created, $=dv.current().file.ctime & modified, =this.modified

tags:architecture

Levitt is most famous for building “Levittowns,” developments of thousands of homes built rapidly in the 1940s, ‘50s, and ‘60s. By optimizing the construction process with improvements like standardized products and reverse assembly line techniques, Levitt and Sons was able to complete dozens of homes a day at what it claimed was a far lower cost than its competitors.

instead of homes custom-designed for each buyer, it would build pre-designed homes. It also began to study ways of building more efficiently by steadily building larger numbers of homes.

In 1946, the company began to acquire 7,000 acres of potato farms on Long Island, which became available in part because the “golden nematode” disease was wiping out the potato crop, to build what would be the largest privately-built housing project in American history.

Levitt and Sons broke ground on the first 2,000 houses of this development, originally called “Island Trees,” in the spring of 1947.

standardization:

Building so many homes so quickly — an average rate of around 10 homes per day — required Levitt and Sons to radically streamline the construction process from top to bottom. First and foremost, Levitt and Sons standardized its product, repetitively building the same model over and over again, and updating it over time as tastes changed and the design was improved. It removed extraneous elements and simplified the design: unlike most homes at the time, Levittown homes didn’t have basements, nor did they have porches. Components like exterior walls and roofs were designed to have as simple shapes as possible (no complex hips or wall jogs), and rooms were arranged so that plumbing lines could be placed near each other to simplify pipe routing. Levitt stated that they designed and redesigned one house model more than 30 times, building and tearing it down each time and spending more than $50,000 (over 6 times the value of the house) before being satisfied.

diving labor and specialization:

At Levittown, the construction process was broken down into 26 separate steps, each performed by a separate crew. Crews would go to a house, perform their required task (using material that had been pre-delivered), then move on to the next house. Within the crew, work was further specialized: on the washing machine installation crew, William Levitt noted that “one man did nothing but fix bolts into the floor, another followed to attach the machine,” and so on.

North Shore Supply Company was their own distribution company which prevented against delays.

At its peak Levitt and Sons was completing 36 homes in Levittown a day.

By the 1960s they had completed 60,000 home builds and were the largest home builder in the world.

Land use controls and development restrictions slowed down new home construction later on, also driving up the price of land and the cost of homes.

International Levittowns

while conditions in the U.S. might no longer allow for Levittown-style construction, Levitt thought that places around the world might. Levitt and Sons began construction on a Levittown in Puerto Rico in 1963, ultimately selling more than 10,000 homes on the island. Levitt also started operations in France and Spain, though these never attempted any large-scale, Levittown-style construction.

Bankruptcy in 2008 and a final one in 2018, which shuttered them for good.

William Levitt had failure after failure of aborted projects.

The fortune he had made from the sale of his company to ITT, and the trappings of wealth (his art-filled mansion, his 240 foot yacht) were all gone, and he died in poverty in Long Island in 1994. Up until his death he was still planning new development projects that would herald his turnaround.

Levitt-villes in France

NOTE

Sparked by this knowledge, delving into France

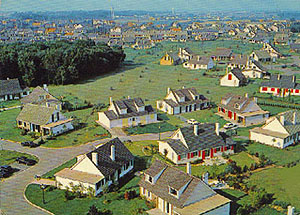

In 1965, William Levitt, America’s largest home builder and creator of the famous Levittowns, constructed a “new village” in the suburbs of Paris. He built 500 houses in Le Mesnil-Saint-Denis, whose mayor wanted to create an alternative to the grands ensembles he hated. It was a huge success and the first of several Levitt-villes en France.

French desire for “This was the case despite the overwhelming desire for detached homes rather than apartments”

Isolation and contact, Berrurier to Levitt:

We don’t want simply to build houses,” Berrurier told the American homebuilder. Our goal is to “create a … community in which people can be happy because they have the ability to alternate between solitude and social contact.

The Levitt homes, the ads maintained, were “real residences in all their nobility. Not housing blocks, but separate domains surrounded by gardens that extend into the forest close by.”

appropriation of space:

By “appropriate,” he meant the ability to shape space according to one’s needs and desires and in a way that gives people a sense of security denied to non-owners.

“When I come home,” said one interviewee, “I cry with joy to be in my own place with all my things.”

dissent:

L’Architecture d’aujourd’hui, a glossy magazine that touted modern design, condemned Levitt’s proposed French houses as “symbols of bad taste, obsolescence, and the complete absence of any architectural qualities.

This kind of dwelling, they said with some justice, divided what had long been farms, forests, and open lands into small chunks of identical private spaces separate from one another and closed to the non-homeowning public.

A more salient – and less dystopian – criticism, though virtually no one made it in the late 1960s and 1970s, would have been that the movement to single-family suburbs would only worsen France’s residential segregation by class and race.

Fanny Taillandier’s - Les États et empires du lotissement grand siècle. Archéologie d’une utopie

The plot unfolds in a distant post-apocalyptic future when fixed residence no longer exist, and nomads roam the Earth. The narrator is a nomad who stumbles on a long abandoned French Levitt community. He or she – we learn virtually nothing about the narrator – notes that although people hadn’t lived there for eons, the dwellings were mostly intact, standing as “identical houses, one after the other, motionless and seductive.”

This Levitt-ville, Taillandier’s narrator says, represents the swan song of the “strange period in human history, which for a few centuries, was sedentary, pacific, and consumerist.” The purpose of this American style lotissement was to grow new roots for an unrooted bourgeoisie, a class freed by cars and phones and televisions to move away from the city and skip from job to job, house to house, discarding obsolete consumer goods along the way