created 2025-06-15, & modified, =this.modified

rel: Jean Tinguely]

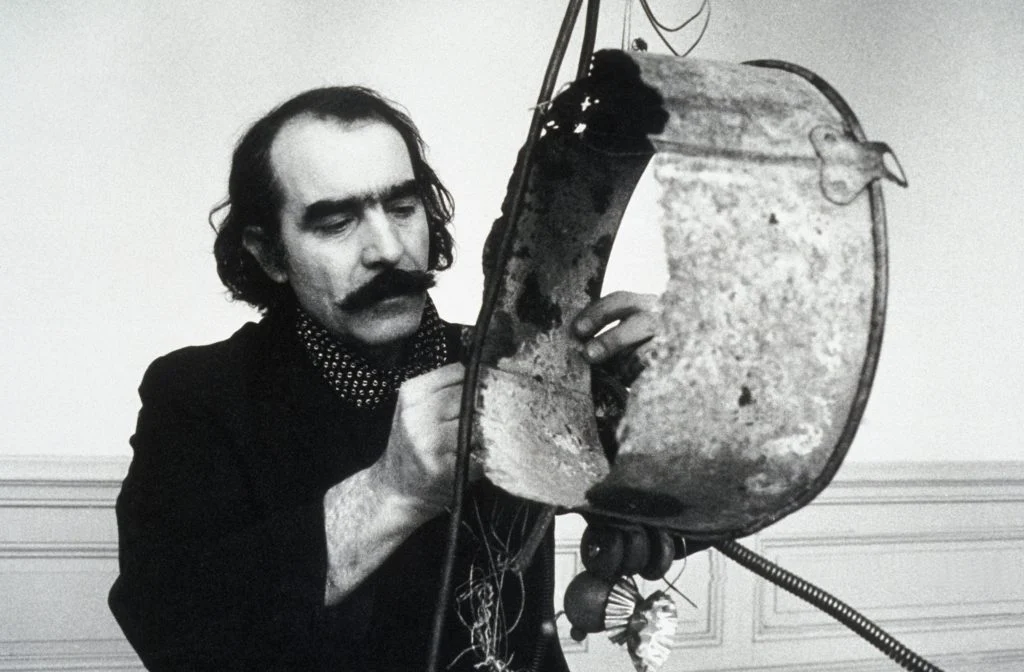

In Machine Spectacle

Before there’s a sculpture it’s just a machine. Just a machine who does nothing. Just moving by herself and enjoying people, maybe or making people mad too sometimes. Sometimes making people angry or bringing problem to people.

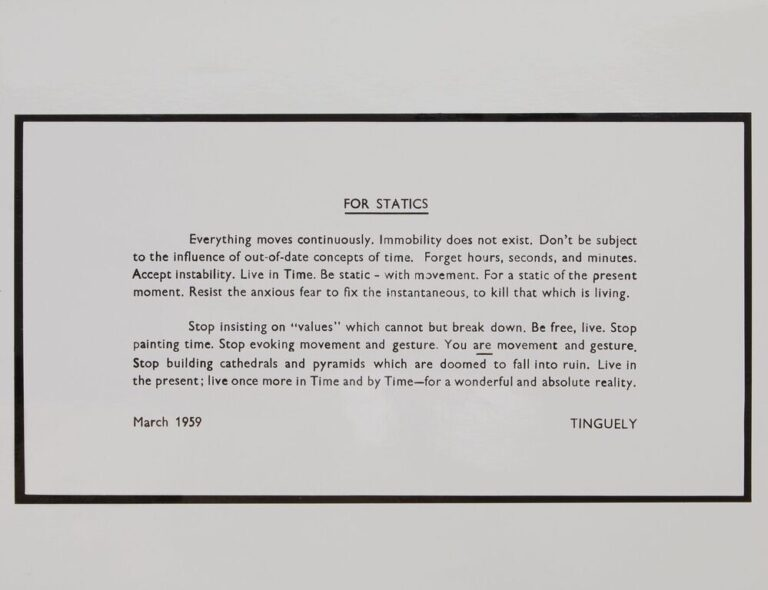

For Statics

Tinguely dropped 150K copies of his manifesto Für Statik on Dusseldorf and its suburbs. This action made clear reference to the dropping of propaganda leaflets during WWII which had only ended 14 years earlier.

If connected to the electrical infrastructure, the useless machines would divert public utilities for the purpose of creating nothing.

Hommage a New York

“The work had to pass by, make people dream and talk, and that would be all,” the artist commented, “the next day nothing would be left.”

Battered itself to pieces in 1960 in MoMAs sculpture garden. Witnesses attending its self-destruction were encourages to take pieces home as souvenirs.

A whirring object made of found objects like pieces of dismantled bicycles, musical instruments, a bathtub, and a go-cart would eventually build up enough energy to burst into flames and disintegrate, to the surprise of audience members and museum officials alike. The performance was shut down by the fire department and some surviving remnants of the burnt structure were salvaged and remain on view at the museum today.

Niki de Saint Phalle

The woman above is Niki de Saint Phalle

Drawing Machine Meta-Matics

rel: Externalized Action

Tinguely was one of the pioneers in the field of art that engenders social engagement. In the late 1950s, he designed a series of automatic drawing machines, the Meta-Matics, which use chalk or markers to make abstract drawings through a mechanized process. These were portable machines with drawing arms that allowed the spectator to produce abstract works only by pushing the button. The “painting machines” were exhibited at the Biennale de Paris in 1959, resulting in almost 40,000 paintings produced by visitors in two weeks. However, not all of the Meta-matics functioned properly, and Tinguely destroyed some of them.

Meta-matic drawings vary enormously, entirely according to how the machine is set up and used. No two drawings are ever completely identical. How close the felt-pen, or whatever is being used, is fixed to the paper, is an important factor, but the fluidity or otherwise of of the colouring agent, or the texture of the paper, will also play a part. The operator can use pencil, ballpoint, airmail stamps, invisible ink … The decisive thing is how long the machine is allowed to run without interference, and how long with each separate colour. But however it is set up, it is impossible for the machine to produce an ugly drawing.

When a viewer turns on a machine by inserting a token, the first arm scribbles frantically on the paper. Reviews indicate that early viewers were able to select and insert their choice of drawing implements, to stop and start the machines in order to change these implements, and at least in some cases, to choose among a selection of drawing speeds.

The drawing machine created a drawing each time it is operated. This lead to some confusion in where the art was – is the machine itself or the product?

Tinguely emphasized this focus of consumption and exchange by requiring tokens to start the Méta-Matics, and asking spectators to purchase tokens with real money.

The tokens were printed with Tinguely’s name and the first names of his friends and associates—including “Pontus,” “Yves,” and “Iris”—drawing an equation between currency and the proper name, and also perhaps calling attention to the figures who had bestowed his work with its economic value..

A experience of the exhibition is detailed. The reporter goes to the gallery and pays five shillings for a token. The receptionist says “You picture won’t really be worth 5s, but M. Tinguely feels you will get more out of the experience if you have to pay something first.”

Rather than an honest worker, the artist could now be understood as the owner of the means of production, required to work less because he could control and benefit from his machines’ labor.

A pimp from the Paris red-light district comes to him:

*The Corsican congratulated him in these words: ‘You’re really someone, the king of us all. People put money in your machines; the machines do the work, and the customers even help it: they stop when the drawing’s finished, then they come and ask for your signature and congratulate you. That’s money for jam..

William Rubin’s understanding of the machines: “Their perhaps unintentional revelation was to confirm that painting is almost entirely a matter of decisions following from conception, as distinct from facility in techniques of execution.”

In Tinguely’s work, we might understand the very paucity of the viewer’s contribution as a parody of the idea of “choice” in consumer society—the significance attached to the selection between minimally differentiated models, such as a red car over a black car, that masks a deeper lack of real personal choice in the face of the capitalist economy.

One Italian journalist reporting on the drawing machines attributed different temperaments to them: one initially moved “with laziness, as if it had no desire to begin painting,” and then later with a kind of crazed violence, “as if it hated the man who had awoken him with the torture of the electric current.”

Méta-Matic nr 17

Some drew connections between the machines and drawing animals.

Lolo the Donkey

Joachim-Raphaël Boronali was a fictitious Italian painter created as an invention of writer and critic Roland Dorgelès who created paintings on canvas by tying a paintbrush to the tail of a donkey named Lolo.

Lolo exhibited “Sunset Over the Adriatic” in 1910 and the painting sold for 400 franc ($1.4K in 2024 value).

Boronali:

Holà! Great excessive painters, my brothers, holà, sublime and renovating brushes, let’s break the ancestral palettes and lay down the great principles of tomorrow’s painting. His formula is Excessivism. Excess in everything is a defect, said a donkey. On the contrary, we proclaim that excess in everything is a strength, the only strength… Let’s ravage absurd museums. Let’s trample on infamous routines. Long live scarlet, purple, coruscating gems, all those swirling, superimposed tones, the true reflection of the sun’s sublime prism: Long live excess! All our blood to recolor the sick auroras. Let’s warm art in the embrace of our steaming arms!

According to writer Robert Bruce, after Frédé’s [the owner’s] death, his donkey Lolo was placed in Normandy. He was later found drowned in a pond, which led people at the time to think the animal had committed suicide.

The drawings and the machines brought up questions related to surrealistic automatism and intentionality. Pierre Jacquemon argued that the machines should be understood as tools akin to brushes and pencils. The machine may be unaware, but the creator is – what he called “willed automatism.”

Robert Lebel says they should not be read as a serious attack on painting. They mock the “exhaustion of pictorial inspiration.” If observers feel threatened they should also be concerned about the seismograph or electrocardiograph.

Robert Estivals, a linguistic and former member of the Lettrist movement poses a question in terms of semiotics. He argues they are machines that are producing natural signs. Like Course in General Linguistics by Ferdinand de Saussure – a sign is made of a signifier and signified, which are united like two sides on a sheet of paper. In a natural sign the signifier is the direct or automatic expression of the signified. These machines fall into objective reality, such as smoke or thunder. “Yet he also acknowledges that the drawings come very close to the subjective signs, as it is the artist who made the machine—it did not occur randomly in nature. His response points to a confusion we have already encountered: whether the art of the Méta- Matics lies in the machine or the product.”

For all of this academic consideration the response of the public was laughter, humor and enchantment. The machines were not a threat – purely useless.

Tinguely’s aim in these machines, whose parts slide around their surfaces or which scribble marks on a page, was to question the extent to which choices required a subjectivity to guide and motivate them, and to dispute the idea that drawing gave access to some deeper level of self.

For Tinguely, then, kinetic animacy had its limits. If his machinic parts had a “life of their own,” it was lived purely at the surface level: there was never any real question as to what lay beneath.

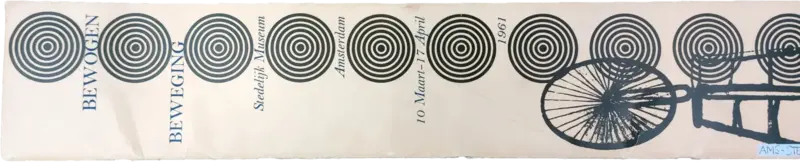

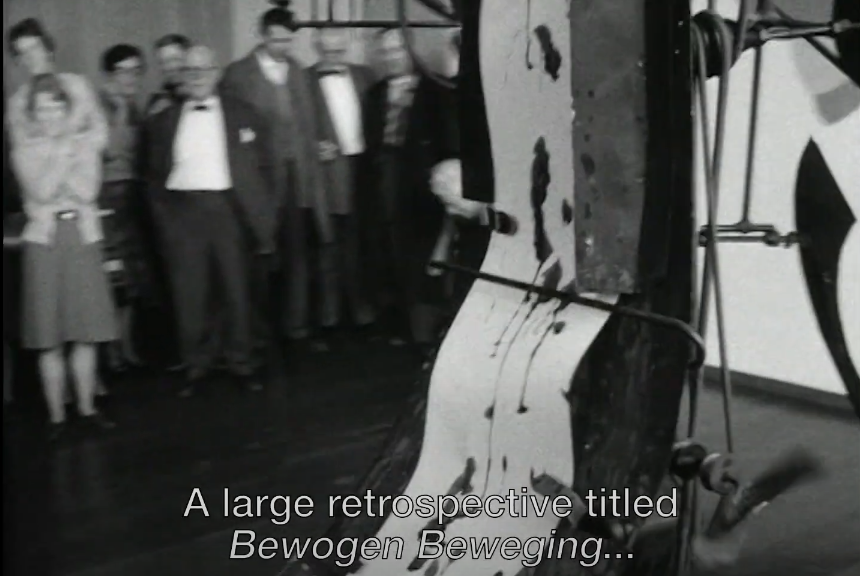

Bewogen Beweging Exhibition

Kinetic art exhibition.

Although attendance figures for the exhibition were high, the show attracted some criticism from artists. George Rickey, in his review of the exhibition in Amsterdam published in Arts Magazine, September 1961, criticised the exhibition for ‘the neo-Dada bias in the contemporary section and the beautification of Tinguely’.

This

I can’t tell where this one is from, but want to know. It moves and ink drips.

Audience members could help switch on the art, or produce their own art.

Cyclograveur

The absurdity of a machine endowed with human characteristics addressed the Dutch anxiety about rapid industrialization by poking fun at the “promises” of automation. By presenting a purposeless object that subverted the functionality of the very purposeful bicycle, Cyclograveur humorously encouraged visitors to question their presumptions about machines and their expectations of the coming “machine age”.

The Animate Object of Kinetic Art Chapter1

What consequences arise once the labor of composition has been delegated to a machine?

Thought

Concrete in relation to grounding –

A large number of these artists identified their work as “concrete,” a term meant to affirm the nature of artistic elements as belonging to, rather than derived from, the real world. That is, painted lines, shapes, and surfaces were not to be considered abstracted representations of objects, or even as representations of mental ideas, but were to be new creations continuous with our own reality.

Munari’s Manifesto of Machinism in 1952

The text warned of the potential danger of machines, which were making increasing demands on their human caretakers: “they already force us to take care of them… we have to keep them clean, provide them with nourishment and rest, continually visit them and make sure they are lacking in nothing. In a few years we will be their little slaves.”

In this climate, artists could no longer afford to continue working with brushes and canvas. Rather, they must learn more about the nature of machines—“their moods, their nature, their animal defects”—and ultimately “divert them to function in irregular ways.”58 It was only by rerouting the machine toward nonutilitarian functions that humans could avoid domination by technology

Manifesto of Machinism

Today’s world is a world of machines.

We live among machines, they help us with everything we do in our work and recreation. But what do we know about their moods, their natures, their animal defects, if not through arid and pedantic technical knowledge?

Machines reproduce themselves faster than mankind, almost as fast as the most prolific of insects; they already force us to busy ourselves with them, to spend a great deal of time taking care of them; they have spoiled us; we have to keep them clean, provide them with nourishment and rest, continually attend to them and meet their every need. In a few years’ time we will become their little slaves.

Artists are the only ones who can save mankind from this danger.

Artists have to be interested in machines, have to abandon their romantic paint-brushes, their dusty palettes, their canvases and easels.

They have to start understanding the anatomy of machines, the language of machines, their nature, and to re-route them into functioning in irregular ways to create works of art with the machines themselves, using their own means.No more oil paints but blowtorches, chemical reagents, chroming, rust, coloring by anodes, thermal alterations.

No more canvases and stretchers, but metals, plastics, synthetic rubbers and resins.

The form, color, movement, noise of the world of machines no longer viewed from without and deliberately reproduced, but harmoniously composed.

Machines today are monsters!

Machines must become works of art!We shall discover the art of machines!