created 2025-04-07, & modified, =this.modified

tags:y2025computersnexusaggregatorlibrarybooks

rel: Quipu Ada Lovelace Letters Jacquard’s Web Radical Fiber - Threads Connecting Art and Science Manicule, Body in Books and Analysis of Love Library Scholars

NOTE

I’ve this research scattered all over. It is hard to give it a name. The idea is roughly exploring a connection with text, computation, weaving, body etc.

I’ll connect all points of this idea here.

Text(n.)

late 14c., “the wording of anything written,” from Old French texte, Old North French tixte “text, book; Gospels” (12c.), from Medieval Latin textus “the Scriptures; a text, a treatise,” earlier, in Late Latin “written account, content, characters used in a document,” from Latin textus “style or texture of a work,” etymologically “thing woven,” from past-participle stem of texere “to weave, to join, fit together, braid, interweave, construct, fabricate, build” (from PIE root teks- “to weave, to fabricate, to make; make wicker or wattle framework”).

Context = con-textere → contexus, together + to weave.

The meaning “a digital text message” is by 2005.

To Socrates, a word (the name of a thing) is “an instrument of teaching and of separating reality, as a shuttle is an instrument of separating the web”

Text isn’t far off from being woven - especially historically where the text is copied in manuscripts, or combined from varying sources (even in final works, without sophistications).

Words Also alternative uses here,

- sophistication - the process of making a book complete by replacing missing leaves with leaves from another copy.

- gloss - like glossary, a translation of word or phrase. An explanation, interpretation or paraphrase. Glossa originally meant an unusual word, but later referred to the definition penned above it in minuscule writing. From collections and definitions of glossae we acquired glossary.

rel:Anathema! Medieval Scribes and the History of Book Curses by Marc Drogin - adversaria- commentaries or notes (as on a text or document) or a collection of notes, remarks, or selections commonplace book.

- exemplar - master copy from which other copies were made. (exemplary)

We may say most aptly that the Analytical Engine weaves algebraical patterns just as the Jacquard loom weaves flowers and leaves.

Early Computer Terms

The store and the mill: the terminology was an elegant metaphor from the textile industry, where yarns were brought from the store to the mill where they were woven into fabric, which was then sent back to the store. In the Analytical engine, numbers would be brought to the store from the arithmetic mill for processing, and the results of the computation returned to the store.

String

The use of the word “string” to mean things arranged in a line, series or succession goes back centuries. In 19th century typesetting, compositors used the term “string” to denote the default length of type on paper – string would be measured to determine the pay.

From the referenced dictionary entry (The Oxford English Dictionary. Vol. X. 1933.)

C.I. Lewis in 1918:

A mathematical system is any set of strings of recognisable marks in which some of the strings are taken initially and the remainder derived from these by operations performed according to rules which are independent of any meaning assigned to the marks. That a system should consist of ‘marks’ instead of sounds or odours is immaterial.

Page

One side of a leaf. The front side of a leaf is called the recto or obverse and the back side of the leaf is called the verso or the reverse.

The word “page” comes from the Latin term pagina, which means, “a written page, leaf, sheet”, which in turn comes from an earlier meaning “to create a row of vines that form a rectangle”. The Latin word pagina derives from the verb pangere, which means to stake out boundaries when planting vineyards.

Folio

From Middle English folio (“leaf of a book”), borrowed from Medieval Latin foliō, Late Latin foliō, Latin foliō, the ablative singular form of Late Latin folium (“leaf or sheet of paper”), Latin folium (“leaf of a plant”), ultimately from Proto-Indo-European *bʰleh₃- (“bloom, flower”). Doublet of foil and folium, and distantly related to phyllo and phyllon.

Vox - Ars grammatica*

Every vox (voice/word) is either articulate or confused. If articulate, it can be captured in letters. Confused sounds cannot be written.

“The principal members of the human body are called artus and the smaller articuli. Anything that can be grasped by these writing articuli is itself an articular vox.”

Letters join the voice with page and hand; like the hand, they too can be understood as articulate bodies.

And sometimes also the very work done by someone’s hand is called their hand; as one is said to recognize a hand when they recognize what some-one has written. - Augustine, In Iohannis euangelium

Literalis vox - scriptible language, is called articulate because it is subject to joints, that is, fingers that write.

The reader must first analyze— that is, etymologically, untie— the individual words from the line of letters and collect them anew into a signifying whole.

Servius explains in his commentary on Donatus, “What ever is read is vox articulata. If you unravel that which is joined together in reading, you produce discourse”

From Remember The Hand by Catherine Brown Writing extends one line and then goes back to spool out another; reading loosens, then reweaves, the net. This recursive flirtation with erasure is an essential characteristic of the grammarians’ understanding of lettered practice. It is etymologically (and thus, for the Isidorean Middle Ages, ontologically) built into letters themselves, according to Priscian and everyone who quotes him in the Middle Ages. The letter, they say, “is called littera either as a legitera (‘reading- road’), because it provides a path for reading, or derived from litura (erasure), as some prefer, because the ancients used to write mostly on wax tablets”

Colophon Poem

Oh you alertly sitting, behold the face of the page. And here are my two tired limbs With all my goods mixed in, I am joined to this.

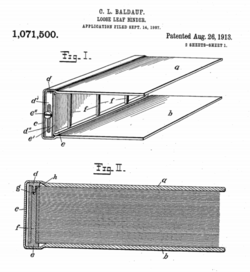

Nelson’s Perpetual Loose Leaf Encyclopedia

NOTE

Kind of early webpage with continuous updates.

Nelson’s Perpetual Loose Leaf Encyclopaedia: An International Work of Reference was an encyclopedia originally published in twelve volumes by Thomas Nelson and Sons starting with Volume 1 in 1906 through to Volume 12 in 1907. It was published in loose leaf format; subscribers received updates every six months.

… the book that literally never does grow old, that has a concise, authoritative statement on the memorable event of yesterday as well as on the event that occurred thousands of years ago; the book that is never finished, and that nevertheless has the latest word on pretty much any subject regarding which immediate information is desired, seems very much like the wild and insubstantial dream of some overworked press agent, were it not that the thing has actually been accomplished, that the book in question really does exist

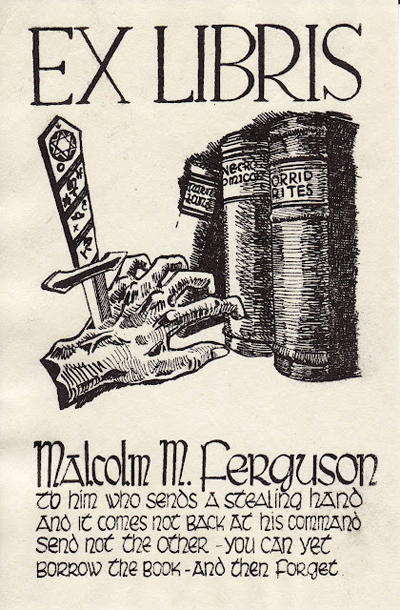

Anathema

Another word sense, noted in Marginalia of a literary curse inscribed upon books. The shunned modification, theft, and being lost.

rel:Library Scholars

TO Stephen Dance this booke belong and he that steale it dowth him rong lev it alone and pase there by, in every place where it doth lie

klaxon here for lines below to hasten scroll and shun ye slowe pass along avert thine eye for spring latent errors when he modifye

If anyone take away this book, let him die the death; let him be fried in a pan; let the falling sickness and fever seize him; let him be broken on the wheel, and hanged. Amen.

To him who sends a stealing hand and it comes not back at his command send not other - you can yet borrow the book - and then forget

Steal not this book my honest friend for fear the gallows should be your end and when you die the lord will say and where’s the book you stole away?

Book Curse

A book curse was a widely employed method of discouraging the theft of manuscripts during the medieval period in Europe. The use of book curses dates back much further, to pre-Christian times, when the wrath of gods was invoked to protect books and scrolls.

The earliest known book curse can be traced to the king of Assyria in 668 to 627BC, who cursed had a curse written on the tablets collected at the library of Ninevah, considered to be the earliest example of a systematically collected library.

I have transcribed upon tablets the noble products of the work of the scribe which none of the kings who have gone before me had learned, together with the wisdom of Nabu insofar as it existeth in writing. I have arranged them in classes, I have revised them and I have placed them in my palace, that I, even I, the ruler who knoweth the light of Ashur, the king of the gods, may read them. Whosoever shall carry off this tablet, or shall inscribe his name on it, side by side with mine own, may Ashur and Belit overthrow him in wrath and anger, and may they destroy his name and posterity in the land.

He who breaks this tablet or puts it in water or rubs it until you cannot recognize it and cannot make it to be understood, may Ashur, Sin, Shamash, Adad and Ishtar, Bel, Nergal, Ishtar of Nineveh, Ishtar of Arbela, Ishtar of Bit Kidmurri, the gods of heaven and earth and the gods of Assyria, may all these curse him with a curse that cannot be relieved, terrible and merciless, as long as he lives, may they let his name, his seed, be carried off from the land, may they put his flesh in a dog’s mouth.

At the time, these curses provided a significant social and religious penalty for those who would steal or deface books, which were all considered to be precious works before the advent of the printing press.

Books were scarce and valuable. They conferred prestige on the monastery that possessed them, and the monks were not inclined to let them out of their sight. On occasion monasteries tried to secure their possession by freighting their precious manuscripts with curses.

Sophistication

Sophistication has ties to Survey of Being Lost and Survey of Vandal, Fake and Replica.

In some cases this is done with the intent to deceive or mislead, modifying and offering books for sale in an attempt to sell them for a higher value. When offered for sale, a book’s description should be clear and unambiguous, and indicate exactly and in detail any changes that have been made to the book.

“This adjective, as applied to a book, is simply a polite synonym for doctored or faked-up. It would be equally appropriate to a second edition in which a first-edition title-leaf had been inserted, to another from which the words second edition had been carefully erased, to a first edition re-cased in second-edition covers, to a copy whose half-title had been supplied from another copy (made-up) or another edition, or was in facsimile.”

Etymology

The term “sophisticate” originates from Ancient Greek, a verb meaning to become wise or learned. It later acquired the negative connotation of Plato’s critique of the Sophists, for deceptive reasoning and rhetoric. The term’s earliest appearances in late medieval and early modern England use “sophisticated” in this negative sense of adulterating or mixing in impure or foreign elements. This meaning is similar to the term’s 20th century application to rare books.

History

The practices involved in the sophistication of books have not always been viewed negatively by book-buyers and book-sellers

In 1798, a book was considered to be complete if all the information it was expected to contain was present. When John Philip Kemble described one of his books as “perfect”, he meant that all of its textual content, including illustrations, dedications and other information, was included in the copy. He did not mean that the book was in the same condition in which it originally left the printer.

Victorian and Edwardian collectors, the goal was a complete aesthetic object and the sense of the content. Replacement, and origins weren’t a concern.

Changes in binding techniques and methods of paper restoration made it possible to remove stains, fill in lost pages, and rebuild leaf margins almost invisibly. These rebound and “made-up” books were not seen as problematic at that time, and were often prized by both collectors and booksellers.

It was complete in the sense that it contained all the necessary information for detecting imperfect copies.

NOTE

This shift is fascinating to me.

With this shift in perspective on the perfect book, from complete content to exemplary copy, modifications that were seen as acceptable in earlier centuries were often seen as “tainting” the structure of the book. Sophistication became less acceptable. In mid-later 20th-century usage, the term is often put in negative contrast to the preservation of the material integrity of an original work.

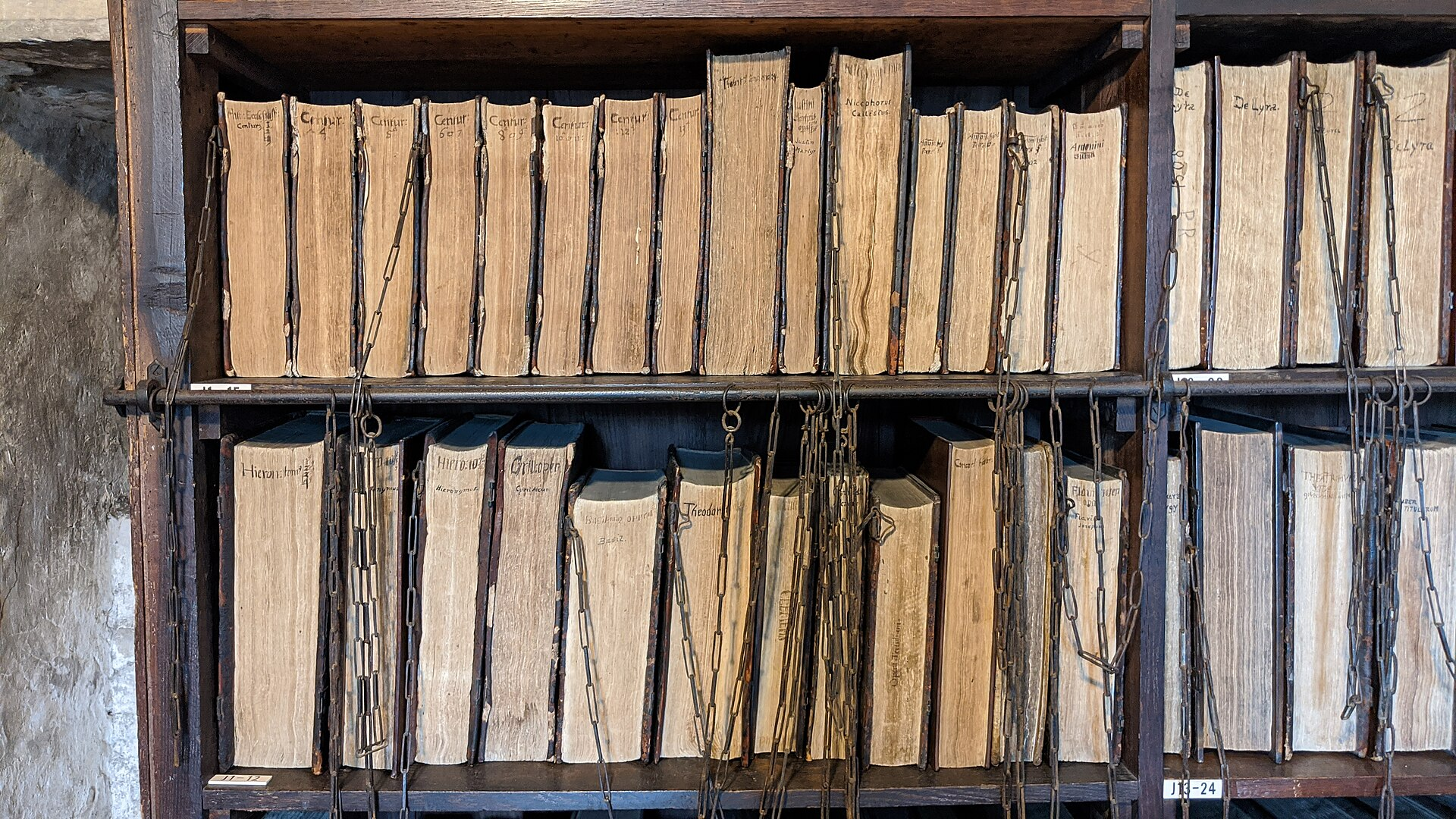

Text Literary Theory

The word text has its origins in Quintilian’s Institutio Oratoria, with the statement that “after you have chosen your words, they must be weaved together into a fine and delicate fabric”, with the Latin for fabric being textum.

African Folklore

African Folklore - Text and Textile

created 2025-04-24, & modified,

=this.modified

rel:QuipuThought

This is an excerpt from a book, African Folklore - An Encyclopedia — Philip M Peek & Kwesi Yankah that I sought out after finding a reference in Book of Symbols - Reflections of Archetypal Images.

It’s too involved and lengthy for a full read for me but I can find Survey of Text Etymology, Connections to Fiber, Body information for the citation.

Textile Arts and Communication

In African societies, where oral traditions take precedence over written ones, visual arts play a vital role in their functions as language.

The cloth lends itself to this function

- cloth is inherently a flat surface

- symbols can be applied, operating as a page.

- it has a rich and varied syntax.

- it comes in a variety of fibers woven in any number of ways, determined by which type of loom is used.

- cloth is pliable, portable medium

Cloth and Language

Threads are interwoven to produce cloth, much like words are interconnected to create syntax.

Language involves the building of written symbols or sounds to communicate an idea. Similarly, weaving requires the gradual addition of weft-threads to the warp as the process progresses. And, just as warp threads interconnect with those of the weft, words interrelate to make up the syntax of a sentence

The Dogon of Mali are among a number of African cultures that readily acknowledge the existence of speech in cloth.

They would say that “to be nude (that is, without cloth) is to be without speech.” The Dogon word for cloth, soy, even has its roots in the word so, their word for the speech of their creator god, Nommo.

The Dogon also equate the weaving process to the nature of language, believing that the threads on their loom interconnect to produce fabric just as words are combined to make speech.

They, like many groups throughout West Africa, weave on a horizontal, foot-treadle loom that produces a long, narrow strip of cloth. The Dogon claim that speech came about through weaving on such a loom. They refer to the entire loom apparatus as so ke ru, meaning “secret speech,” and equate its individual components to the physiology of an individual’s speech mechanism. For example, the reed is equated to teeth, the shuttle to the tongue (because of its constant back-and-forth motion inside the mouth) and the heddles to the uvula that rise and fall like the words themselves. Even the creaking sound of the loom during the weaving process itself is likened to the sound of the first manifestation of the word from the creator.

Dogon cloth design generally consists of white and indigo checks, either uniform or varied in size. The color and design elements in the cloth carry or connote a specific meaning. For example, the white characterizes truth and the speech of the creator god, whereas the black refers to falsehood, obscurity, and the secret speech of male initiates. The check designs refer to the cultivated field (which resembles such a configuration), the white checks being fields on the plains (i.e., easy to cultivate), and the black ones being those of the plateau, where cultivation is difficult. In sum, cloth and its production for the Dogon is a metaphorical expression of their worldview, a view that encompasses the dichotomies of village/bush, plant/animal, daily/ritual, male/female.

Cloth as Written Text

Just as cloth is used as a kind of surrogate for speech, it functions as a surface onto which words and word-derived imagery are applied.

Islamic traditions throughout North Africa produce cloths with words encoded in them. One North African type, called tiraz, has prayers or praises to rulers woven into the cloth itself. Indeed, in some cultures, such as those of Algeria, the very name for weaver (reggam) has its roots in a word meaning to write.

Link to original

The Body in Books

- corpus

- Manicule, Body in Books and Analysis of Love

- thumb-indexes

- index

- appendix

- manuscript - handwritten, manu - by hand + scriptus - written.

- handbook/manual

- spine/back

- heading/footer

- glossary - from ancient greek glôssă - tongue, a language

- dog-eared

- tissue - thin protective sheet laid over an illustration

- DNA (not in a godly codex type of way, but maybe how we approach it symbolically/alphabetically)

- colophon - meaning finishing touch in Greek

- noduli (nodulus) – from, small legs given to the back covers of books so that the covers were kept clear of the surface (cannot find any further references, but nodulus means nodule, especially concerning the brain - a prominence on the inferior surface of the cerebellum forming the anterior end of the vermis)

- enjambment - line runover from French jambe, leg.

- holograph - the document written entirely by the person whom it precedes - from Greek written in full, written entirely by the same hand - a manuscript autograph.

Whence did the wond’rous mystics art arise Of painting SPEECH, and speaking to the eyes? That we by tracing magic lines are taught, How both to colour, and embody THOUGHT? Thomas Astle 1780

The reader must often physically block the closing of the book, by inserting their body into it. A book will often close itself otherwise.

My intuition is that a book that has a human face on the cover (not even a drawn face, but a photographic portrait) will be the one that is the focal point when browsing or at least be registered in a different way. For example, I have a book in my office Yoko Ono Music of the Mind where Yoko is featured on the cover. I must move the book so Yoko is not facing, or else the gaze becomes too noticeable.

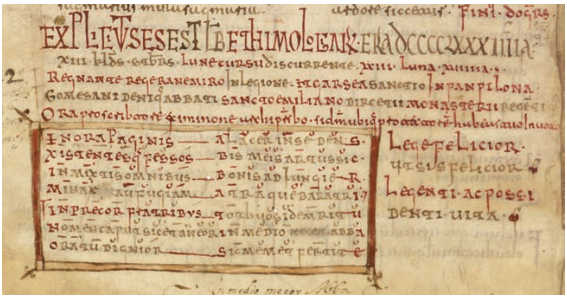

The production of the book, was a laborious task. Copier of manuscript in 945 notes:

He who knows not how to write thinks that writing is no labour, but be certain, and I assure you that it is true, it is a painful task. It extinguishes the light from the eyes, it bends the back, it crushes the viscera and the ribs, it brings forth pain to the kidneys, and weariness to the whole body. Therefore, O reader, turn ye the leaves with care, keep your fingers far from the text, for as a hail-storm devastates the fields, so does the careless reader destroy the script and the book. Know ye how sweet to the sailor is arrival at port? Even so for the copyist in tracing the last line.

An early meme appearing in scribe work, tracing back to the 3rd century B.C. (perhaps so common that it was inserted without thought)

Three fingers hold the pen but the whole body toils.

The practice of tattoo and applying text to the body.

Margins

While reading one day I was looking at the page and struck by how much of it was empty space.

Historically margins held Marginalia (though I can’t say this is the purpose, and just as characteristic of the space being available – which makes me wonder how a world lacking margins would affect notetaking.) There is an aesthetic function as well, to focus the reading and provide uniformity to the layout.

But regarding the body the margins are made for protection of the text, but also because they are space for the readers hands to grip the book without obscuring the text (so obvious, but also hidden in plain sight, the body in the book). What place does this serve in a digital book?

Thought

A book with designated places to be held on the pages, in the manner of the game Twister. A book that commands the hand to point in spaces. Zig zagging, or line tracing with a pointed finger. A page of all margins meant for freeform holding.

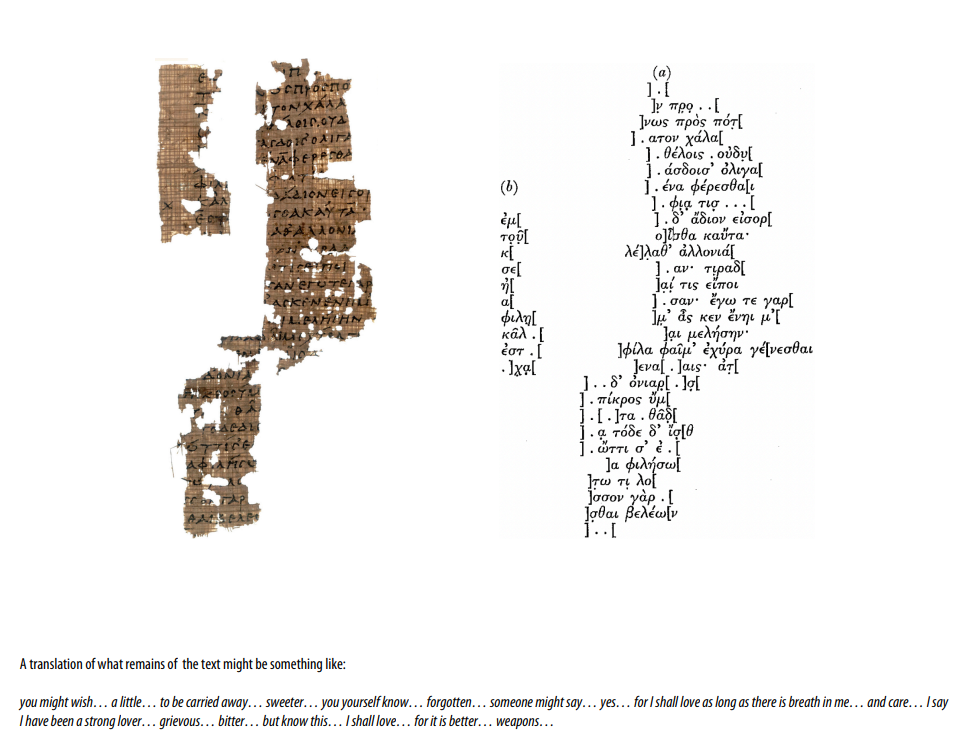

Discovering fragments of poetry, because they were bound to the body of a mummy:

On Fragments, while researching Pektis

Not enough of this poem is preserved for the reader to get an overall idea of its subject matter – not one line is complete, and not all lines contain even a single complete word -and what remains has the quality of disjunct glimpses into intimate secrets, perhaps as if intermittently overheard.

It seems like we found Sappho fragments because they were being applied to Egyptian mummies.

The poem which is now her fourth to survive had a tortuous and not unromantic discovery. It was found in the cartonnage of an Egyptian mummy, the flexible layer of fibre or papyrus which was moulded while wet into a plaster-like surface around the irregular parts of a mummified wrapped body, so that motifs could be painted on.

Link to originalThought

Musicality is accurate, reading these fragments I’m reminded of Burial lyrics or sample-based lyrics.

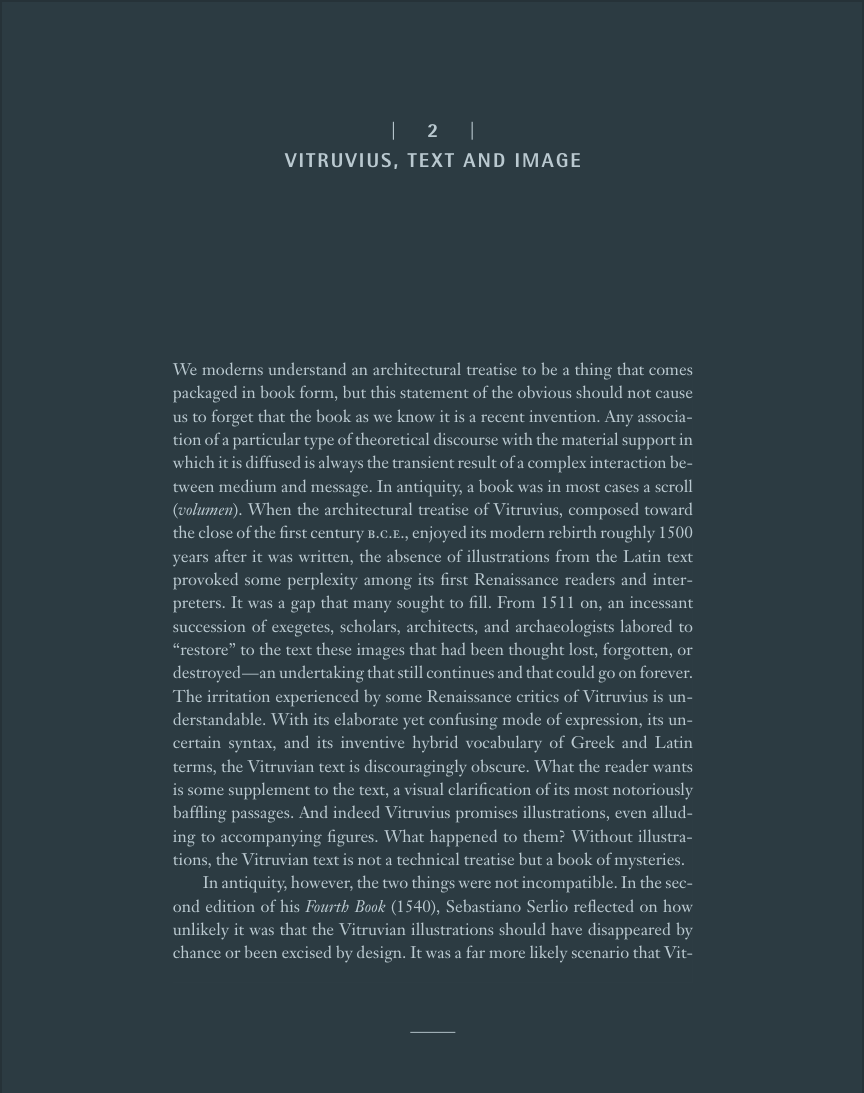

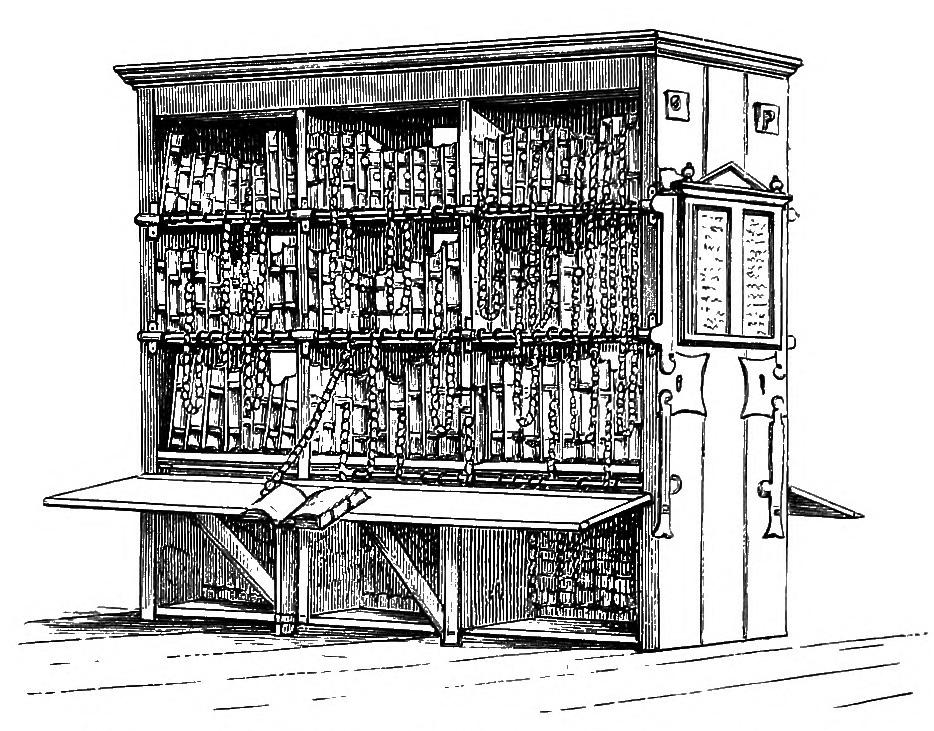

Chained Library

A chained library is a library where the books are attached to their bookcase by a chain, which is sufficiently long enough to allow the books to be taken from their shelves and read, but not removed from the library itself.

Chains were attached to the corner or cover and not the spine, to prevent strain. Books were houses with the pages visible, so the book would not require turning and thus knots. Librarians would use a key to remove the books from the collection.

In Zutphen the book is fitted with a clasp and allowed to slide along a rod they are fastened to. In Zutphen 60 keys were issued for the library (including to townsfolk), so there was an openness that made the chaining a necessity.

On Foredge shelving

This was normal practice in libraries for much of the sixteenth century for two reasons. One is that writing or printing the title and author’s name on the spine was not common until the 17th century and therefore the ‘back’ of the book was purely functional, holding the pages together. The other is that books, like the manuscripts which preceded them, were often held securely by a chain fastened to a metal staple on the fore-edge of the wooden board

In Marsh’s Library system (1701), books were not chained but readers were locked into cages to prevent rare volumes from [[ wandering.

In the Middle Ages, books were expensive and for the privileged, but they were highly valued. Books were the prime target for thieves and impoverished students to steal and sell. As a result, books were chained to shelves to preserve information.

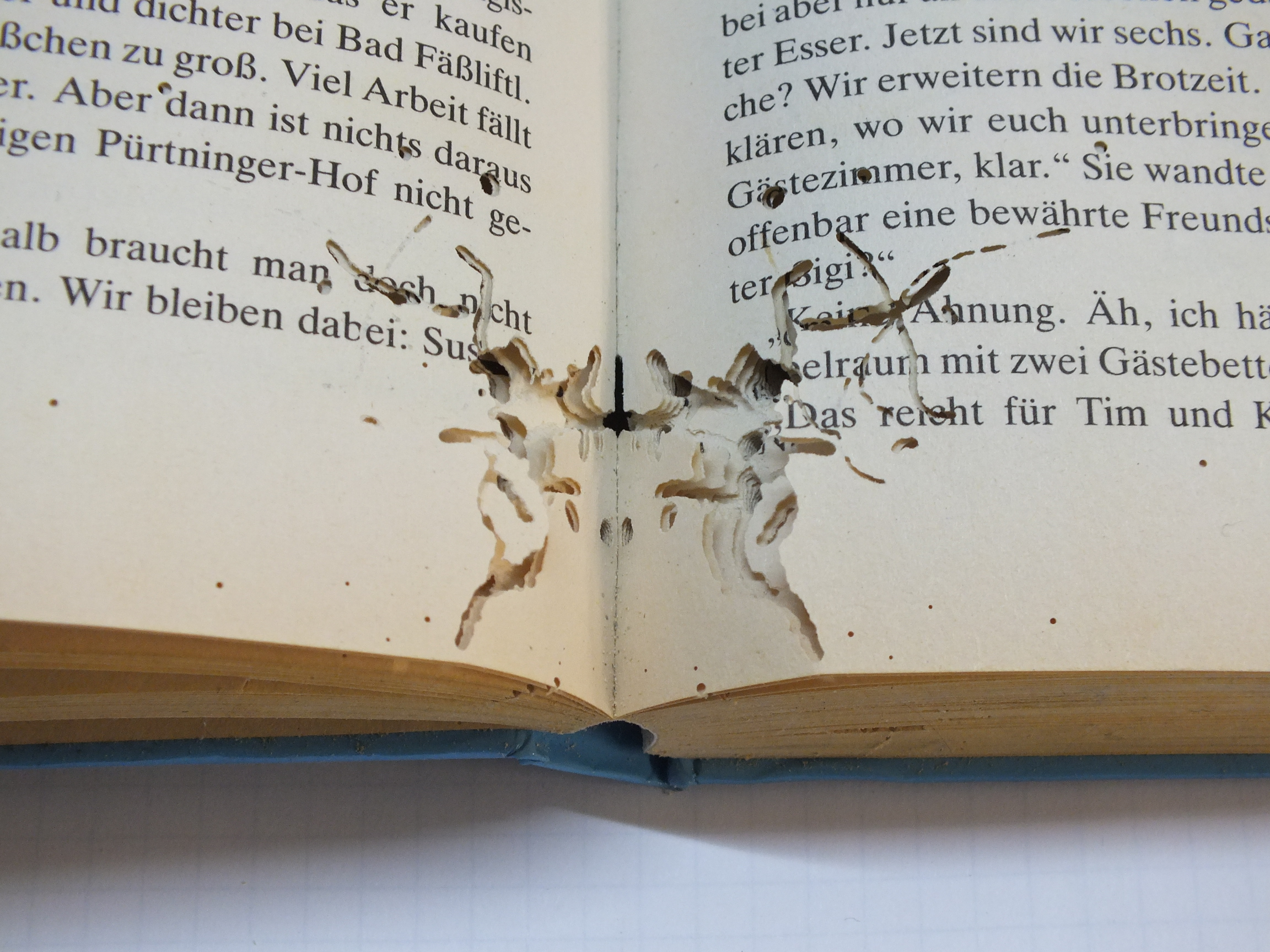

Book Worm

Bookworm is a general name for any insect that is said to bore through books.

Areas of archives, libraries, and museums that are cool, damp, dark, and generally undisturbed are common sites for such growth, generating a food source which subsequently attracts booklice. Booklice will also attack bindings, glue, and paper.

Book eating-insects

- Woodboring Beetles

- Termites

- Ants

- Moths

- Roaches

- Zygentoma (siver fish)

Line

Old English līne ‘rope, series’, probably of Germanic origin, from Latin linea (fibra) ‘flax (fiber)’, from Latin linum ‘flax’, reinforced in Middle English by Old French ligne, based on Latin linea

The word line comes from Latin linea derived from the word for a thread of linen. We can look at the lines of poetry as slender compositional units forming a weave like that of a textile. Indeed, the word text” has the same origin as the word textile.” It isn’t difficult to compare the compositional process to weaving, where thread moves from left to right, reaches the margin of the text, then shuttles back to begin the next unit

Spinning Yarn

Originally a nautical term dating from about 1800, this expression probably owes its life to the fact that it embodies a double meaning, yarn signifying both “spun fiber” and “a tale.”

Seaman often had to spend time repairing rope onboard the ship. This time-consuming task involves twisting fibers together, which is alleged to have been referred to as “spinning yarn.”

In The Romans of Partenay or of Lusignen Otherwise known as the Tale of Melusine Jean d’Arras in 1382-1394, spinning yarns or stories as told by the ladies spinning sewing machines, coudrette.

Thread

It’s possible spinning a yard was influenced by the earlier use of spinning a thread. The word thread has long been used figuratively to explain a narrative train of thought and was possibly first documented in the 1300s in Kyng Alisaunder, a medieval romance:

“He hath y-sponne a threde, / That is y-come of eovel rede.”

Computing Threads

Threads initially made an appearance under the name “tasks” in IBM batch processing operating system, OS/360.

Within the hierarchy of threads, exists the concept of fibers, or an even lighter unit of scheduling which are cooperatively scheduled. These are related to coroutines, where coroutines are a language level construct where fibers are system level.

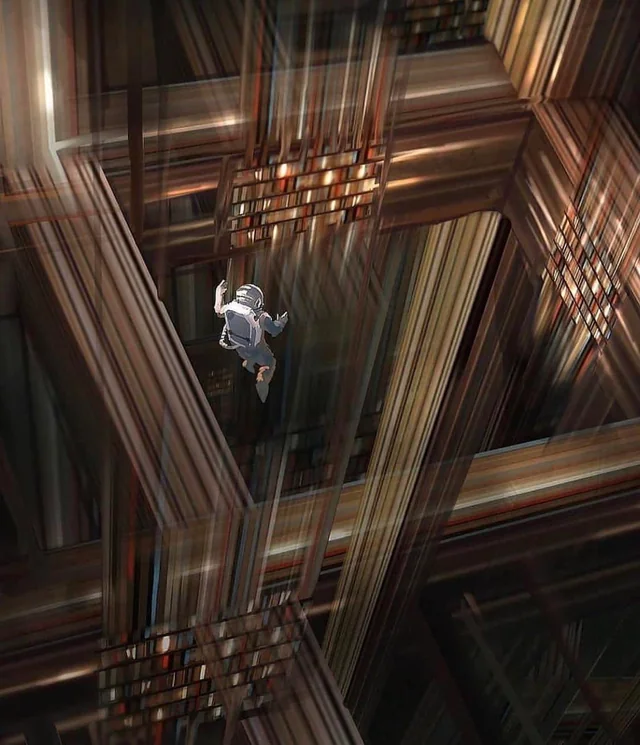

Depiction in Interstellar

The humans in the film Interstellar perceive the superdimensions as libraries with threads.

This is the Tesseract (four ray, referring to the edges). In the film,

Everything is linked by the strings of time, which Cooper can manipulate. The beings made this comprehensible to Cooper by allowing him to physically interact with the Tesseract. Every push of a book from him was communicated to the appropriate time period with gravity, and when he touches the “strings” of the watch he gave his daughter, he can cause its hand to twitch from the moment he does so for the rest of its existence in time itself.

Manuscript

Sentiments from St. Jerome, This thing I write is subtracted from my life:

Every day we die, every day we are changed, yet still we think ourselves eternal. This very thing that I am dictating, that is written down, that I reread and correct, is subtracted from my life. As many punctuation marks as my secretary makes, so many are the forfeitures of my time. We write, we write back: the letters cross the seas, and as the keel of the ship cuts furrows in one wave after another, the moments of our lives slip away.

Body as a Library

rel: A History of Reading by Alberto Manguel

The author is tutored in German, and is given poetry to memorize to improve his German pronunciation. He could not understand what use they’ll be. His tutor says, “They’ll keep you company in the days you have no books to read.” The tutor tells the story of his father, murdered in Sachsenhausen, who has been a famous scholar who knew classics by heart. During his time in the concentration camp, he has offered himself as a library to be read by his fellow inmates.

Medieval Jewish Society

rel: [A History of Reading by Alberto Manguel]

The ritual of learning to read was explicitly celebrated. On the Feat of the Shavuot when Moses received the Torah from the hands of God, the boy about to be initiated was wrapped in a prayer shawl and taken by his father to the teacher. The teacher sat the boy on his lap, and showed him a slate on which were written the Hebrew alphabet, a passage from the scriptures and the words “May the Torah be your occupation.” The teacher read out each word and the child repeated it.

Then the slate was covered with honey, and the child licked it, thereby bodily assimilating the holy words. Also, biblical verses were written on peeled hard-boiled eggs, and on honey cakes which the child would eat after reading the verse out loud to the teacher.

Lapiz Lazuli

Scribes, and textual work was once thought to be the exclusive profession of men. They found women scribes through examination of teeth.

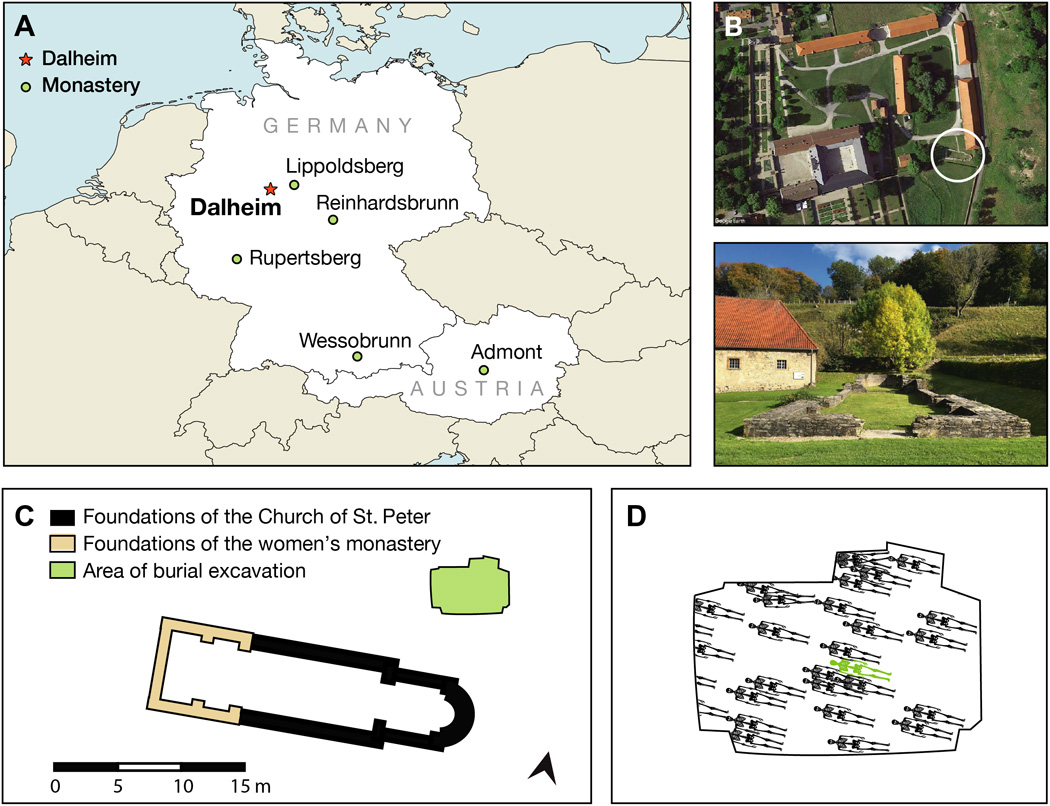

There is also evidence that women scribes, in religious or secular contexts, produced texts in the medieval period. Archaeologists identified lapis lazuli, a pigment used in the decoration of medieval illuminated manuscripts, embedded in the dental calculus of remains found in a religious women’s community in Germany, which dated to the 11th-12th centuries.

Thought

This is fascinating as well. A middle aged woman is found buried in a cemetery, with a “rare and expensive mineral pigment in her dental calculus.”

The authors propose four theories

she was a scribe or book painter involved with illuminated manuscripts.

she was employed in the production of artistic materials

she consumed lapis lazuli in the context of Lapidary Medicine, Lapidaries

performed emotive devotional osculation of illuminated books produced by others (that is, she kissed them).

In Germany, women’s monastic communities, especially during earlier periods, were largely made up of noble or aristocratic women. Many were highly educated, and devotional reading was encouraged as an expression of piety. These women would have led lives largely free of hard labor, consistent with the absence of occupational skeletal stress observed for B78. Work was encouraged within the monastery, however, and activities related to book production were considered worthy pursuits. In adding detail to their illuminations, it is plausible to assume that artists would have occasionally licked their brushes to make a fine point, a practice that later artist manuals refer to explicitly. In doing so, pigments, such as lapis lazuli, may have been introduced into the oral cavity, where they could have become entrapped within dental calculus. The repeated activity of inserting the tip of the brush into the mouth could explain the distribution pattern of in situ blue particles observed across multiple calculus fragments.

Kissing in Prayer Books (Ritual Osculation)

Ritual osculation (kissing) of painted figures in illuminated prayer books became more common. In response, illuminators began adding decorative “osculation tablets” to these books to deflect kissing away from the painted figures, which suffered damage—including paint removal—through repeated kissing.

No books survive from the monastery, either from its libraries or in any other surviving works. Nearly invisible in the historical record, the women of Dalheim are known to us today nearly exclusively through the archaeological record and a handful of brief textual references

In Remember The Hand by Catherine Brown

Eighth-century Iberian theologian Beatus of Liébana: The person who reads Scripture frequently (knows that) the letter is the body. But there is a spirit in the letter. This letter has a spirit, that is, a meaning. But no one can understand this meaning without the letter, that is, without the body.

English sentence is “I read a book” - the book is a passive recipient of the reader’s action. In ancient medieval practice, the activity went both ways:

We should read none save the best authors and such as are least likely to betray our trust in them, while our reading must be almost as thorough as if we were participating in the writing.

When Florentius imagines us reading in this codex, he understands the book as exactly this sort of gathering place. This is a place where reading is not an action performed upon a text, but rather an encounter in which both participants act upon each other and are changed as a result. The page might gain new marks upon its surface: pointing fin gers, pen-trials, doodles, sweat. And what St. Paul calls “the fleshly tables of the heart” (tabulis cordis carnalibus) (2 Cor 3:3), inscribed by reading, become themselves living copies of the book.

Of making many books there is no end: and much study is an affliction of the flesh. – Eccles. 12:12

Chirograph

created 2025-05-10, & modified,

=this.modified

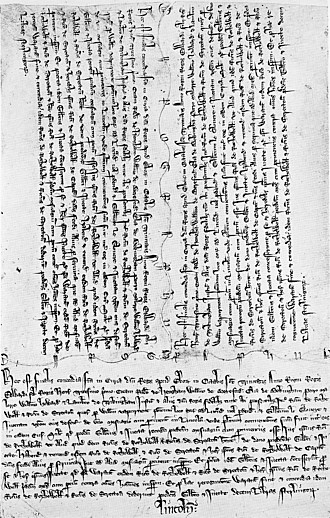

rel:Three, Rule of three Survey of Text Etymology, Connections to Fiber, BodyA chirograph is a medieval document, which has been written in duplicate, triplicate or very occasionally quadruplicate (four copies) on a single piece of parchment, with the Latin word chirographum (occasionally replaced by some other term) written across the middle, and then cut through to separate the parts.

Link to originalThe practice of separating the copies with an irregular cut also gave rise to the description of the documents as “indentures”, since the edges would be said to be “indented”

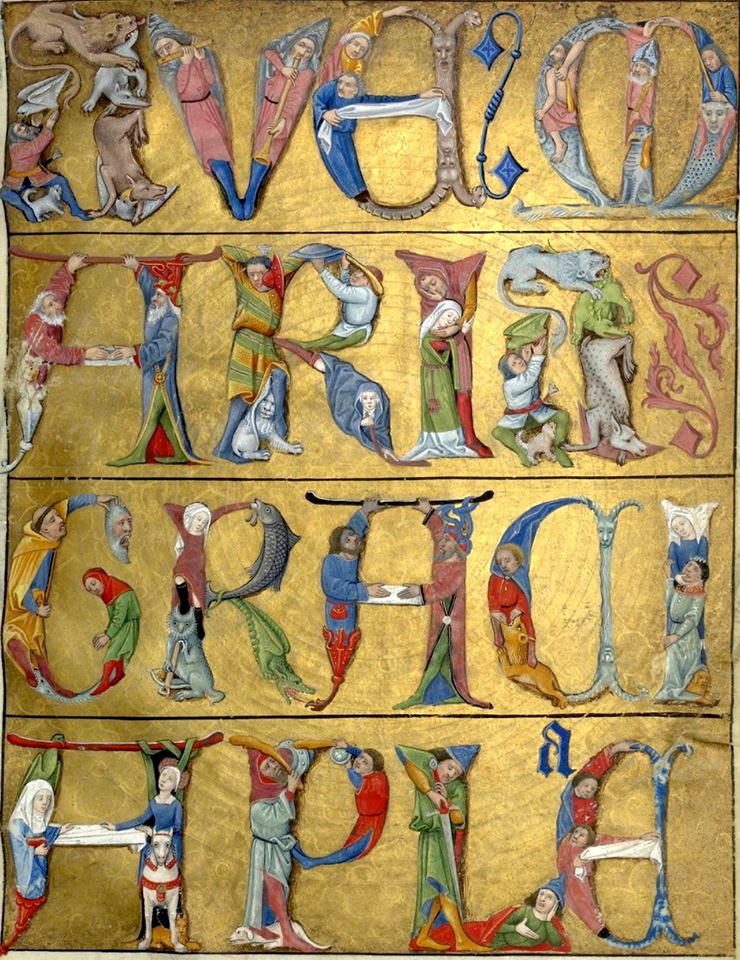

Ave Maria Gratia Plena

Heure de Charles d’Angoulême. Horae ad usum Parisiensem. Latin 1173. 1485. In view 113 - Folio 52r you see bodies in contrasting arrangements, shaped to letters.

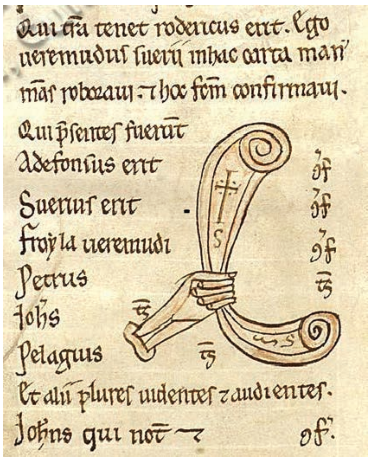

Signum Manus

rel:Manicule, Body in Books and Analysis of Love

Sign of the Hand.

As a matter of authority of a text, a symbolic representation of the hand was presented on the page of scribes. The sign can be letters, fully symbolic, or can take the literal hand .

Scribe Chewing

The reed was the customary Egyptian writing instrument. The scribe would chew one end of reed to create a brush-like instrument. The body is found here too, where the deformation was done with the mouth, then imparted upon the papyrus.

Ink in the ancient world was allowed to dry after production and then stored and carried in solid form, like watercolor tablets of today.

Cangjie and the Advent of Chinese Writing

Cangjie is thought to have once been an historian to Huangdi. As the court historian and record keeper, he was asked by the Yellow Emperor to devise a method for recording important information. Legend has it that Cangjie journeyed into the wilderness to clear his mind before embarking on his monumental task. During his sojourn into nature, he saw natural patterns in objects like trees, animals, stars, planets, and buildings. He translated the patterns he saw into logograms which would become the writing system used all across the Chinese speaking world.

Another version of the story states that Cangjie was inspired after observing the lines on a tortoise’s shell. After he invented the writing system, grain such as millet rained down from heaven and demons and ghosts wailed at night.

The name Cangjie, is still used denoting the Cangjie input method (cj) of typing, which was the first system of entering Chinese input using a standard QWERTY-style keyboard.

The keys are placed in four groups one being

Body-Related Group — corresponds to the letters ‘O’ to ‘R’ and represents various parts of the human anatomy – person, heart, hand, mouth.

Book Rights in Antiquity

The authors of antiquity had no rights concerning their published works; there were neither authors’ nor publishing rights. Anyone could have a text recopied, and even alter its contents. Scribes earned money and authors earned mostly glory unless a patron provided cash; a book made its author famous. This followed the traditional concept of the culture: an author stuck to several models, which he imitated and attempted to improve. The status of the author was not regarded as absolutely personal

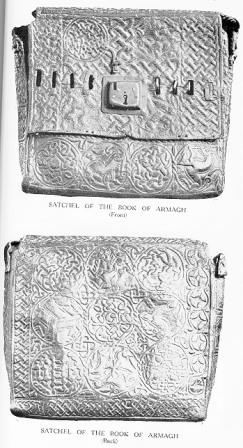

Book Satchel - Polaires

The book satchel or polairie is a limp bag, or wallet style bag in which religious text were stored. The satchel was either hung on a peg in the library when not in use or carried around the neck while traveling; it also made the books easier to carry out of the monastery if there was a fire or a raid (Waterer 76, 78). The unique thing about these items and their use is that the practice of making and using these “book bags” seems to be solely the trade of Irish monks during the medieval period. Almost all the images of Irish saints, clerics, etc. have them carrying a satchel

There are only three physical examples of polairies in existence today, The Book of Armagh polairie 11th or 12th century, the Breac Moedoic budget 8th or 9th century, and the Corpus Christi budget 8th or 9th century (Waterer 76-80). Although the Breac Moedoic budget is not a polairie per say (it actually contains a metal shrine, and therefore should be classified as a Cumbach or reliquary) the design and construction of the budget is the same as the others and therefore added to the list of existing polairies.

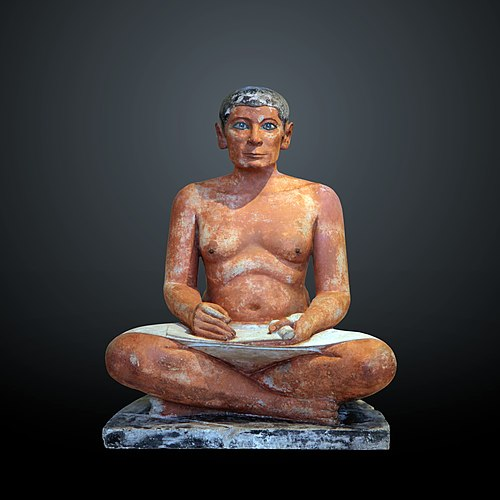

The Seated Scribe

rel: The Rise and Fall of Alexandria by Pollard and Reid

A famous piece of ancient Egyptian art, depicting a seated scribe at work.

From either the 5th Dynasty, c. 2450–2325 BCE or the 4th Dynasty, 2620–2500 BCE

I love that the reed pen is missing from the figure, but his hands continue to be eternally in the position to write.

It is a painted limestone statue, the eyes inlaid with rock crystal, magnesite (magnesium carbonate), copper-arsenic alloy, and nipples made of wood.

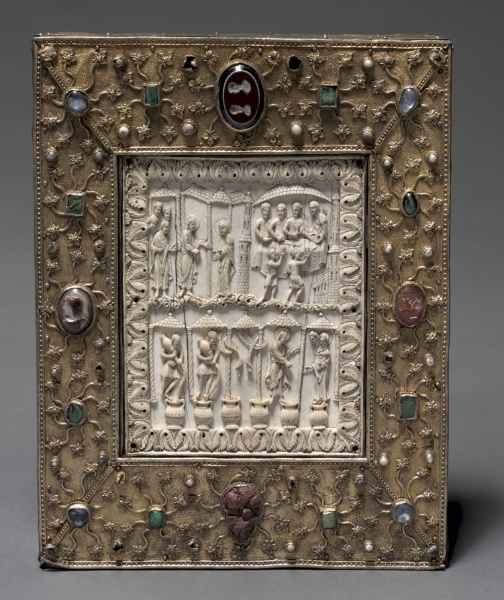

Cumdach, Book Shrine, Fancy Books

The Cumdach is a type of reliquary that resembles a book but was in fact a type shrine that would hold relics, or manuscriptal fragments.

Even today, we place important mementos or documents such as love letters or birth announcements within the pages of a family Bible or book of poetry, or even personal items within a faux dictionary safe placed on a bookshelf. This tradition of encasing our precious items has endured.

Treasure bindings were elaborately decorated book bindings, often made to show off, or demonstrate love for a text, or to be a valuable gift.

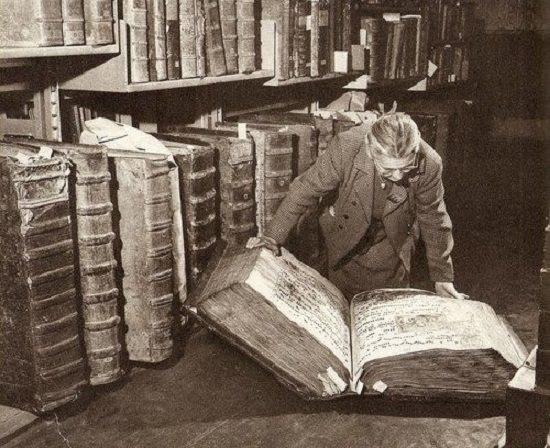

Scale

Often size was reflecting of importance so giant bibles were created, the most famous being Codex Gigas (weighing over 165 pounds) and containing a full-page devil.

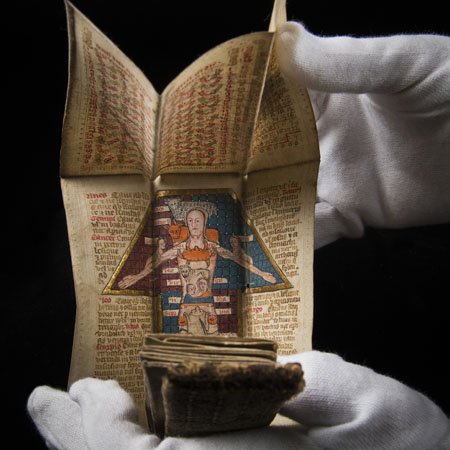

Folding almanac showing Zodiac man

Folding almanac showing Zodiac man

Physical Rituals

Kissing Images... Physical Rituals by Kathryn M. Rudy

created 2025-05-14, & modified,

=this.modified

rel:Kissing - The Art of Osculation Considered by George J MansonNOTE

In Lapiz Lazuli I was reading about this phenomenon of ritual osculation. The work cited referenced this paper.

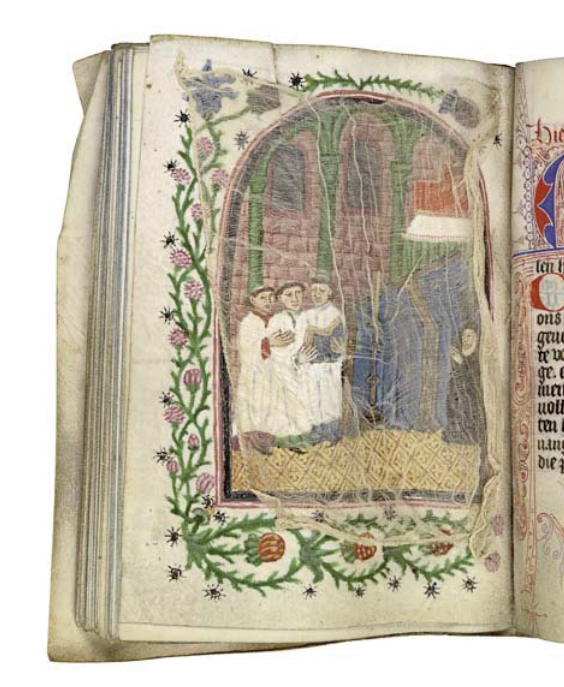

Christianity as practised in the late Middle Ages demanded physical rituals.

Manuscripts in particular often hold signs of wear, including dirt, fingerprints, smudges, and needle holes, which index some of the physical rituals they have witnessed.

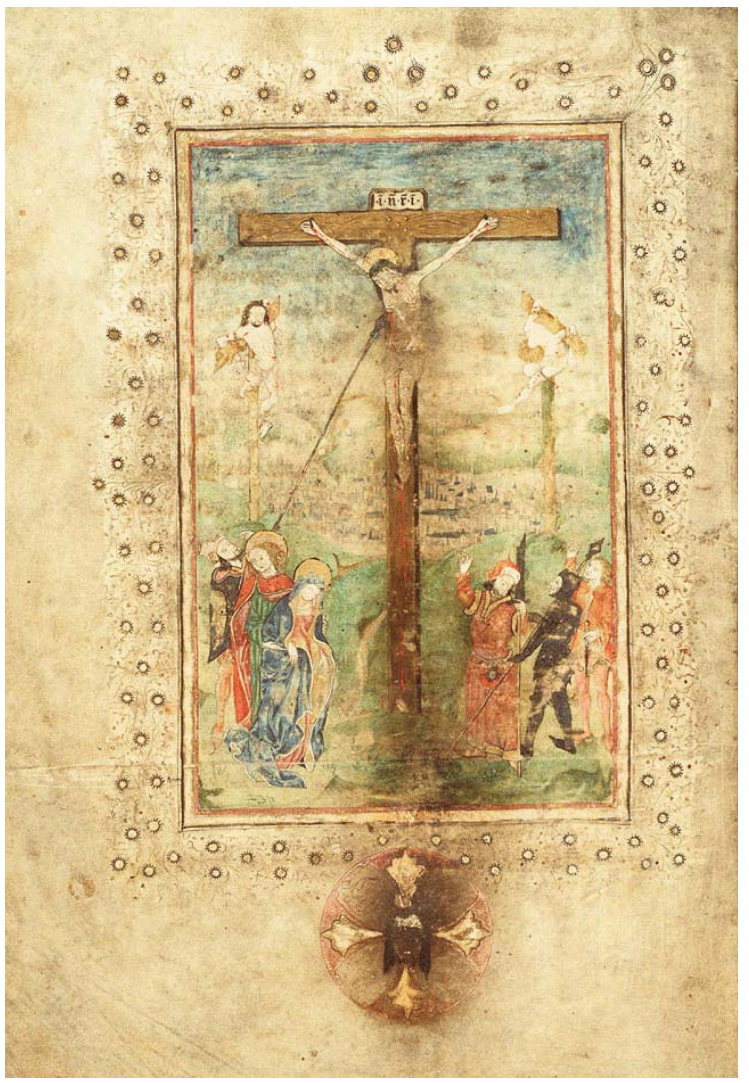

The physical relationship with the book, was because the worshippers used the book as a proxy for the body of Christ.

Like ingesting the host, the ritual continued to be oral, since the priest first kissed the pax before passing it to the congregants, who then kissed it to receive the kiss that had been spiritually deposited there.

Pax

Pax (Liturgical Object)

The Pax was a liturgical object used in the Middle Ages and Renaissance for the kiss of peace in Catholic Mass. Direct kissing was replaced by each in turn kissing the pax, which was carried around.

Often the pax was held out with a long handle attached, and it seems to have been given a wipe with a cloth between each person.

Believers understood that priests tapped into the power of Christ by repeating his words at the Last Supper: they uttered words that effected a change, just as priests uttered ‘hoc est corpus meum’ in order to turn the bread of the host into the body of Christ.

Devotional books use, both added and subtracted materials. Marginalia appears, and the binding functioned as a “lid of a treasure chest” with birth/death dates, extra prayers and small images.

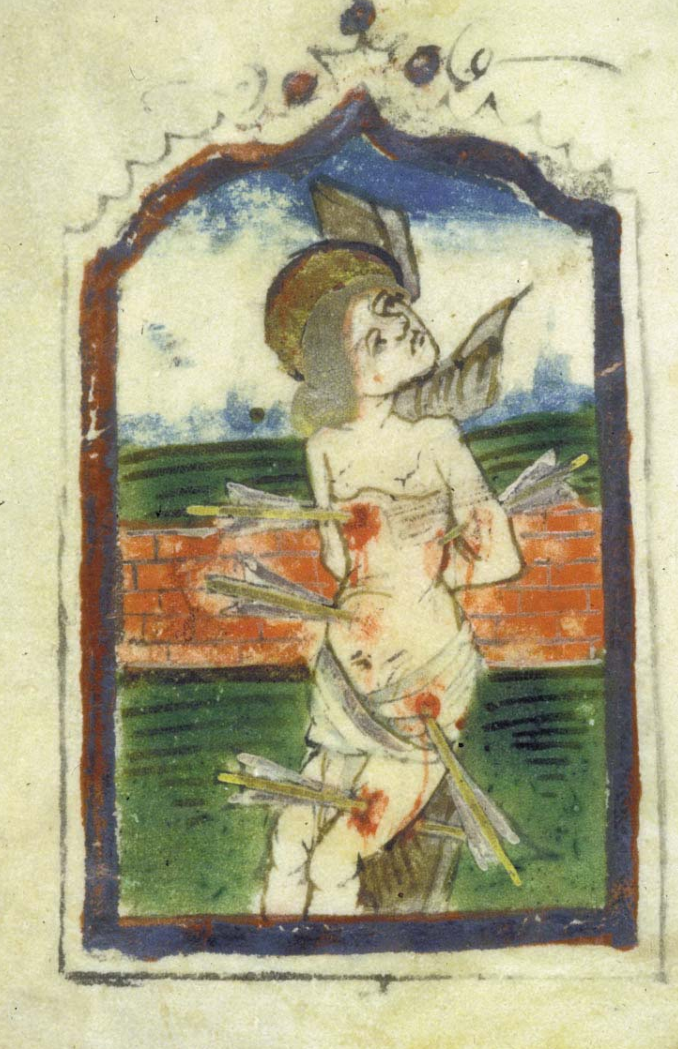

St. Sebastian was said to be efficacious against plague and other serious illness and invoking him may have had the same effect as invoking through prayer.

Item, anyone who speaks this prayer written below on an empty stomach every morning three times in front of the image of Our Dear Lady, along with one Ave Maria, will not die of the plague during the day.

The series of holes above the miniatures explains the reason for this discoloration: the votary sewed curtains to the book, thereby creating a row of needle holes. These curtains, which have since been removed, must have covered only the images and stopped short of the rubricated text below the frame.

Rubication

Rubication is the addition of red ink to manuscripts for emphasis.

Rubrication was used so often in this regard that the term rubric was commonly used as a generic term for headers of any type or color, though it technically referred only to headers to which red ink had been added.

Obliteration through kissing and handling

On the image of Christ on the cross,

Illuminators realized that priests would wear down the image with repeated use, so they painted small crosses at the bottom of the page to denote the place where the priest should aim his lips.

However, the image prefacing terce reveals the owner’s fiery enthusiasm for the body of Christ, as he (or she) touched the image repeatedly with her hands and possibly her lips (fig. 17). She has rubbed the nearly naked body of Christ right off the page, leaving his smeared silhouette against the gold-tooled background. Furthermore, she has combined the iconophilia for Christ’s naked body with iconophobia for the torturer at the right, resulting in a second set of spectral smears against the gold background. It is not clear, however, why she attacked only one of the torturers.

“worshipped to oblivion”

Wounds

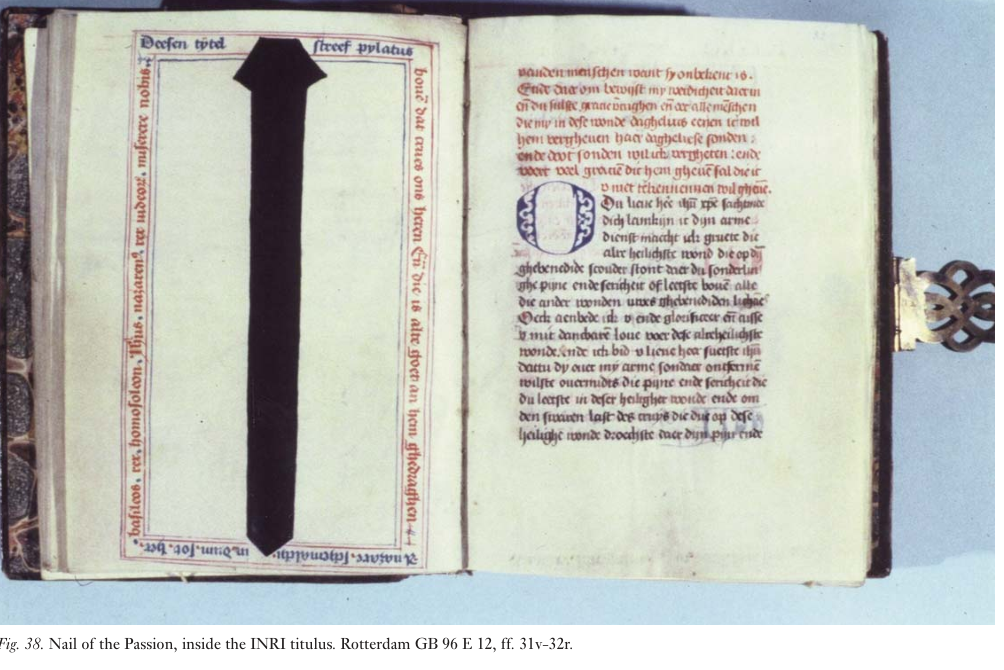

England in the fifteenth century, contains a variety of textual as well as image-based talismans, including schematic iconography from the Passion.

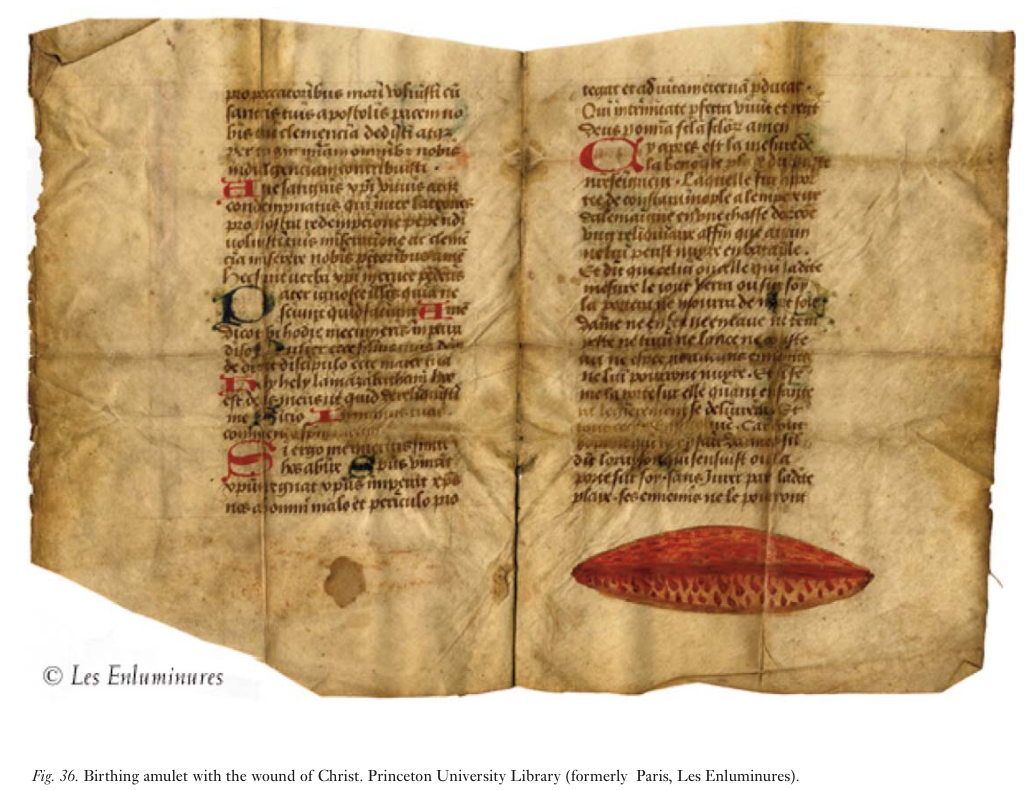

These included images painted on the roll of the wound of Christ and the nails of the Passion. These are known as metric relics, in that “their very dimensions correspond to a prototype and thereby summon the power of their referents.”

Link to original

Ship Library

Alexandria, as proclaimed by scholars of the time, was the intellectual capital of the Greek world. The greatest representation of this was the Library of Alexandria, the largest source of knowledge in the world. It was established by Ptolemy I in 290 B.C. and flourished under the Ptolemies as more and more works were added to it. Ptolemy II Philadelphus endowed it with the ambitious mission of procuring a copy of every book in existence. Ptolemy III Euregetes wrote a letter “to all the world’s sovereigns” asking to borrow their books. When the Athenians lent him the texts to Euripides, Aeschylus, and Sophocles, he had them copied, returned the copies, and kept the originals, gladly forfeiting the extravagant collateral which had been demanded for their safekeeping. All ships that stopped in the port of Alexandria were also searched for books and were given the same treatment, thus arose the term “ship libraries” for confiscated collections housed in the Great Library

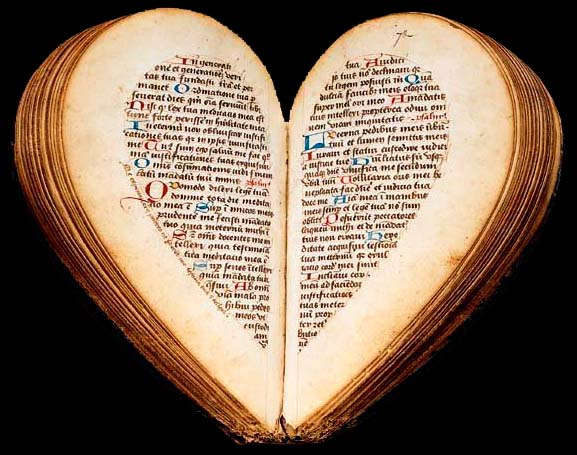

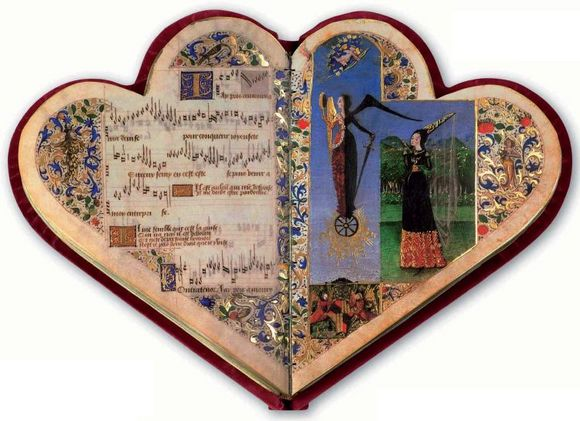

Heart Shaped Books

In shape of a single heart when book is closed and of two joined hearts when book is open. Copied by a single scribe. Copied in Savoy; compiled for Jean de Montchenu, a soldier and priest (later Bishop of Viviers) serving as Vicar-General and Councillor to Jean-Louis de Savoie, Bishop of Geneva. Subsequently owned by ‘Pucci,’ a Maltese nobleman. Listed in 19th-century library catalogues of Chédeau and Baron Jérôme Pichon (PicotC). Later acquired by the Paris banker Nathan James Edouard, Baron de Rothschild (1844-81), whose library went to his son Henri; passed to Bibliothèque Nationale in 1933.

Emblem Book

An emblem book was a book collecting emblems (allegorical illustrations) with accompanying explanatory text, typically morals or poems.

Each has an icon or image, a motto and text explaining the connection. Some were based around a theme, such as love.

Omnia vincit amor from Daniël Heinsius, Quaeris quid sit Amor 1601

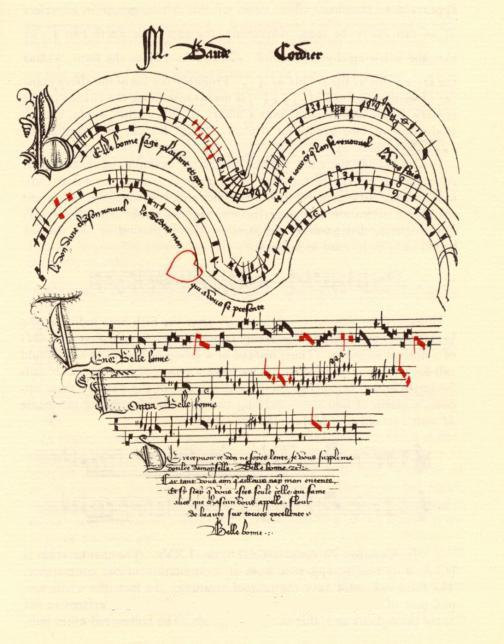

Baude Cordier

body-instrument From the early 15th century, Baude Cordier was the name of a French composer. Virtually nothing is known of Cordier’s life. He is best known for his unique and experimental notational methods, often with shapes related to subject matter.

Cordier’s rondeau about love, Belle, Bonne, Sage, is in a heart shape, with red notes indicating rhythmic alterations

In line with that cultural trend, he was fond of using red note notation, also known as coloration, a technique stemming from the general practice of mensural notation. The change in color adjusts the rhythm of a particular note from its usual form. (This musical style and type of notation has also been termed “mannerism” and “mannered notation.“)

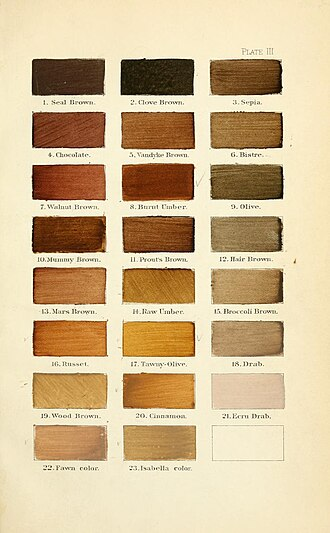

Mummy Brown

Otherwise known as Caput Mortuum (Latin for ‘dead head’, and variously spelled caput mortum or caput mortem), is a rich brown pigment that was made with the flesh of mummies mixed with white pitch and myrrh. In the mid-18th to 19th century it was very popular, but fresh supplies of mummies diminished and it was ceased to be offered by the 20th century.

Caput Mortuum

Also used as term in alchemy to signify a useless substance left over from chemical operations, and the epitome of decline and decay. They represented this residue as a stylized human skull, residue and residual.

The earliest record of the use of mummy brown dates back to 1712 when an artist supply shop called “À la momie” in Paris sold paints, varnish, and powdered mummy

The pigment was in such popular demand that the supply was too great, so true Egyptian mummies were substituted with the corpses of enslaved people or criminals. In aftermath of the French revolution the hearts of French kings were taken from the then Abbey of Saint-Denis and used to make paint. By 1849, it was described as being “quite in vogue.”

Martin Drolling’s Interior of a Kitchen

The Pre-Raphaelite artist Edward Burne-Jones was reported to have ceremonially buried his tube of mummy brown in his garden when he discovered its true origins

Anthropodermic bibliopegy

Anthropodermic bibliopegy (bookbinding) is the practice of binding books with human skin.

An early reference to a book bound in human skin is found in the travels of Zacharias Conrad von Uffenbach. Writing about his visit to Bremen in 1710:

(We also saw a little duodecimo, Molleri manuale præparationis ad mortem. There seemed to be nothing remarkable about it, and you couldn’t understand why it was here until you read in the front that it was bound in human leather. This unusual binding, the like of which I had never before seen, seemed especially well adapted to this book, dedicated to more meditation about death. You would take it for pig skin.)

What Lawrence Thompson called “the most famous of all anthropodermic bindings” is exhibited at the Boston Athenaeum, titled The Highwayman: Narrative of the Life of James Allen alias George Walton. It is by James Allen, who made his deathbed confession in prison in 1837 and asked for a copy bound in his own skin to be presented to a man he once tried to rob and admired for his bravery, and another one for his doctor. Once he died, a piece of his back was taken to a tannery and utilized for the book.