created 2025-05-04, & modified, =this.modified

tags:y2025artarchitectureholes

rel: Ruins and Fragments by Robert Harbison In Search of Lost Art - Schwitter’s Merzbau Horror In Architecture

Gordon Matta-Clark was an artist, best known for site specific works. He also pioneered socially engaged food art.

He did not practice as a conventional architect; he worked on what he referred to as “Anarchitecture”

FOOD in Soho

FOOD was a place where artists in SoHo, especially those who were later involved in Avalanche magazine and the Anarchitecture group, could meet and enjoy food together.

It was a project meant to bring the artists together. Artist were invited to be chefs, as well as working at the restaurant. There was no ordering of many dishes, diners ate what was offered on that day in a plain, affordable menu.

It was one of the first restaurants in NYC to serve sushi, and vegetarian meals.

Anarchitecture

A portmanteau of Anarchy and Architecture – to suggest an interest in voids, gaps, and leftover spaces.

Fake Estates

rel: Odd Lots - Revisiting the Fake Estates of Gordon Matta-Clark

In the summer of 1973, artist Gordon Matta-Clark discovered that the city of New York occasionally auctioned improbably tiny and frequently inaccessible parcels of land created by zoning eccentricities. Fascinated by these spaces, he bought 15 of them (14 in Queens, and one in Staten Island) for between 75 each, photographed them and collated the photographs with the appropriate deeds and maps. He called the project Fake Estates.

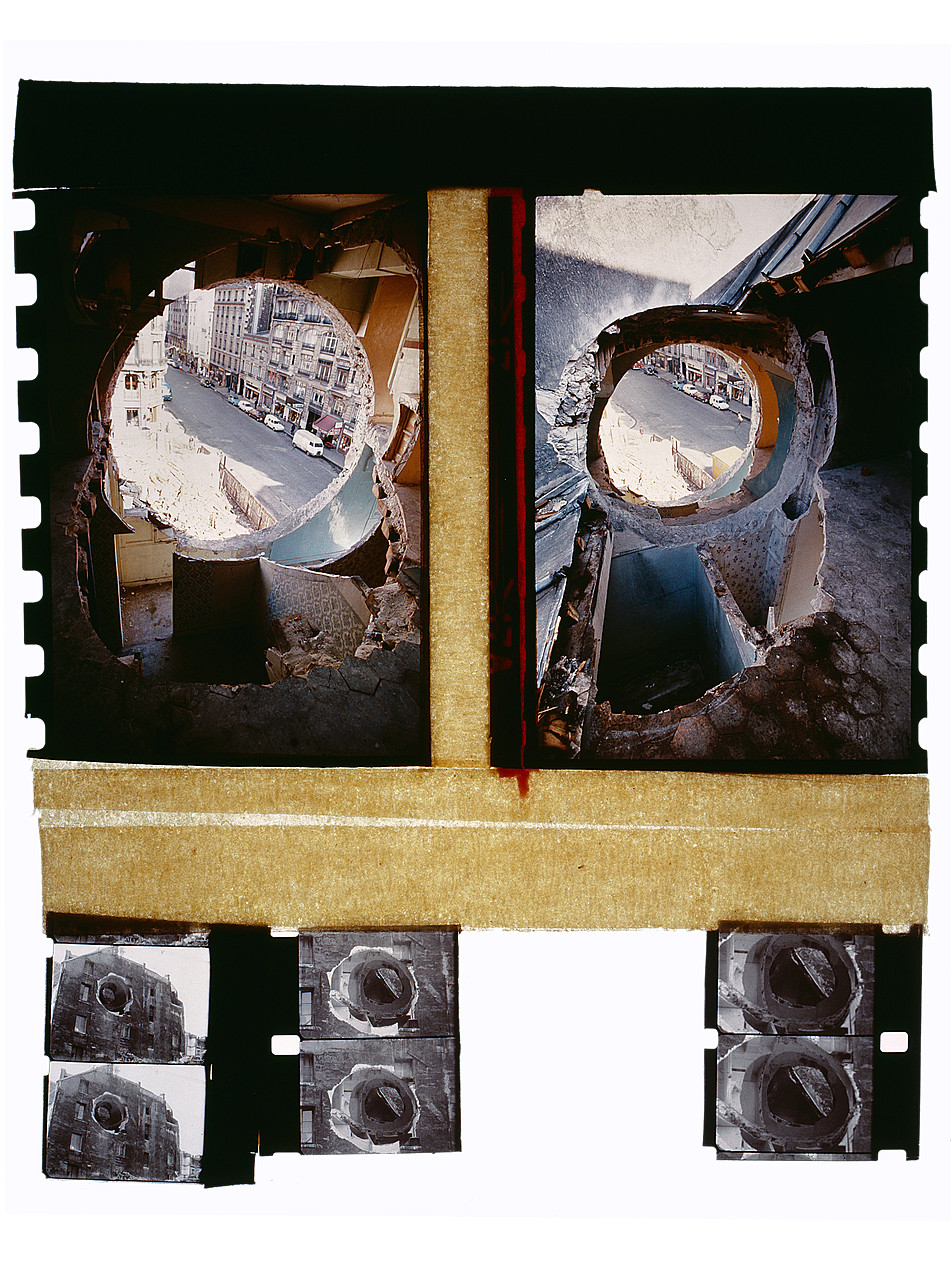

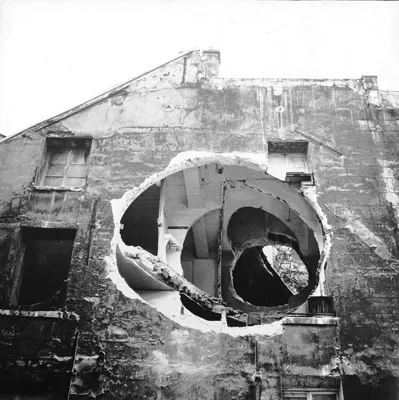

Conical Intersect

“Completion through removal. Abstraction of surfaces. Not-building, not-to-rebuild, not-built-space. Breaking and entering.”

Conical Intersect, Matta-Clark’s contribution to the Paris Biennale of 1975, manifested his critique of urban gentrification in the form of a radical incision through two adjacent 17th-century buildings designated for demolition near the much-contested Centre Georges Pompidou, which was then under construction. For this antimonument, or “nonument,” which contemplated the poetics of the civic ruin, Matta-Clark bored a tornado-shaped hole that spiraled back at a 45-degree angle to exit through the roof. Periscopelike, the void offered passersby a view of the buildings’ internal skeletons.

Day’s End/Passing (Pier 52)

“Abandonment” is a falsely ultimate moment; “abandoned” a misnomer. For, once an obsolete use-relation has terminated, neglect institutes a cooling-off period, a no-man’s time for the land, after which “dead” space can be renovated and reinserted into real estate exchange.

NOTE

David Hammons made a structure in place.

“The determining factor is the degree to which my intervention can transform the structure into an act of communication.”

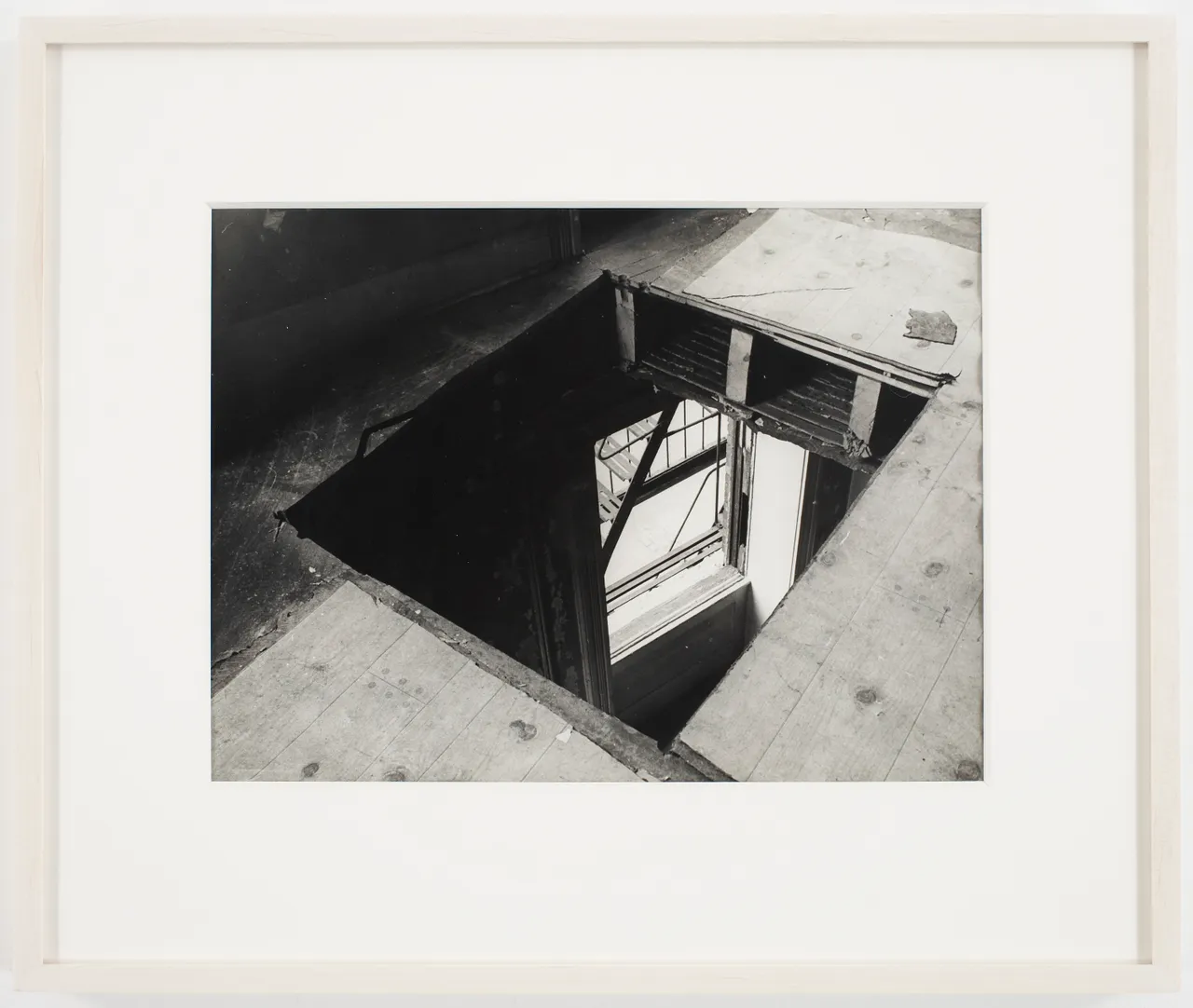

The renovations of that space and 112 Greene Street gave him the idea for what would become known as his “building cuts,” and he soon made his first foray, with trips to abandoned buildings in Brooklyn and the Bronx. He photographed from disorienting angles the odd windows that he opened, and even took cross-sections of the buildings to exhibit at 112 Greene Street, under the title “Bronx Floors.” The remains of wallpaper and molding around his dissections emphasized what the artist said of a later work: “The shadows of the persons who had lived there were still pretty warm.”

Matta-Clark’s reputation remains well preserved for his good will, but the art historian Douglas Crimp, in his recent memoir, points out that the artist’s own “imaginary sites” weren’t always abandoned. Matta-Clark got away with “Day’s End” because police and dockworkers tended to avoid the gay men known to go cruising at the piers, the same men whom Matta-Clark locked out when he took possession of the building. A closer look at a photograph of the FOOD storefront reveals the sign above, painted with the words “Comidas Criollas,” a testament that Matta-Clark’s business was not, in fact, the first restaurant in SoHo.