created 2024-07-03, & modified, =this.modified

Unravelling an Ancient Code Written in Strings by Professor Sabine Hyland

When Sabine was granted access to the quipu they were hidden in secret areas under sacristy in churches. Now they’ve been pulled back into deeper hidden recesses to avoid destruction. Many villages appear to have their own relic, and follow this pattern of retreat upon threatening. They have allowed certain researchers like Sabine to document and thus provide cultural weight that would preserve their spaces as modernity encroaches and children move to places like Lima.

Often nobody can read the Quipu. They are popularly seen as recording devices, but there are traits of logosyllabic writing and certain Quipu are remembered as epistolary, documentation of warfare.

They appear to be more than databases, but “no specific Quipu has been reliably identified as a narrative text.

This is what I find interesting, the possibly they have this record which is passed on through generations and is currently indecipherable but now woven into myth and narrative and taken on that meaning. Not saying this is the case. I’m wondering if the documents have taken on this new light, where they are interfaced with myth due to that gap in understanding.

To them, “the cords have their own sentience”, there’s an interlude where her entry to the village coincided with appearance of native herd, which they associated. The cords are woven with the furs of different native animals. Each of these animals provide symbolic meaning to deciphering the text. Feeling these differences in the hand is critical to understanding.

Modern locals have used a style of Quipu in funerary practices. They encode prayers. All relatives come together in grieving to construct a Quipu to be wrapped around the deceased.

Spanish destroyed Incan record, attempting to replace writing and numeral systems. Deciphering Quipu could provide access to primary records. Quipu were also seen as a form of idolatry, and destroyed hence their current clandestine status.

Many Quipu now have been placed in Museums and thus distanced from their culture and the groups who would be able to provide history and meaningful association to them. The people here are physically removed from their historical language. They show signs of edits. Kinks remain where places were once knotted, as if records were cleared at the end of year. These were also communal communication devices. Quipus would be worn, wrapped around head, chest. Buried with a boy wrapped on chest.

Twisted Cords

Analysis of the khipus reveals that they contain 95 different symbols, a quantity within the range of logosyllabic writing systems, and notably more symbols than in regional accounting khipus. Virtually all extant khipus are conserved in university, museum and private collections Evidence suggests that Andeans composed khipu epistles during the rebellions to ensure secrecy and affirm cultural legitimacy Inka runners, known as “chasquis”, carried khipus as letters during the Inka period Colonial manuscripts in Collata’s sacred box reveal that members of this community spoke Quechua in the past, although villagers today are monolingual Spanish speakers. Therefore, if the symbols of the Collata khipus had any link to spoken language, the language would have been Quechua, not Jaqaru or Kawki Each khipu commences with a multicoloured bundle, known locally as a “cayte”, which signifies both the beginning and the subject matter of each khipu (Hyland 2016). Khipu B’s cayte (3.8cm long) consists of a tuft of bright red deer hair wrapped with light brown vicuña threads.

Village authorities insisted on handling the khipus without gloves to feel the fibre differences Two senior herders assigned to assist me identified the animal fibres of the pendant cords (in order of decreasing frequency): vicuña, alpaca, guanaco, llama, deer, and vizcacha. The herders insisted that the fibre type conveyed meaning, stating that khipus represented “a language of animals”. Ply direction has been shown to be a semiotic feature signifying binary oppositions on khipus This explains the pun/rebus connection. Very interesting.

Modern catechetical “cakes” represent prayers through items set into clay using rebuses. For example, a tuft of llama wool can represent the Spanish “se llaman” — “they are called” — because of the similarity between “llama” and “llaman” Likewise, a blade of “ichu” grass often signifies “Jesús” because of the similarity of sounds This proposed decipherment suggests that khipu pendants may possess standard syllabic values My layman understanding here is that there was this cultural/custom shared mnemonic system, obviously lost to time which would provide access to deeper understanding of the corded documents. It’s unsure if these modern Quipus represent a direct link To the methods of the incan ones, or are a modern innovation. Musems = 800 Quipus, but once 100,000s Some forgeries seem to exist in museums and could also be in the datasets.

Modern catechetical “cakes” represent prayers through items set into clay using rebuses. For example, a tuft of llama wool can represent the Spanish “se llaman” — “they are called” — because of the similarity between “llama” and “llaman”

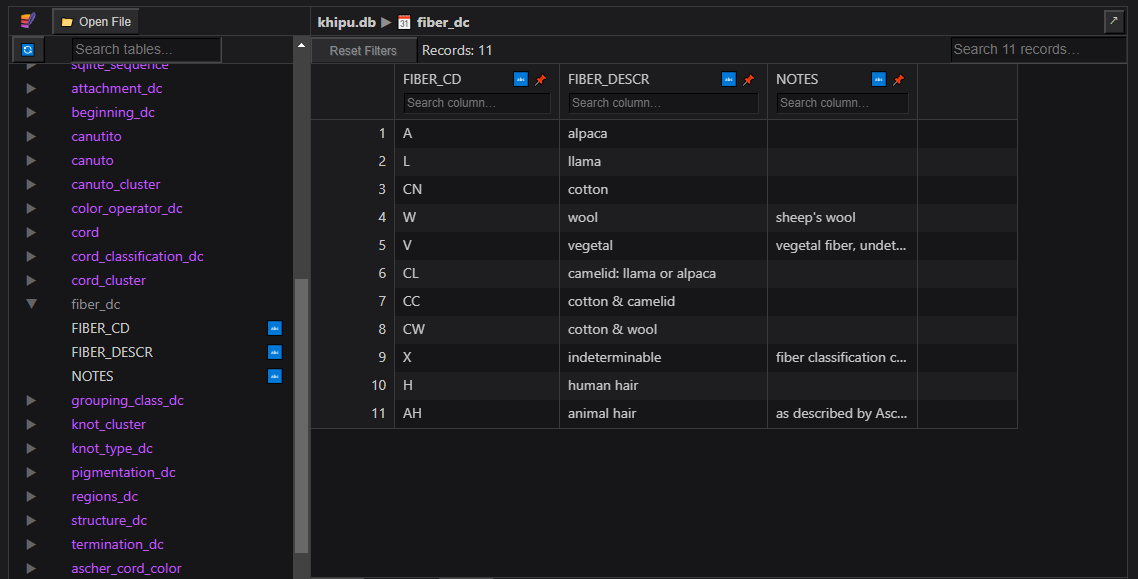

SQLite

Examining the open database of quipus.

A seeming database system of animal hairs, cloth and metal later taking on this air of an encoded myth and a language of animals, then being stored in a computer db. Wow.

This open-source digital repository stores the most up-to-date data and metadata on extant Inka-style khipus from archaeological sites in the Andes, as well as museums around the world. Inka khipus were unique pre-Columbian, Andean recording devices that used three-dimensional signs — primarily knots, cords, and colors — as symbols functionally akin to those of early writing systems in other cultures. Spanish chronicles, as well as contemporary khipu studies indicate that the Inka used khipus to record everything from accounting records to historical narratives. The khipu recording system remains undeciphered, however. The purpose of this repository is to enable computational khipu research and Inka khipu decipherment efforts.

Quipu Course

[link](https://courses.csail.mit.edu/iap/khipu/)

Students will divide into groups. Each group will develop their own way of “writing with rope”—developing a written language like quipu. The method can use all or only some of what we know about actual quipu (e.g., the different types of knots used). These languages will be interesting in their own right, but they may also shed light into plausible approaches taken by the Incas. Each group will also work on breaking the code developed by another group. This will give us experience in recognizing different types of codes, and ultimately in decoding actual quipu.