the family’s wealth’; for women, the picture is more complicated.

This mural is often said to represent Sappho, but the subject might have been a Roman wife keeping her accounts or writing a letter, but recent scholarship argues that she is one of the muses, the divine source of scientific and artistic knowledge.

Men could aspire the the literary life, but their companions could only aspire to inspire it.

For a legible record, Romans went with papyrus, then strips of wood, then parchment (the most durable.)

For a legible record, Romans went with papyrus, then strips of wood, then parchment (the most durable.)

In around 80CE someone in Rome created the first bound book of papyrus pages, the codex.

Thought

80CE, conveniently close to 1CE?

In China, Cai Lun, a Han dynasty eunuch is said to have been responsible for the invention of paper, discovering pulp vegetable fibers drained over a mesh create a durable, affordable, versatile material.

Originally it wasn’t used as writing material (preferring split bamboo, and silk for high status texts).

In Europe most of the literate section of the population were committed to parchment,

They didn’t like paper’s suspiciously infidel origins, its novelty, or its recycled origins: one opponent fulminated against the idea that the word of God could be written on menses-stained rag.

Red Book, White Book, Cloth Book - Invention of Accounting

As an accountant Balancing the books, sounds odd in the world of software like Excel. But we judge a company’s health in terms of their balance sheet.

Farolfi Ledger - Florence in 1300s had

- white book, which was the preceding year’s general ledger

- red book, which was a record of the business in wheat, barley, oats, olive oil, wine wool and yarn

- cloth book, which covered the trade in wool

- two small notebooks for day-to-day expenses

The office had to demonstrate its profitability.

Double Entry Accounting

Today, we are comfortable with the idea of a club, a society, a corporation or a partnership striking a deal, but in the medieval era nearly all accounting entities – apart from the church – were individuals. You were your business, and your business was you.

In the Ledger we see abstract concepts of accountancy along with their practical techniques they were managed. Here is an example of calculation of loss and profit (not just cash and inventory.)

Ink soaked into paper, but dried on parchment (making paper a superior permanent record.)

Sizing - refers to the sheet’s coating. Papermakers of the Islamic world coated their paper with flour and water, which made the paper smoother and less scratchy to write on - but if wet, they turned into glue and the pages stuck together.

The Sketchbook Florence 1300–1500

No-one painted portraits, as we would understand them: subjects identified themselves by their symbolic props, and their size.

Human figures loom over castles, churches and cities, as neither artist nor viewer thought that scale was particularly important, and no-one understood perspective, or made a serious effort to depict the play of light, the fall of cloth or the anatomy of the human body. For the most part, artists didn’t enjoy fame, or wealth: they were craftsmen or clerics, who toiled in a time-honoured sacred tradition and did not aspire to change it.

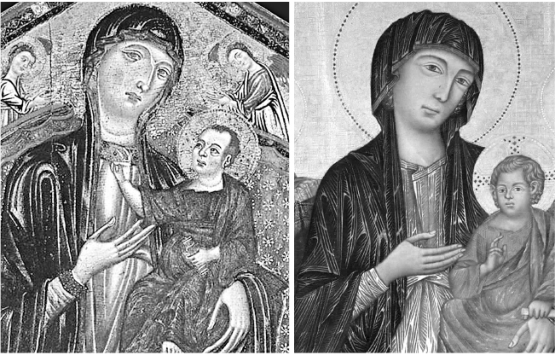

Cimabue and Giotto

Cimabue found his own commissions, and a look at one of his surviving Madonnas reveals how far he advanced the technique of paint, spurning the rote reproduction of religious imagery.

Cimabue, he asserts, unlike his precursors, unlike the Greeks, painted people ‘from nature’ – ‘something new in those days’ – on ‘books and papers’.

Wandering around the Tuscan countryside with a merchant’s ledger and an ink bottle, young Cimabue invented the sketchbook.

The church’s insistence on parchment would have slowed our young artist down, as its physical properties make it a frustrating medium for rapid sketching.

Paper, by comparison, could be used without preparation, and held the line of a stylus, a pen, chalk or charcoal, equally well. You could create shade or the illusion of depth with hatched parallel strokes, and Cennini supplied instructions for dying paper green, pink, grey, blue or purple.

The painting that we admire on a gallery wall is only the tip of an iceberg of studies, sketches, experiments.

Notebooks in the Home Florence 1300-1500

ricordanze - home account book.

Not even illiteracy proved a barrier to keeping a ricordanze. (owner unable to write) instead, when a transaction had to be recorded, he either passed it to a notary or the nearest literate person. The notebook has entries in more than thirty hands. Craftsmen, bankers, friars, priests and school teachers can all be identified, and even a knight of the Order of Jerusalem.

Zibaldone - by the time they completed schooling they kept a book they would maintain their entire lives. Original context means something like jumble, or mess and was referred to “as a salad of many herbs - una insalata di più herbe”

when you found a piece of writing that you liked, or found useful, you copied it out into your personal notebook. You could copy out as much or as little as you wanted, neatly or not, and refer to it a little, or as much, as you wanted.

No two zibaldoni are the same.

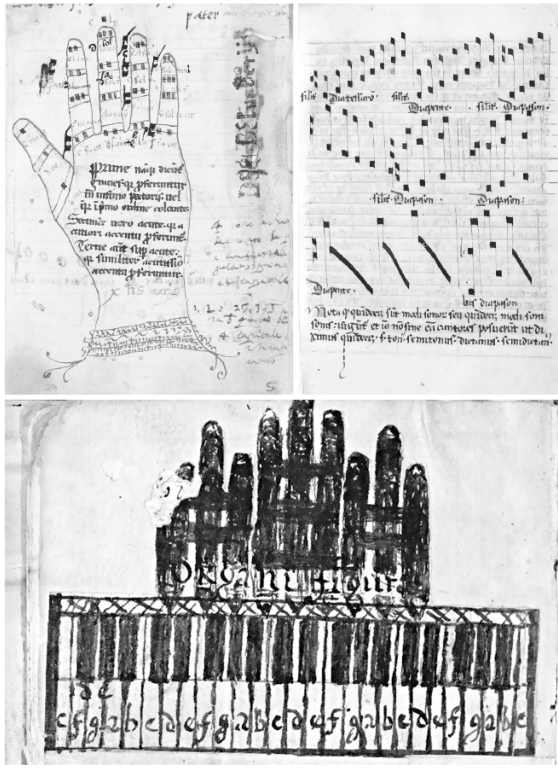

Early composers in notebooks were forced to draw their staves by by hand.

Fundamental theory was passed down from one owner to the next. In this we can see changes in the period of its use:

Fundamental theory was passed down from one owner to the next. In this we can see changes in the period of its use:

It documents the English harmonic innovation known as the gymel, in which two or more voices singing a part in unison suddenly split into polyphonic harmony, producing rich, textured chords before returning to the melody in unison. Gymel demands considerable skill, especially when improvised, as it often was, and English composers and musicians took decades to refine the form over the fourteenth century before it spread to the continent in the fifteenth.

LHD 244’s tips, aimed at players more than composers, show how to add appropriate notes to the bass as it moves up or down the scale, while avoiding accidentally landing on the tritone, an interval so abrasive that it was named diabolus in musica (‘the devil in music’). rel:Tritone

Commonplace Book

Pliny the Elder “never read without taking extracts and used to say that there was never a book so bad that it was good in some passage or another.”

ars excerpendi, the art of excerpting.

People took their common-place books to theater and to church, to preserve the best lines and writers started to self-consciously create quotable texts with common-placing readers in mind - 17th century soundbites. In due course, such truisms became known as ‘commonplace’ and the word quickly became to mean “ordinary” or “unremarkable. ” rel:Stability of Concepts

Thought

That above fact is fantastic. The striking, becomes so diffuse, and exploited that it loses edge and becomes commonplace. Trite.

On Commonplace:

1540s, “a statement generally accepted,” a literal translation of Latin locus communis, itself a translation of Greek koinos topos “general topic,” in logic, “general theme applicable to many particular cases.” See common (adj.) + place (n.). Meaning “memorandum of something that is likely to be again referred to, striking or notable passage” is from 1560s; hence commonplace-book (1570s) in which such were written down. Meaning “well-known, customary, or obvious remark; statement regularly made on certain occasions” is from 1550s. The adjectival sense of “having nothing original” dates from c. 1600.

Ponderous and overwritten text

Only occasional voices dissented. One London contemporary of Swift’s, Henry Felton, called common-placing ‘a Stupid Undertaking’, exclaiming ‘What Heaps of this Rubbish have I seen! O the Pains and Labour to record what other People have said, that is taken by those, who have nothing to say themselves!’

Commonplace books fell out of favor as the diary and the sketchbook became more popular.

Common-placing changes the way people navigated the modern era: “They broke texts into fragments and assembled them into new patterns.” “They belonged to a continuous effort to make sense of things for the world was full of signs; you could read your way through it.”

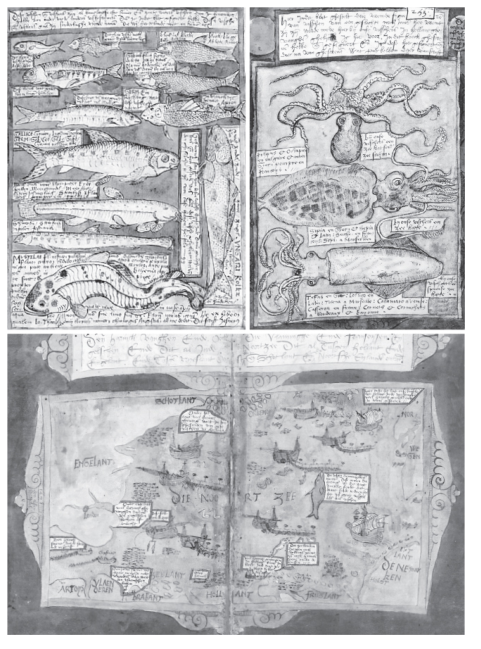

The World Ocean

Most ships did not keep a formal log till hundreds of years after the notebook’s invention.

After collecting his notes in decorative text boxes, Coenen filled the pages with sombre watercolour washes, against which framed panels of text and pictures stand out, sometimes carrying his name and monogram.

Francis Bacon had no fewer than 28 notebooks in use at once.

It is a strange thing, that in sea voyages, where this is nothing to be seen, but the sky and sea, men should make diaries; but in land-travel, wherein so much is to be observed, for the most part they omit it; as if chance we fitter to be registered, than observation. Let diaries, therefore, be brought in use.

Young Isaac Newton’s notebook Wastebook

He started writing into it from both ends at once, flipping it as he did so, so the second half of the book appears upside down. A common practice of the time, Newton uses it to separate practical ideas from a collection of linguistic titbits.

His art notes “To shaddow sweetly & rowndly withall is a far greater cunning than to shaddow hard & darke; for it best to shaddow as if it were not shaddowed’”

He’s a moment where is has information on how to make birds drunk

‘To make birds drunk,’ he notes, as if this was the most normal pastime, ‘Take such meat as they love as wheat, barley &c. steepe it in lees of wine or in the juice of Hemlock, & sprincle it wher birds use to haunt.’

Naturalist Notebook

The study of the natural world remained a constant through the classical and medieval periods, when any decent library possessed an illuminated herbarium and a bestiary, the former usually more grounded in reality than the latter. But botany and zoology moved up a gear during the late Renaissance, then further again during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. At each point, the notebook revealed new uses which helped naturalists make new observations and new deductions.

Conrad Gessner’s Historia plantarum, the best way to observe something is to draw it - beside each image sit notes on the specimen’s habitat, behaviour and abundance.

Book of daily sins:

In the seventh century, Saint John Climacus reported visiting a monastery near Gaza where every brother carried a small wax tablet on his belt. If one found himself committing (or considering) a sin, he would note it on the tablet, and at the end of the day confess it to the abbot, and the tablet would be wiped clean, literally and metaphorically.

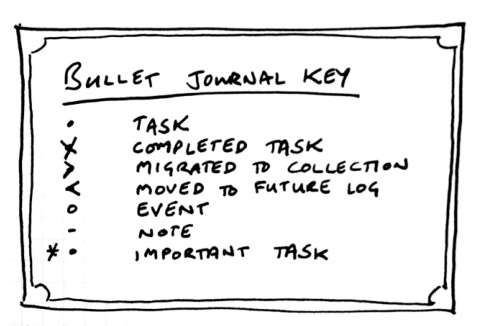

Bullet Journaling - Brooklyn 2010

Ryder Carroll began looking for a simple method of personal organization in college in the late 1990s. Diagnosed with attention deficit disorder as a child, he wanted a system to help “move past his learning disabilities.” By the time he graduated from college, he had devised the bullet journal method. A friend encouraged him to share his method, and he began sharing it online in 2013. It attracted attention on social media, earning $80,000 in Kickstarter funding to create a centralized online community of users. It was the subject of over 3 million Instagram posts by December 2018.

His success, and launch of product sparked a crisis

His success, and launch of product sparked a crisis

Deep confusion and frustration set in. On paper, I had accomplished everything that I was told would make me happy. I sacrificed a lot getting to this point, but now I was here, it didn’t seem to matter.

My entire life I thought, once I get organized and productive I’ll be happy, everything will be fine. But then I noticed that it didn’t make me any happier. I launched this company that required tens of thousands of actions, and none of those things ended up mattering.

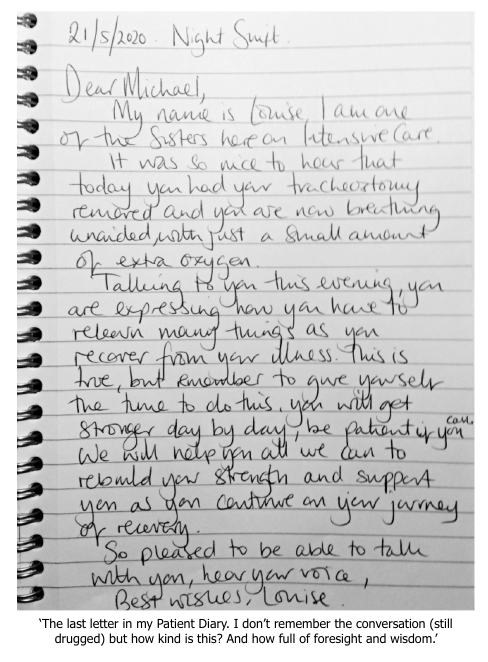

In Search of Lost Time (Patient Diaries)

Almost as disquieting is the rupture in time that ICU patients cannot avoid, particularly if they are admitted while unconscious or unaware. An accident victim may wake up with no idea of where they are, having permanently ‘lost’ weeks of their life. Referring to this blank space, Rosen would later write in a poem of ‘a matter of regret / that I’ve lost track of something’.

In the 1970s nurses realized patients needed to recover from intensive care, as well as in it. They kept diaries to make sense of the patient experiences. Each day, a nurse writes an informal diary telling the patient what they’d done, what had been done to them, and how they are.

You are in a deep sleep, but when we bathe you we see that you can react. You try to open your eyes… It is hard to tell if you will later be able to recall any of this, but we talk to you and explain what we are doing, even if you cannot respond.

When patients recover, they are given the diary to take away, and with that they can piece together fragmented memories, explain the changes to their body and reconstruct.

Another Swedish practitioner poetically defined the aim of the exercise: Att ge tillbaka förlorad tid – ‘to give back lost time’.

The diary can become a vital part of psychological recovery. Numerous studies of the Scandinavian experience testified to its effectiveness in recovering the patient’s quality of life, especially in preventing the onset of depression

“The notes are like stepping stones. They are rocks in the bog.”

Some 42 per cent of the patients with whom Rosen shared the ward died. But even in those cases their diaries have value, as bereaved relatives appreciate them as much as survivors do. It comforts them to read of the care that their loved ones received, and if they too are able to write in the diary, it gives them a safe space in which to express their own feelings. ‘Some relatives write such poignant goodbyes’, says Jones, ‘that it brings tears to my eyes.’ She knows of relatives who have placed the diary in its owner’s coffin.