created, $=dv.current().file.ctime & modified, =this.modified

tags: Dada Surrealism

The plastic arts played on an ancillary role in Dada and Surrealism; they were held as useful means of communicating ideas but not worthy of delectation in themselves.

The Dadaist reaction was to “humiliate” art as Tristan Tzara advocated, assigning it a subordinate place in the supreme movement measured only in terms of life.

Breton: painting is a lamentable expedient in a world whose more and more necessary transformation was other than that which can be achieved on canvas.

Dada’s spread was inseparable from WWI, which seemed to confirm the bankruptcy of 19th century bourgeois rationalism (that logic could be used to justify the killing of millions revolted some men of sensibility.)

TT: “the beginning of Dada were not the beginnings of art, but of disgust.”

Jean Arp: “Dada wished to destroy the hoaxed of reason and to discover an unreasoned order.”

Breton: “the most Surrealist act” “going down the street… and shooting at random into the crowd” recalling Arthur Cravan - The Disappearing Dadaist and Jacques Vache (provocation) who disrupted an Apollinaire premiere threatening to shoot up the audience. “If it was realism to shoot a human being because he wore a uniform, it would be supprealism to apply the principle more broadly.”

TT each Dada act was a “cerebral revolver shot”

The value of work was in the act of making it, more than what it produced.

It was no so much art itself the Dadaist opposed but the idea that had been made of it, that is the autonomy of pure painting.

Duchamp gave it up in the midst of success as “not a goal to fill an entire lifetime.”

Emerging from the Cubist context of Parisian painting he sacrificed paints, brushes and canvas almost entirely to create an anti-art of Readymade objects and images on glass.

I wanted to put painting once again at the service of the mind. And my painting was, of course, at once regarded as “intellectual” “literary” painting. It was true I was endeavoring to establish myself as far as possible from “pleasing” and “attractive” physical paintings… The more sensual the appear a painting provided - the more animal it became - the more highly it was regarded.

Nude Descending a Staircase (No. 2) - “static representation of movement”

Hence the origin by fiat of the Readymades: man-designed, commercially produced utilitarian objects endowed with the status of anti-art by Duchamp’s selection and titling of them. In 1913 he placed a bicycle wheel upside down on a stool; singled out for contemplation in isolation from its normal context and purpose, it seemed strangely enigmatic, especially when the wheel turned pointlessly.

As intended epiphanies of irrational and even extra sensory experience the Readymades presuppose the existence of a “meta-world,” which Duchamp has described as “fourth-dimensional.” He explains that if a shadow is a two-dimensional projection of a three-dimensional form, then a three-dimensional object must be the projection of a four-dimensional form. Thus the simplest object holds the possibility of a revelation.

Duchamp’s progression from “anti-artist” to “engineer” was confirmed in 1920 when he ceased making images of machines and started to make actual ones. These, however, remained true to his ironic, Dadaistic view of experience in their absolute uselessness.

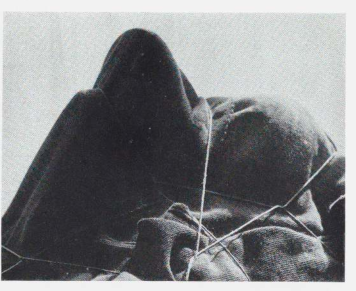

Man Ray worked on assisted readymades. His Enigma of Isidore Ducasse was a mysterious object, actually, a sewing machine of Ducasse-Lautreamont’s famous image- wrapped in a sackcloth and tied with a cord.

Lingering Cubism

Lingering Cubism

When more than one or two such shapes are used by the “abstract” Surrealists we almost always find them disposed in relation to one another and to the frame in a Cubist manner. Thus, while we may speak of the form- language or morphology of Arp, Masson, and Miro as anti- Cubist, this does not apply to the over-all structure of their compositions, since on that level these painters cling to organizational principles assimilated from the Cubism that all of them had practiced earlier.

Berlin Dada

Berlin produced less work of interest in the plastic arts than other Dada centers. Much of it was intentionally ephemeral: posters, impromptu pieces, propagandistic inventions manufactured for particular manifestations.

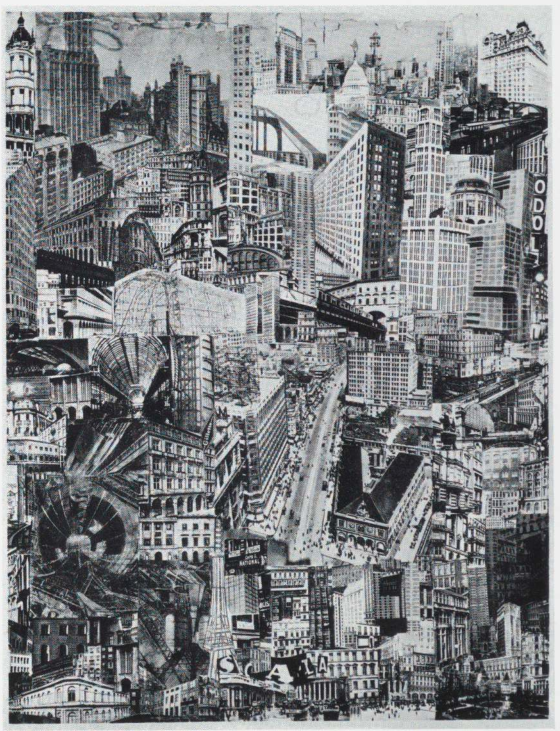

Berlin contributed photomontage - actually photo-collage, since the images were not montaged in the dark room.

rel: Bug on Sensor Transmutation and Transformation

In its pure form, photomontage entirely eliminated any need to paint or draw; the mass media could provide all the material.

Max Ernst on the experience that engendered collage:

Max Ernst on the experience that engendered collage:

One rainy day in 1919 … my excited gaze was pro voked by the pages of a printed catalogue. The advertisements illustrated objects relating to anthropological, microscopical, psychological, mineralogical, and paleontological research. Here I discovered the elements of a figuration so remote that its very absurdity provoked in me a sudden intensification of my faculties of sight—a hallucinatory succession of contradictory images, double, triple, multiple By simply painting or drawing, it sufficed to add to the illustrations a color, a line, a landscape foreign to the objects represented—a desert, a sky, a geological section, a floor, a single straight horizontal expressing the horizon, and so forth. These changes, no more than docile reproductions of what was visible within me, recorded a faithful and fixed image of my hallucination. They transformed the banal pages of advertisement into dramas which revealed my most secret desires.

Ernst wanted to go beyond painting, not like Duchamp (beyond art). Plasticity was a second interest; he used the borrowed elements primarily for their image value, joining them in irrational disconcerting ways.

Collage: a meeting of two distant realities on a plane foreign to them both. Collage: a culture of systematic displacement and its effects

rel:In Search of Lost Art - Schwitter’s Merzbau

Schwitter’s Merzbau or Merz Structure, which he transformed his home.

I could not, in fact, see the reason why old tickets, driftwood, cloakroom tabs, wires and parts of wheels, buttons and old rubbish found in attics and refuse dumps should not be as suitable a material for paint ing as the paints made in factories. This was, as it were, a social attitude, and artistically speaking, a private enjoyment, but particularly the latter…

Schwitters improvised Environment gradually obliterated the architectonic sense of his house.

Thought

Reminds me of (the Mole Man documentary) and Luna Parc in upstate NY.

The Merz accumulations began to be surrounded by an organic growth of wood and plaster which in time extended through two floors of the building and down into a cistern. As this shell was realized it became increasingly Constructivist in style, in keeping with the general reorientation of Schwitters’ art in the mid-twenties. It is this more purely plastic apparatus that the photographs best preserve for us (the house was destroyed by bombs in 1943)5^ the inner core, formed of Men agglomerations, amounted to a kind of Dada grotto, part of which was accessible only through doors” and “windows” in the surrounding timber struc ture. Among the names Schwitters gave to sections of the Merzbau were Nibelungen Treasure, Cathedral of Erotic Misery, Goethe Grotto, Great Grotto of Love, Lavatory Attendant of Life; there was also a Sex-Murder Cave, which contained a red-stained broken plaster cast of a fe male nude.

Rauschenberg converted his own pillow and quilt into a painting called Bed

On Bed from MoMA site

Bed is one of Rauschenberg’s first combines, a term he coined to describe the works resulting from his technique of attaching found objects to a traditional canvas support. In this work, however, there is no canvas. The artist took a well-worn pillow, sheet, and quilt, scribbled on them with pencil, splashed them with paint in a style similar to Jackson Pollock’s action paintings, and hung the entire ensemble on the wall.

The story goes that Rauschenberg used his own bedding to make Bed, because he could not afford to buy a new canvas. “It was very simply put together, because I actually had nothing to paint on,” he reflected years later, in 2006. “Except it was summertime, it was hot, so I didn’t need the quilt. So the quilt was, I thought, abstracted. But it wasn’t abstracted enough, so that no matter what I did to it, it kept saying, ‘I’m a bed.’ So, finally I gave in and I gave it a pillow.”

The Pioneer Years of Surrealism 24-29

The word “surrealism” had been used first by Apollinaire in 1917 in a context that coupled avant-garde art with technological progress; his neologism possessed none of the psychological implications that the word would later take on.

Breton:

surrealism, noun, masculine. Pure psychic automatism, by which one intends to express verbally, in writing or by any other method, the real functioning of the mind. Dictation by thought, in the absence of any control exercised by reason, and beyond any aesthetic or moral preoccupation. encycl. Philos. Surrealism is based on the belief in the superior reality of certain forms of association heretofore neglected, in the omnipotence of dreams, in the undirected play of thought… .

“I believe,” Breton proclaimed, “in the future resolution of the states of dream and reality, in appearance so contradictory, in a sort of absolute reality, or surrealite, if I may so call it.”

At the time of conception, no conception of Surrealist painting existed.

The Surrealists eschewed perceptual starting points and worked toward an interior image, whether this was conjured improvisationally through automatism or recorded illusionistically from the screen of the mind’s eye.

In 1917 de Chirico suddenly lost his muse and began his progression toward the kind of meretricious painting that has since been associated with his name. Though Breton became disenchanted with de Chirico’s subsequent pictures, he looked back on the painter as a “great sentinel” on the route to be traveled by Surrealism. Lautreamont and de Chirico, wrote Breton, were the “fixed points” that “suf ficed to determine our straight line.”

rel:Automatic Writing - Automatism - Surrealistic Techniques Remedios Varos

Ernst discovers frottage: … I was struck by the obsession imposed upon my excited gaze by the wooden floor, the grain of which had been deepened and exposed by countless scrub- bings. I decided to explore the hidden symbolism of this obsession, and to aid my meditative and halluci natory powers, I derived from the floorboards a series of drawings by dropping pieces of paper on them at random and then rubbing them with black lead… . The drawings thus obtained steadily lost the character … of the wood, thanks to a series of suggestions and transmutations that occurred to me spontaneously (as in hypnagogic visions), and assumed the aspect of un believably clear images probably revealing the original causes of my obsession… .

Exquisite Corpse - The technique got its name from results obtained in an initial playing, “Le cadavre exquis boira le vin nouveau” (The exquisite corpse will drink the young wine).

30s Surrealism

1929 was year of crisis and redirection for Surrealism. The movement was intended to function as a spontaneous expression of affinities between independent collaborators. One after another participants in this “collective experience of individualism” were forced to choose between the polar terms of the formula (collective/individual).

Dali:

My whole ambition in the pictorial domain is to materialize the images of concrete irrationality with the most imperialist fury of precision. - In order that the world of the imagination and of concrete irra tionality may be as objectively evident, of the same consistency, of the same durability, of the same per suasive, cognoscitive and communicable thickness as that of the exterior world of phenomenal reality… . — The illusionism of the most arriviste … art, the usual paralyzing tricks of trompe-l’oeil, the most … discredited academicism, can all transmute into sub lime hierarchies of thought

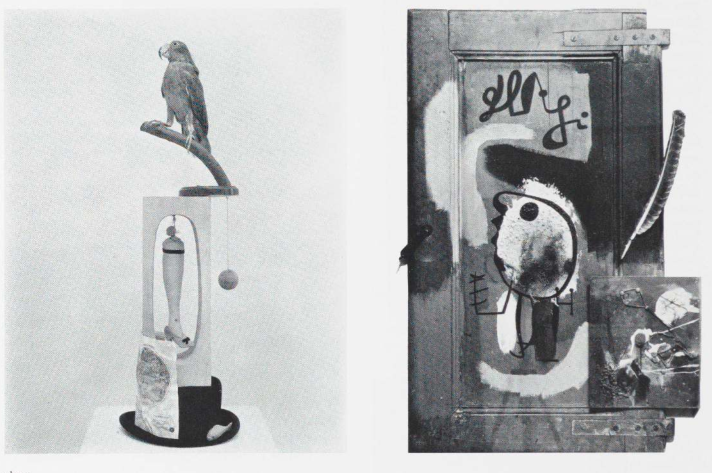

The Surrealist object was essentially a three-dimensional collage of “found” articles that were chosen for their poetic meaning rather than their possible visual value. Its entirely literary character opened the possibility of its fabrication —or, better, its confection —to poets, critics, and others who stood professionally outside, or on the margins of, the plastic arts.

Hans Bellmer visited Paris and joined the Surrealists. His strange “dolls” had been conceived earlier, but their development suggested a quasi-Expressionist counter part to Surrealist objects, particularly those that included clothes dummies or the type of mannequins that were to play such a central role in the great Surrealist exhibition of 1938.

In Exile and After

Pollock used automatism as a means of getting the picture started, and, like the Surrealists, believed that this method would give freer rein to the unconscious.

His painting not only went beyond the wildest speculations of Surreal ism in the extent of its automatism, but in its move toward pure abstraction, was alien to the Surrealist conception of picture-making. Nevertheless, as Pollock relaxed his drip style in the black-and-white paintings of 1951, fragments of anatomies— some monstrous and deformed, others more literal surfaced again, as if the fearful presences in his work of the early forties had remained as informing spirits beneath the fabric of the “all-over” pictures.