created, & modified, =this.modified

Why I’m reading

I’ve read this book a few times but never took notes.

My initial interest in this subject was because while exploring I would see this distinctive, almost cartoonish symbol across multiple gravestones of a certain era. With some research I discovered it was called a soul effigy.

The thing I like about gravestone art is that it is directly related to life and death, and so over time tells of how we change our perception of this period (even the change in language from graveyard → cemetery, or various motifs ranging from skull and bones to more euphemistic, secular elements like a willow).

Further, it is somewhat neglected and hidden in plains sight. Especially in the past, they were the result of a diffusion of ideas and the themes of the artisans who created them.

Also, when walking a cemetery since it holds multiple generations, you basically can see the progression over time as you walk through it – from varying materials and design elements.

Motifs and dating

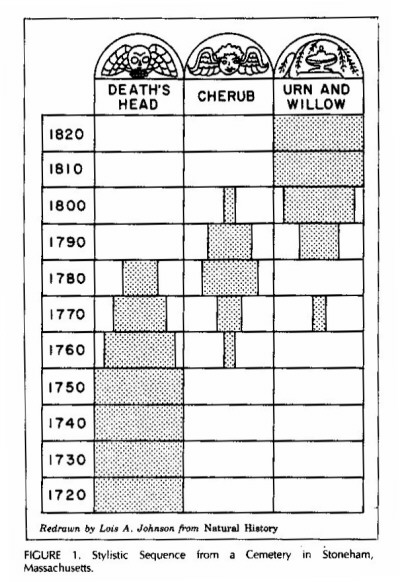

Death’s-head Motif c. 1680-1790 The death’s-head was in use from c. 1680-1790, during which time the Puritan church was dominant in New England. The death’s-head motif can be described as an “earthy and neutral symbol, serving as a graphic reminder of death and resurrection.” When looking at the epitaphs on the gravestones in conjunction Vith the symbology of the death’s-head, there is a focus on the mortality of man.

Cherub motif, c. 1760-1810 The cherub came about during the religious revival movement known as the Great Awakening. During this time, the cherub, which the Puritan’s feared could lead to idolatry because it portrayed a heavenly being, grew in popularity and acceptance. This shift can be to a shift in religious thought towards allowing the individual to have personal involvement with the supernatural. The epitaphs at the time are indicative of the belief that the soul left the body at the time of death. No longer did they say “Here lies…” but instead they specified that it was only the body which remained, “here lies buried the body…” It can be argued that the cherub motif is symbolic of a focus on the immortal component of death.

Urn-and-willow motif, c. 1760-1830 The urn-and-willow motif goes hand-in-hand with a shift from rounded to square shoulders on the gravestones. These gravestones often marked cenotaphs. The stylistic shift in design represents a shift from the graphic representation of the mortal or immortal component of an individual to a symbolic commemoration. Epitaphs on urn- and-willow gravestones often recognize achievements.

The popularity of death and afterlife as graphic subjects was due to not only the influence of Christian beliefs but the precarious nature of human existence. In art, the effect of the plague increased fascination with death. Striking depictions such as “The Dance of Death”, and woodcuts of death carrying away all members of classes became popular motifs.

The obsession with the more revolting aspects receded once the plague period diminished.

At the time of the first large scale migrations to the New World (1620-1660) there was no widespread method of grave identification. With the exception of the nobility and gentry. English graves were identified with a wooden marker, two posts and a plank fit between them.

Early American gravestones came almost exclusively from New England. The majority of the early inhabitants of LI were Puritans. Calvinism stressed the awful power of God and the helplessness of man who had been destined before time to a fate of salvation or damnation. The most widespread symbol of this time was the death’s head, symbol of mortality and the winged soul effigy, symbol of resurrection.

At this time people lived in close communion with one another, and social bonds were tighter so the death of one individual had a great effect on the whole community. Cemeteries were not located away from populated areas, as is the custom today, but centrally located, with the exception of family plots on farms.

Thought

Considering the extent this was later a matter of practicality, since a lot of cemeteries I know of are massive, park-sized.

I suppose though, once a cemetery is in place, it is fixed. It’s not a simple matter of relocation of a building, because of the all of the earth that would need to be moved (if this mass exhumation is even legal, I doubt it.)

Cases of this could be intriguing to look for, along with the historical progression (development) of sites adjacent to grave sites.

Gloves were sent as invitations to funerals. In addition, funeral rings embossed with mortality symbols and the names of the deceased were often given the friends or family members.

The gravestone price varied depending on size and quality. A few stones provide record of cost, Lydia Benitt’s stone (1791, Columbia Connecticut) has a stonecutters fee cut in large letters below the inscription.

Types of Markets

- Tomb – a rectangular brick vault, capped by sandstone or slate slab. They are less common, as they were costly and only affordable to the highest in rank and status.

- Table Stone – called as the design resembles a table. It has several vertical columns, capped by a slab placed over a grave.

- Grave Slabs or slab stones – Large slabs which entirely cover the grave.

- Headstones, often paired with a plainer footstone – most popular.

The most common shape for the headstones was the tripartite or three-lobed design. It is possible the design was meant to represent a doorway, as a symbolic representation of the intermediate position between this world and the next. It was also suggested the head and foot resembled a bed, the grave a place of rest.

Attempts to identify stonecutters by tracing stylistic progressions is complicated, since there was the practice of stockpiling stones with symbols completed but the inscriptions left blank. Few of the cutters had artistic pretensions, and it was obvious to the cutter and customer what the symbols meant – with no need to discuss.

Materials

The most common were slate and sandstone. Slate varied from near black to greenish, with light blue-grey shade predominating. Sandstone was easier to cut and led to bolder carving. Sandstone of lesser quality ages poorly, but slate can deteriorate by moss and lichen.

Other stone material such as granite and schist was sometimes used. Also local found field stones. Marble ages poorly, and are often obliterated.

Symbols

The death’s head symbolized the transitory nature of earthly existence and the fleetness which death overtakes us all.

Inscriptions on stones

Death is the wages due to Sin Through Christ eternal life we win

The clear delits wee here enjoy we fondly call our own But short favouer boured now to be repaid on

Her thread was short, her glass Her sorrow o’er, her joy soon run

This Life is a Dream and an empty sho Into the Wide World we must go

Behold and see as you pass by As you are now so once was I As I am now so you must be Prepare for Death and follow me

Thought

The Soul Effigy were frequently called angels or cherubs and the stonecutters would see little difference between the glorified soul of the just and an angel. The face was meant to resemble a soul in heaven.

Her soul has now taken flight To mansions of glory above To mingle with angels of light and dwell in his kingdom of love.

Flowers are ancient symbols of regeneration and rebirth. Other symbols seen are Crowns of Righteousness (often worn by the effigy), Shells, Pinwheels and Rosettes, Sun, Moons and Stars.

The occasional rare stone will feature a portrait. These can appear like a wingless effigy.